Nestled between San Francisco’s Sunset and Richmond Districts and stretching from the western hills of the city to the Pacific Ocean, Golden Gate Park includes 1,017 acres of lush greenery, cultural and recreation facilities, hidden gardens, and winding walking paths. The park is located at the heart of the city — a place in constant use by denizens of the City on the Bay — where families enjoy picnics and games, rollerbladers whiz through its streets, and anglers dip their bait into a lake and fish.

How did this precious public park come to be — in a city notorious for competition for its real estate?

In the 1870s, the city of San Francisco decided to allocate a vast tract of land for a public park. The city hired noted surveyor and engineer William Hammond Hall to transform the strip of land now known as the panhandle and the vast expanse of sand dunes, which used to stretch from the inland hills to the ocean, into a beautiful park. This space was gradually transformed and preserved for public use and recreation. By 1879, under Hall, 155,000 trees had been planted. The trees which we now think of as native to Golden Gate Park— the eucalyptus, Monterey pines and Monterey Cyprus — joined the real native species such as oaks.

The park flourished as a recreational haven, a jewel in the city. However, in 1906 it served as a different kind of haven: an emergency refuge. The Great Earthquake and Fire of 1906 left 250,000 San Franciscans instantly homeless. To escape the conflagration in the city, 40,000 people fled to Golden Gate Park. Eventually, in a joint effort, the San Francisco Relief Corporation, the San Francisco Parks Commission and the Army installed a vast grid of tents, later replaced by wooden cabins, in Golden Gate Park to house people displaced by the fires. All this temporary housing was removed from the park by mid-1908.

Today, Golden Gate Park is a place where San Francisco residents and tourists alike gather to enjoy the outdoors. My favorite spaces in Golden Gate Park are its beautiful gardens, specifically three gardens near the 9th Ave and Lincoln entrance to the park — the Botanical Garden, the Shakespeare Garden and The Japanese Tea Garden. The National Aids Memorial Grove, conceived in 1988 and gradually created throughout the 1990s, is also nearby.

If you’re planning to explore these three gardens on foot, you might stop at one of the many eateries and cafes surrounding 9th Avenue and grab a quick snack.

After crossing Lincoln on 9th Avenue, you may be hit with sounds of children screaming excitedly and music pumping out of open car windows. However, a place of discovery and peace — the Botanical Gardens — lies immediately on your left.

When entering the Botanical Gardens, the sounds of the city fade away, getting softer as you walk further into the unique gardens. San Francisco’s Botanical Garden is home to 26 thematic gardens containing plant species that can be grown in San Francisco’s particular climate. Ask for a map at the front and then spend as long as you wish exploring the flora. The gardens are planted to represent different geographical locations, taxonomies and themes. Explore the Cloud Forest of the Andes or delve into the Fragrance Garden. Take a moment to stop and reflect at the Moon Viewing Garden, whose Japanese plant species and stone pagodas provide a sense of tranquility. If you’re traveling with younger explorers, trek through the entire garden to find the Children’s Garden, where you will find homemade musical instruments to play and piles of wood chips perfect for jumping in. By the time you discover this fun-filled garden, though, if you’re with a little adventurer, they may be ready for their afternoon nap — as you will have hiked about half a mile through beautifully treacherous terrain.

The Botanical Gardens is free to members, school groups, residents of San Francisco City and County and to those receiving food stamps. On the second Tuesday of each month, the gardens are free to all. Visiting the gardens is also free between 7:30 a.m. and 9 a.m. This is the time when many bird watchers visit — ready with binoculars and cameras to enjoy the avian residents and visitors. The garden is always free to birds!

After exiting the Botanical Gardens, follow the winding cement paths to discover on your left the charmingly hidden Shakespeare Garden. As you walk down the brick path running through this garden, you will be transported back to old England. As you reach the end of this walkway, you will discover an alluring brick stage and find yourself face-to-face with the (stone) bust of Shakespeare himself. If you feel so inclined, you can even put on an impromptu performance for other visitors! If the performing arts are not for you, this serene garden is the perfect place to enjoy a picnic lunch.

Photo by Charlotte Kane

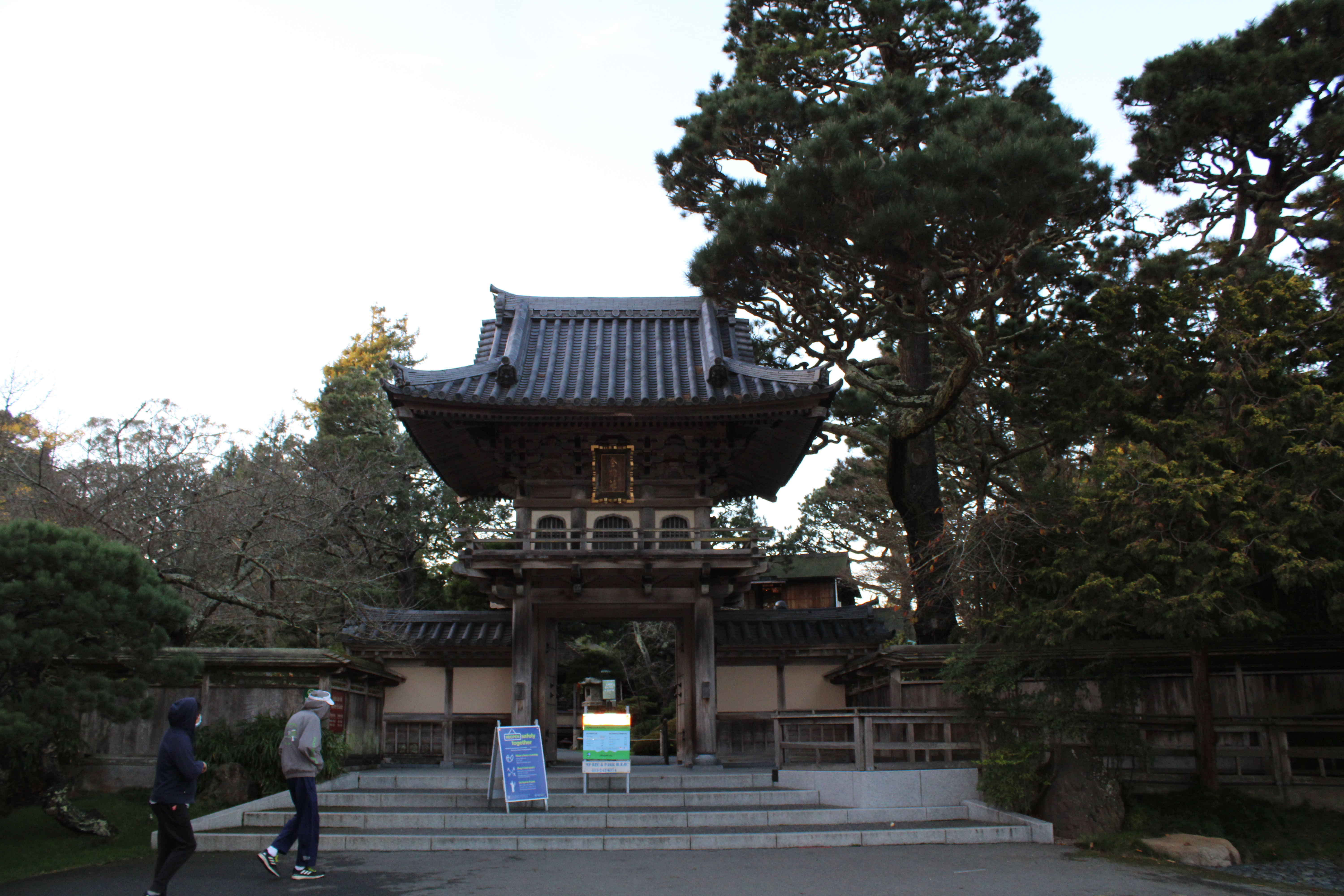

After saying goodbye to Shakespeare’s garden, head over to The Japanese Tea Garden to find a moment of mediation and quiet joy.

The Japanese Tea Garden was created in 1894 as part of the Japanese village at the California Midwinter International Exposition, also known as the World’s Fair. After the fair was over, the Japanese landscape designer Makoto Hagiwara decided to transform the village into a permanent garden. He expanded the original plan for the garden from one acre to five and imported koi and many artifacts. To oversee the gardens, Hagiwara placed his home (a contractual arrangement with the city) in a compound on site. Hagiwara died in 1925. His family continued to live in their house and his daughter oversaw the garden.

Hagiwara had immigrated to San Francisco in 1878, and he became a treasured landscape designer in the Bay Area. Tragically, in 1942, during World War II, the Hagiwara family were turned upon and lost their home. They were imprisoned in a U.S. internment camp. Their home, along with all of the Japanese treasures collected by Hagiwara in the Tea Garden, were destroyed; the tea garden was rebranded “The Oriental Tea Garden.” The garden we now know is the rebuilt Japanese Tea Garden.

While exploring this peaceful garden, make sure to also reflect on its painful history.

Upon entering the Japanese Tea Garden, you’ll find yourself at the base of the arch of its renowned Moon Bridge. As you scale this steep bridge, look down to watch the vibrant ripple of the water beneath you and the reflection of yourself surrounded by verdant greenery. After climbing down the other side of the bridge, wander through the gardens to admire the unique plant species native to Japan.

Photo by Charlotte Kane

End your visit by stopping at the Tea House inside the garden, where you can enjoy a cup of tea, a bowl of miso soup, fresh mochi and fortune cookies. Some credit Hagiwara with inventing the fortune cookie, which he based on the traditional Japanese cookie, the senbei. He added a little vanilla, to appeal to American tastes, and thought of putting the fortune inside. As you sip tea, think about Makota Hagiwara and thank him for his sublime sensibility and the garden he created — as well as for your fortune cookie.

The Tea House is constructed to be an open-air deck, making it the perfect socially distant restaurant to visit.

Admission to the Japanese Tea Garden ranges from $6 for adults who are San Francisco residents and $9 for non-residents to $3 for minors; children under four are free. On Monday, Wednesday and Friday, admission is free for those who enter the gardens before 10:00 a.m.

The most exciting feature of Golden Gate Park is how you will never stop discovering activities to try out and places to visit. I strongly urge everyone to take a stroll through the park in order to discover your personal favorite garden, scenery, and outdoor activity to do. And continue to uncover the rich history behind one of San Francisco’s biggest attractions.