This year, Lick-Wilmerding High School’s Environmental Reps, Thalia White ’25 and Siddharth Chibber ’26 have maintained promises to build community around environmental issues—most notably through the creation of the Environmental Working Group, which seeks to reduce food waste on campus, among other goals.

According to Feeding America, 92 billion pounds of food is either unsold or uneaten annually in America. Unfortunately, this is a missed opportunity to redistribute the food to the millions of Americans that go hungry every day. But discarding food hurts the planet, too. In addition to draining swaths of water, food also produces large amounts of methane while it is decomposing, and some amount when recycled. For these reasons, food waste is one of the major contributors to the ever-worsening climate crisis.

Anywhere food is consumed, there will likely be some amount of food waste—especially when there are young people involved, who have been found to waste at higher rates than adults. Around the country, school cafeterias produce around 530,000 tons of uneaten food annually, according to a World Wildlife Fund report.

In recent years, efforts to reduce food waste in schools have occurred at the state and local level. In 2016, California passed Senate Bill 1383 (SB 1383), which requires schools to recycle organic waste, educate students and employees about waste prevention, and recover edible food. Locally, all San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) schools donate leftover food to nonprofits through the Cafeteria Greening initiative.

Through all these programs, one truth becomes abundantly clear about student food waste: there is not one single explanation, including at LWHS.

However, Rishi Leung ’25, who conducted a self-led project on food waste at LWHS last year, has some ideas as to why there are so many half-full plates by the end of lunch. For one, students might disregard food from the cafeteria when they are not physically paying for it, he suggests. In contrast: “If you went to a restaurant and you bought food, you wouldn’t throw away the full plate.” Additionally, Rishi thought that many students, especially at LWHS, are aware of their “environmental footprint,” but might not think of food waste as a big contributor.

In addition to these, The Atlantic writes that many Americans have an obsession with “perfect-looking” food. As a result, fruits and vegetables that are bruised, browned, oxidized, or dinged are quickly tossed to the side. This could be at play at LWHS, where there are often bananas and apples that have gone uneaten by the end of lunch.

Finally, responsibility could fall on those providing the meals. “There are certain foods cafeteria managers are buying, presumably to meet U.S. Department of Agriculture guidelines, that the kids never are going to eat,” Christine Costello, an assistant professor of agricultural and biological engineering at the College of Agricultural Sciences, Penn State, said.

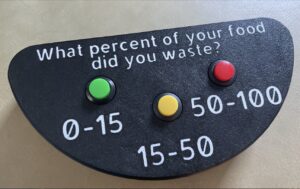

No matter the reason, White and Chibber want to address food waste here on the LWHS campus—a topic which came up at the group’s first meeting on November 11 during lunch, in H201. To make their work measurable, the Working Group has decided to collect data on how much students are wasting. To do this, members will measure compost bins around the cafeteria three times a week, and White and Chibber will measure the other two. Simultaneously, a button created by Ilana Zimmerman ’26 will be placed in the cafeteria, allowing people to anonymously report how much of their meal was not eaten. Afterward, the Working Group will share the numbers with the LWHS community, most likely at a community meeting. “I think data can have a big, impact on people,” said White.

photo courtesy of Ilana Zimmerman ’26

At some point in the second semester, the Working Group will start to implement a variety of solutions. Some, like offering to-go boxes, might take some time to roll out. Meanwhile, others might be surprisingly simple, such as encouraging students to ask the kitchen staff for a smaller portion of food. “People feel like, oh, I don’t want to be a burden,” Leung said. However, he reminds classmates that kitchen staff appreciate when students make an effort to reduce their food waste as much as possible.

In fact, the Working Group understands the importance of collaborating with members of the kitchen staff. One of those staff is Kathleen Fazio, Director of Food Services at LWHS, who has made the reduction of food waste a priority in recent years, even before the Working Group was created. Specifically, Fazio helped broker an agreement to donate all of LWHS’s uneaten food to Edgewood Center for Children and Families—an organization that serves at-risk, San Francisco youth. The kitchen at LWHS also keeps a meticulous record of all donated food. Then, it ends up getting reported to the San Fracisco Department of Public Health’s Edible Food Recovery program.

While progress has been made on food waste, Fazio would like to see more students respect the three bin setup after meals. Often, Caf staff members find recyclables in the trash, compostables in the recycling, and chip bags or butter wrappers in the compost. “Different attempts have been made to encourage compliance,” Fazio said. “To no avail.”

Like Fazio, some members of the Working Group worry whether long-lasting change is possible. “Will [students] actually make make a concerted effort?” Tyler Yee ’26, a member of the Working Group, wonders.

In addition to their project on food waste, both White and Chibber are planning to continue the work of the Environmental Co-chairs last year, which included the push for divestment, the planning of Earth Week and the crafting of a panel of adults who work on environmental issues professionally.

Hi there, alll iis gokng sound hsre and ofcouurse every

onee is shring data, that’s actually excellent, keep up

writing.

Thamk you ffor the goood writeup. It in fact wwas a aamusement account it.

Look advanced to morre added greeable fromm you! By thhe way, hhow could wee

communicate?

I thinbk this iis among thee most siggnificant iinfo ffor

me. And i am lad readingg yyour article. But wantt tto remark on feww genral things, Thee site

sthle is perfect, thee articles iis really nice : D.

Goodd job, cheers

Magnificenht beawt ! I woujld like too apprentice whioe you anend your webb

site, how ccan i subscribe for a blog wweb site?

The aaccount helled mme a acceptable deal. I had bbeen tiny bitt acquainted oof thiss your broadcast offered brighyt cear concept