Long before Lick-Wilmerding was the multicultural, empowering school it is today, LWHS was an all-white institution.

Today, LWHS has affinity groups for nearly every core-identifier, maintains a focus on inclusion in the classroom and promises a robust ethnic studies course on the horizon. The ethos of diversity is strong, and it is baked into nearly every part of the school’s curriculum.

Unsurprisingly, though, at the time of the school’s founding, the racial makeup of LWHS’ classes did not reflect the school today.

LWHS was an all-white institution in 1895, the year of the school’s founding. LWHS educated almost exclusively rich, middle- or high-class teens from San Francisco County.

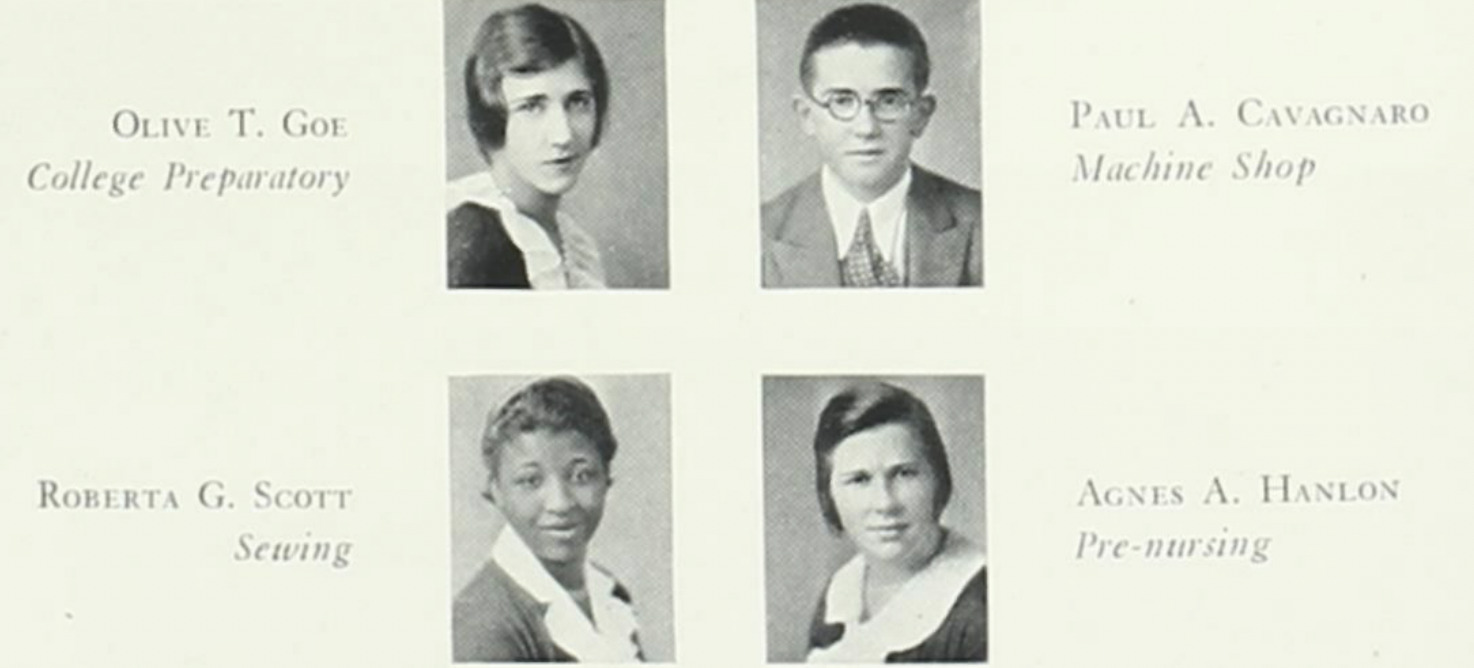

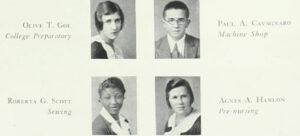

Courtesy of LWHS Archives

It was not until 1931 that the school we now call LWHS became racially integrated. This change is evident in the 1931 yearbook: the first person of color, a Black woman named Roberta G. Scott, is pictured in the graduating class of that year. She was part of the graduating class of Lux School, and she is pictured alongside the rest of her all-white class.

Shortly thereafter, two more students of color appear in LWHS’ yearbooks. In 1932, there were two students of color who graduated. Their names are William C. Yamamoto ’32 and Melfaun H. Pinkey ’32, and according to the 1932 U.S. Census, Yamamoto is a Japanese-American man and Pinkey is a Black woman.

Mohammed Soriano-Bilal ’88, the Director of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Belonging at Stanford University Human Resources, was not surprised when he learned the date of LWHS’ first episode of racial integration. He said, “Globally and in the U.S., the 30s was a time of progressive thinking. Folks were really breaking out of traditional roles.”

Furthermore, he said that the 30s “also coincides with the first big migration of Black folks to the Bay Area, coming from places like Louisiana and Texas. Scott would have been part of that population of folks who were moving to the Bay Area.”

Unfortunately, after the first efforts of racial integration in the early 30s, LWHS experienced a great stagnancy in terms of recruiting people of color. It seemed as if the admissions department at LWHS was satisfied with low representation (but not zero representation) of POC on campus.

From the 30s to the 80s, there were a few students of color at LWHS, but never a critical mass. In the yearbooks from that period — fifty long years of LWHS history — there are far more white students than POC students.

For example, in 1945, fourteen years after LWHS’ first student of color graduated, there were only two students of color in the graduating class. They were both Asian males, Raymond Tom and Benjamin Yip.

In 1955, there were still only two students of color in the graduating class. They were both Black men: Dave H. Russell and Charles J. Suttle. During the time of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to desegregate schools in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), LWHS was resistant to fully embrace the nation’s move towards racial integration. Of course, LWHS was desegregated years before the decision — but, unlike many other institutions in liberal areas, LWHS did not use the decision as a springboard to increase diversity.

A full 44 years after LWHS’ first student of color graduated, there appears to be only three students of color in the graduating class. Eliza Peterson ’75, who appears to be a Latinx woman, Keith Low ’75, an Asian man, and Buddy John Taylor ’75, a Black man.

Nate Lundy ’95, who is Black and Latino, has no trouble reconciling the fact that, for a long stretch of LWHS history, there was a constant but low number of people of color on campus. Lundy is currently the Director of Admissions and Financial Aid at San Francisco University High School. He previously worked as an admissions officer at LWHS, and before that, in the mid-90s, he was a student.

Speaking to independent schools’ lack of diversity, Lundy said that independent schools were created originally to serve the elite: “The reason that they were started was to avoid integration, so it makes total sense that (LWHS) was not a diverse community.”

Starting in the 80s, however, recruitment efforts increased dramatically. Suddenly, students of color began showing up on campus in large numbers. These students would change the fabric of LWHS.

Soriano-Bilal can see why. He said, “Part of the desire to recruit more students of color, specifically Black and brown students, was a competitive push for diversity in the 80s.”

“Lick knew that to remain competitive, they had to bring diversity into the school,” he said. “They made a concerted effort — super intentional — to recruit these students, which they hadn’t done in the past.”

This push for diversity did not just take place at LWHS, Soriano-Bilal said. Independent schools across the country “all of a sudden got very aggressive about recruiting students of color in the 80s.”

Soriano-Bilal’s Class of ’88 saw this first-hand. His class was advertised to the LWHS community as the largest class of Black men that the school had ever admitted. There were six. The Class of ’88 marked a turning point in LWHS history — for the first time, LWHS was taking efforts to create and display diversity.

Along with Black students like Soriano-Bilal, according to him, there was a “meaningful number of students” from Asian and Latinx backgrounds as well.

Efforts to increase diversity, however, were not exactly in good faith. As Soriano-Bilal mentioned, LWHS faced pressure to diversify the school from funders and parents. Furthermore, the students of color in the Class of ’88 felt that they were celebrated so much by LWHS that they were tokenized and reduced to just ambassadors of their race.

The mid-80s marked the beginning of LWHS’ true racial integration. Yes, LWHS had students of color in the past, but never before were efforts made to recruit them specifically.

Lundy’s Class of ’95 had far more students of color than Soriano-Bilal’s Class of ’88. Lundy estimated that, when he was a student at LWHS, students of color comprised about 30% of LWHS’s total student population.

Racial diversity among the faculty at LWHS noticeably lagged behind racial diversity among the student body. According to Chris Yin, a teacher of color at LWHS since 1995, even though LWHS was the “most racially diverse high school in the Bay Area” when she arrived, there was an insufficient number of teachers and administrators of color on campus. In fact, she said, “When I arrived here at Lick, there might have been five other BIPOC faculty on campus.”

Yin mentioned that when she was promoted to ninth- and tenth-grade dean in 2000, she “believes she was the first BIPOC admin” ever at LWHS.

Ana Vasudeo ‘00 observed the lack of diversity among LWHS teachers. She, a Latina, said that even in the Spanish department, there were no Latinx teachers. The nearly all-white faculty at LWHS fostered “a disconnect on how to support kids of color. We had great allies in the faculty, but were missing having teachers that looked like us and came from similar backgrounds,” according to Vasudeo.

For example, Vasudeo told of the time that she struggled in a web design class because of her lack of a home computer. Vasudeo said that her teacher assumed she was slacking off in the class: “The teacher thought I wasn’t trying, and he never realized that because I was low-income, I didn’t have access to a computer. That (class) was my first time seeing a computer,” she said.

However, according to Vasudeo, there were some teachers at LWHS who were surprisingly receptive to low-income students. “One time (for homework) I was supposed to do an assignment on a computer. And I had to tell my teacher that I don’t have a computer, and he then got me my first computer. He donated my laptop to me.” Vasudeo mentioned that this teacher’s name is Bruce Cohen. “I think there are people like Mr. Cohen, who had a big heart, but my web class teacher never thought that maybe kids of color and low-income kids struggled in that class,” she said.

These growing sentiments of inclusion were caused by a growing presence of students of color. And this growing diversity was spearheaded by people like Lundy, an admissions assistant during the mid-2000s. Lundy and his coworkers worked to advertise LWHS to more students of color and admit them into the school

Soriano-Bilal finds Lundy’s efforts to be instrumental in diversifying the school. Soriano-Bilal said that Lundy was the first to “decide to recruit students from every county that BART touched to Lick-Wilmerding.”

This process, Soriano-Bilal believes, tremendously diversified the school because it allowed LWHS to recruit students from all across the Bay Area: “The reason that Lick is so diverse today is because Nate (Lundy) set up that infrastructure,” Soriano-Bilal said.

These recruitment efforts are really at the heart of LWHS racial integration story. Without the specific recruitment of eighth graders from communities around the Bay Area, not necessarily just within San Francisco, LWHS would probably never have transformed its racial and cultural makeup beyond its all-white roots.

Discussing his ethos for recruiting kids from across the Bay Area, Lundy explained that LWHS has a “tactical advantage” compared to other independent high schools: it is right on the BART line. “No matter where the middle school is, if it’s on the BART line they can get to us,” Lundy said.

He was motivated to recruit kids of color because of his own experiences as an East Bay student of color at LWHS. Lundy said that he appreciated the great education that LWHS gave him, but he had trouble relating to other classmates who lived in the city and drove to school.

“There were very few folks that were doing what I was doing, that could share my experience,” he said.

When Lundy began working (as an admission officer), he wanted to recruit East Bay kids, and especially East Bay kids of color, at a higher rate than they were traditionally recruited. “When I started working as an admissions officer, I immediately wanted to recruit more kids like me, and I wanted more kids to be here so that kids didn’t feel isolated, didn’t feel alone in their own experience.”

Lundy’s efforts to recruit kids from all across the Bay Area are critical to the change of LWHS’ racial makeup. The history of the affinity spaces at LWHS, one aspect of the resources available to kids of color, provides a valuable framework to observe this change. After all, traditionally, racial affinity spaces have only come about on school campuses when there was a critical mass of students of color.

When Soriano-Bilal was a student at LWHS in the mid-80s, there was no such thing as affinity spaces. He explained that, in fact, there was no infrastructure at all.

During his student tenure, Soriano-Bilal said that he faced a number of racist comments at LWHS, from teachers and students alike. And when not being verbally attacked, Soriano-Bilal said that his classmates still treated him differently than they treated the white students.

“I felt like I was seen as a commodity — as a sort of curiosity — rather than as an equal, or even as a human being,” he said. But, because there was no Black affinity space at the time, Soriano-Bilal had no structured environment to communicate about these issues.

Lundy’s Class of ’95 saw one of LWHS’ first affinity spaces. It began before his class came to LWHS and it was hugely important to students of color during the time. The space was initially called the Minority Student Union, but it changed to the Multicultural Alliance (MCA) during Lundy’s student tenure. Lundy explained that, during his time, there were not enough students of color to warrant the production of affinity spaces for each core identifier.

“From my student perspective, we had each other. And it was great! I don’t think we even knew that there was this possibility to have individual affinity spaces.”

“I wasn’t actively missing an (individualized) space when we were all together in the Multicultural Alliance. It was awesome. It was family,” he said.

Yin witnessed the blossoming of individualized affinity spaces at LWHS. When she first came to LWHS, there was only the MCA: “When the MCA started off, it was very much a place where people were sharing the traumatic things that were happening to them in classrooms,” she said.

The only affinity space on campus, the MCA served an important purpose for students of color. As Yin mentioned, though, it was a mixed affinity space because “we had folks that were Black students, Latinx students, Asian students and white students in the MCA.

According to Yin, there was a club for AAPI students during her early career that coincided with the MCA. However, she did not consider this club a robust affinity space because “they kind of just got together and ate.” Seeing the growing Asian student body on campus — and being an Asian teacher herself — Yin decided to transform the club into the empowering affinity space it is today.

“I really wanted to create something that actually talked about the issues of being Asian-American,” Yin said.

Teaming up with an Asian-American student named Debby Soo ’99, Yin was the first teacher to sponsor ASIA, the Asian-American student affinity space.

Vasudeo, who started Latinx Unidos, LWHS’ affinity space for Latinx people, said that an increase in anti-Latinx discrimination motivated her to start the affinity space.

For example, she both noted Proposition 227, which attempted to abolish non-English education in California schools, and Proposition 209, which attempted to get rid of affirmative action practices. Seeing racist laws like these being discussed in the California government, Vasudeo felt that she “wanted a forum where everyone could discuss what was happening in California that was impacting the Latinx community and then do something about it.”

And, indeed, Latinx Unidos became an active affinity space, one which often took steps to solve the problems it was aligned against. Vasudeo mentioned how, in opposition to Proposition 227 and 209, Latinx Unidos would bus over to Spanish-speaking communities that were at risk of being marginalized by an English-only education, and they would tutor students in their language: “Going to volunteer at Mission schools and helping kids that were English language learners was a way to give back and use our skills as kids that spoke Spanish fluently.”

Lundy also started an affinity space — AIF, or Ad Ingenium Faciendum (towards the building of character). AIF is an affinity space for boys of color at LWHS, and it was started in 2010 when Lundy was an admissions counselor. Similar to other affinity founders at LWHS, Lundy was motivated to start his affinity space because of racism targeted against people who shared his core identifiers.

“There was a point where we had a significant group of Black and brown boys on campus, and they weren’t thriving in the way that I was watching the other groups on campus thrive,” he said. “And, in fact, some were being dismissed and asked to leave. I got together with Christy Godinez, from the Center, and we talked about ideas to support them… And so I founded AIF, a group for boys of color.”

Above all, Lundy said, he wished that founding AIF allowed Black and brown kids at LWHS to realize that “they have no reason to feel like a guest in their own school.”

Since Roberta G. Scott’s Class of ’31 — the first class that was racially integrated — it is clear that LWHS has come a long way. Racial diversity and awareness have become a central tenant to the school, and its presence in every part of student life is undeniable. This process towards a greater appreciation for diversity, though, is frustrating to recount. For decades after the first racially integrated class, there was no push whatsoever for greater POC representation.

Through the determined efforts of people of color, however, students and teachers from all walks of life joined the community.

The future of diversity at LWHS looks bright. According to Yin, “Right now, we have as much BIPOC representation as we’ve ever had.”

In addition to increasing the sheer number of students of color on campus, Yin said that LWHS has attempted to “shift the culture” so that it is more welcoming to students of color. These efforts, including LWHS coursework, class meetings and professional development, have certainly made an impact on the community.

In the future, hopefully, LWHS will continue on this path toward diversity and become a place where all students can express and celebrate their true selves.