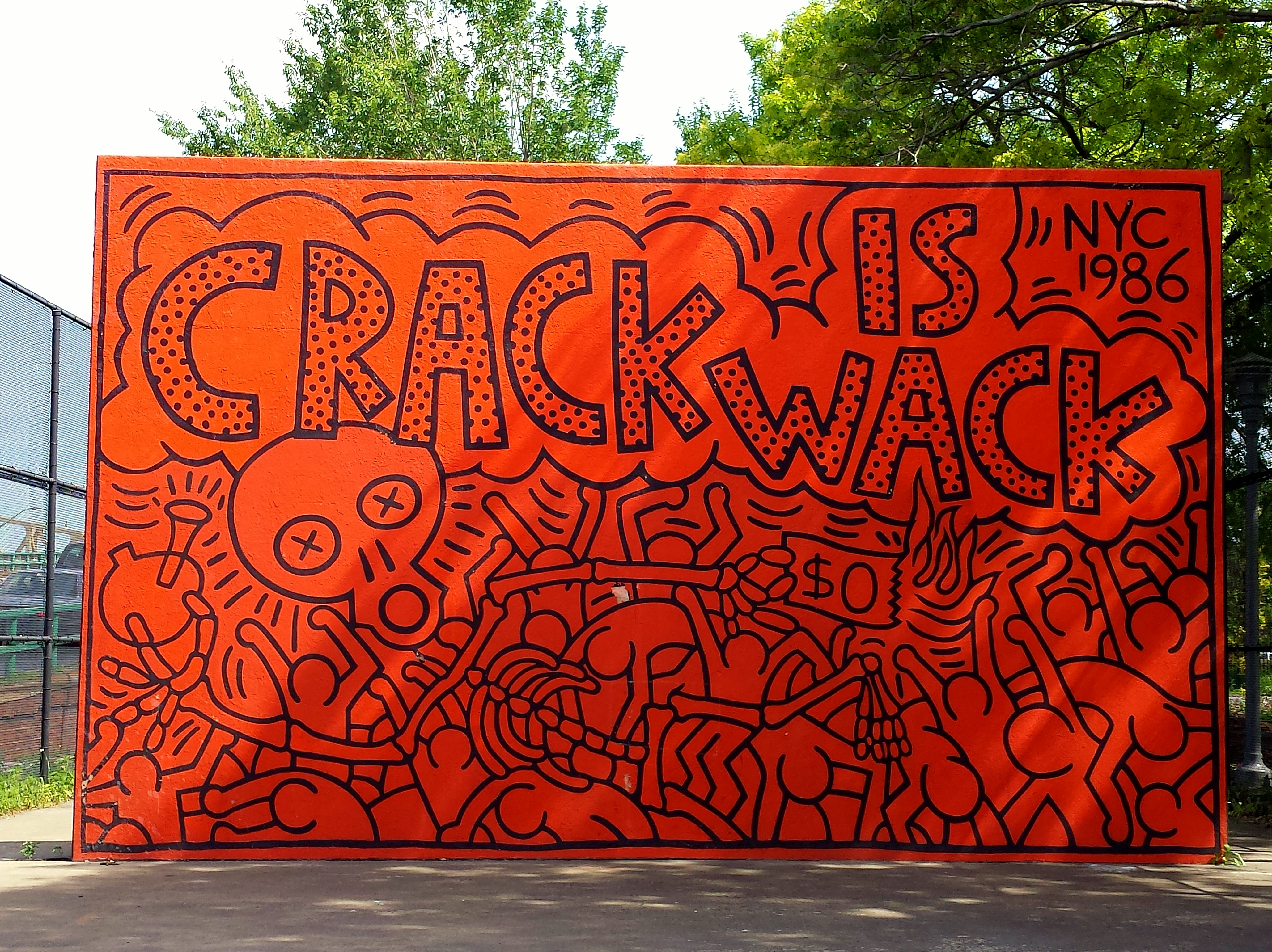

photo courtesy of User gigi_nyc: Flickr

By 2008, 1 in 9 African Americans aged 35 and under were in prison. According to the ACLU, in 2011 roughly 85% of the 12,000 crack offenders in prison were African American. In a 2010 Huffington Post interview, Representative Keith Ellison, a former trial lawyer, talked about the racially based sentencing disparities: “you see the black guys are going to get ten years in prison for having basically the same substance: one is powder [cocaine], one is crack.” Ellison gave his explanation for the disparity, claiming, “Blacks don’t use that much crack but in terms of who gets caught dealing it… [blacks are] disproportionately more likely to be arrested with it…”

In Politifact’s interview with Michael Tonry, a professor of law at the University of Minnesota, Tonry said, “Whites are more likely to sell to people they know, and they much more often sell behind closed doors. Blacks sell to people they don’t know and in public, which makes them vastly easier to arrest.” Drug arrests have been extremely common, with 1,663,582 people arrested in 2009 for nonviolent drug charges according to the Drug Pollicy Institute.

Current conviction statistics reflect the disparity: blacks make up 40% of those convicted of a drug related crime despite only representing 13.2% of the U.S. population. However, according to a 2011 national survey on drug abuse and health, blacks lag behind whites in terms of usage of almost every drug with the notable exception of crack cocaine, where 5% of blacks had used crack in their lifetime and 3.4% of whites had used crack in their lifetime. However, whites were almost twice more likely (17.1% to 9.9%) than blacks to have used cocaine in their lifetime.

These facts, however, were ignored by politicians and policy makers seeking to whip up white political support. Their fear mongering has succeeded, and a series of Republican presidents as well as Bill Clinton have been elected after peddling “tough on crime” policies that harshly punished nonviolent black drug users. The repeated demonization of blacks as criminal drug users persists and is used to block reform of unfair sentencing.

What is powder cocaine, and what is crack cocaine? How are they different, and what are their different effects?

Powder cocaine is a hydrochloride salt derived from the coca plant which can be converted into crack cocaine by mixing it with water and baking soda. The solution is then boiled until it forms a solid mass commonly known as “freebase” because it lacks hydrochloric acid – allowing it to be smoked. This mass is crack cocaine, a smokeable and more addictive version of powder cocaine. Smoking crack results in a far faster metabolization of cocaine into the body, causing a shorter but more intense high. The outcome, a more potent, addictive and dangerous drug which expert panels have studied and consistently agreed is about two times more dangerous than powder cocaine to both the user and society.

In an interview with ATTN, pharmacist Jenni Stein laid out the criminal advantages of crack’s increased potency. According to Stein, cocaine was made more potent “so it could be transported in larger quantities and so people could get more bang for their buck, also noting that“[One] reason we have crack, is because we made cocaine something that’s illegal.” In a Huffington Post interview, Keith Ellison explained political opposition to the Fair Sentencing Act—the bipartisan initiative to reduce the disparity on crack vs. powder cocaine sentencing—commenting, “people who oppose even this mild reform say it’s all to help black people. But the reality is that it’s just that we’ve incarcerated a whole generation of black urban youth.”

How was the “War on Drugs” used to drive a wedge of fear between whites and blacks?

President Richard Nixon, among those who peddled to white fears on crime, created the “war on drugs” in 1971 as a political tool to demonize and defame his political enemies. Among these enemies were deemed anti-war hippies and blacks. During an interview conducted in 1994 by Dan Baum, a writer for Harper’s Magazine, one of Nixon’s top aides John Ehrlichman, infamously commented “We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the [Vietnam] war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin. And then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities,” Ehrlichman said. “We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.” The strict anti-drug policies, including mandatory minimums and no-knock warrants, put in place during Nixon’s administration remained after his resignation, continuing through President Gerald Ford’s term as well as President Jimmy Carter’s term. Ronald Reagan increased punishments for drug possession and utilized the war on drugs as a powerful political tool during his time in office. Between 1984 and 1989 a series of polls conducted jointly by the New York Times and CBS news revealed that drug use had gone from being the number one concern of just two percent of the nation to roughly sixty-four percent of the nation. Years of fear mongering had permeated into the American mainstream

Nancy Reagan’s “just say no” campaign soon became emblematic of the zero-tolerance policies and fearmongering which helped create a 700% rise in convicted non-violent drug offenders from 50,000 in 1980 to over 400,000 by 1997. In a study on white, black and hispanic drug use conducted by NIDA (the National Institute on Drug Abuse) in 1991, 75% of powder cocaine users were white, 15% were black and 10% were hispanic. For crack, whites accounted for the majority, 52%, of reported usage. Blacks made up 38% and hispanics comprised 10% of the group. There was a racial divide in crack vs. powder cocaine usage, but whites still made up the majority of both crack and powder cocaine users. Furthermore, while blacks comprised only 38% of the users of crack cocaine, they made up 79% of the 5,669 people sentenced for crack possession in 1991. The arrest and conviction rates among blacks and whites were disparate and unjust, and the U.S. government did not fix the problem.

The harsh punishment of crack was also related to blacks because of economic and social problems afflicting poorer inner city neighborhoods. These problems, such as poverty and unemployment, were harder to address. In the same 2015 interview by ATTN, pharmacist Jenni Stein revealed that, “Crack was used as a scapegoat for complex social problems — unemployment, poor education, lack of resources, violence, and the list goes on. It was easy to blame drugs for inner-city woes, which made the war on drugs appear to be a necessary and helpful solution.”

In 2010, after the “tough on crime era” began to subside, the disparity between crack and powder cocaine punishments was reduced to 18:1 through the Fair Sentencing Act (FSA) passed with bipartisan support in Congress. 18:1 was nonetheless a compromise, with some human rights groups such as ACLU and FAMM arguing for a 1:1 ratio. The change from 100:1 to 18:1 is also much less of a roll back than it sounds. Possession of 28 grams of crack results in a mandatory five year minimum on a first time possession with intent to distribute; it takes possession of 500 grams of powder cocaine to receive the same sentence. Yet, the FSA was still a step in the right direction. Important statutes of the act included retroactive sentence reductions, which affected roughly 7,700 federal prisoners upon its initial release. According to FAMM, FSA makes roughly 2,000 crack possession sentences fairer each year. The act also abolished mandatory five year minimums on simple crack possession. Simple possession is defined as possession of a controlled substance without intent to distribute. The changes to minimums, however, were not made retroactive. With human rights groups, politicians and pharmacists alike pushing for retroactive reductions to mandatory minimum sentences and a 1:1 ratio, the fight for equality continues.