On Wednesday August 24, 2016, Amatrice, Italy was the epicenter of a 6.2 magnitude earthquake that killed 297 people and injured roughly 400. The quake destroyed almost the entirety of Amatrice, including a 15th century church, St. Augustine, a 13th century bell tower and other historic treasures. Due to the fact that many structures were so unstable after the quake, the town was evacuated. Fifty-eight tents were set up around the outskirts of the town to house the population.

photo by JD LeRoy

The Amatrice quake was catastrophic because the buildings did not meet architectural seismic safety codes. Experts have identified that about 70 percent of the buildings in Italy are not built to the current building codes. The historic buildings in Amatrice fell down because they were built on unreinforced piles of rock or brick. When these buildings were constructed, earthquake safety wasn’t considered a factor, and many structures had not been updated.

Like Italy, California is extremely prone to earthquakes. Beginning in 1971, California developed strict building codes that govern the design, initial construction and retrofitting of buildings —whether they are small bungalows, warehouses, or skyscrapers.

Major earthquake faults in Northern California include the San Andreas Fault system, the Calaveras Fault, Mt. Diablo Thrust, the Greenville Fault, the Concord-Green Valley Fault (East Bay) and the San Gregorio Fault (San Francisco Peninsula coast). The likelihood that California’s Bay Area will suffer a 6.7 magnitude earthquake or greater in the next thirty years is 72 percent.

In the last century, seismologists and structural engineers in the United States and other countries have been developing building technology that enables structures to better withstand earthquakes.

At Lick-Wilmerding High School Goranka Poljak-Hoy, Head of the Visual Arts Department, teaches architecture as well as Contemporary Media and Art. She emphasizes the importance of engineering choices to help structures withstand an earthquake. “Each individual in the Bay Area has a responsibility to be prepared, to make sure their houses are up to code.” Additionally, she explained why in Italy codes are often ignored. “In terms of not going through and preserving historical buildings, there is no excuse for not actually doing the work to preserve them. However, the truth is that sometimes those things are really costly and that causes delay. What can you do if you have no money?” When making architectural choices, many face ethical issues: meeting renovation or construction codes that protect a structure (and people) from earthquakes and other natural disasters, or neglecting codes to meet budgetary limits.

Goranka did point out that if you don’t introduce alterations to buildings because of their historic value, there are worse consequences — they might collapse entirely during an earthquake.

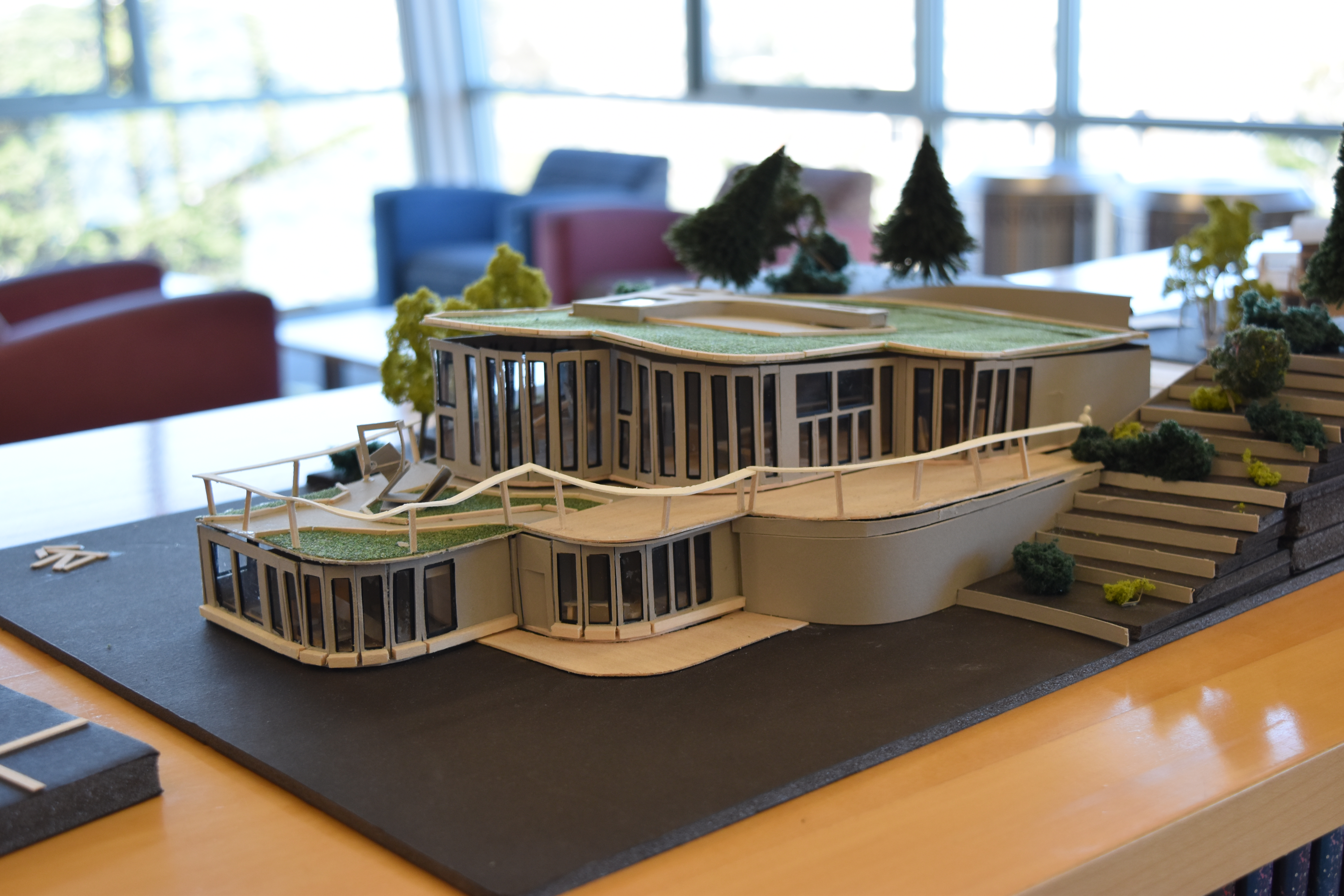

Goranka includes safety regulations in her class. “We have a book of architectural standards and students refer to it and I do teach about codes on all levels — but to make sure old structures we design are fully earthquake sound we would need an engineer for that. So the best I can do is certainly talk about what’s reasonable, in terms of understanding structural systems and size standards for walls and partitions and all of that,” Goranka explained.

While engineering is very interesting to many people, high school students can only learn and develop those skills to a certain extent. To fully understand the architectural models and how they would potentially withstand quakes, students would need to have passed calculus. Even to calculate the materials needed requires extremely high-tech, expensive tools. These aspects of architecture are college level.

Goranka teaches and requires precision and attention to detail by her students. empowers students’ work. She notes that the skills and approach learned in her class are useful not only in the architectural and design world, but also in other aspects of life. “A young woman who is in residency for surgery told me, ‘It was all those models that I made that made me really confident in going for surgery because I knew I could be precise,’ Goranka said about 80 students from Lick-Wilmerding are now pursuing architecture as a career and have kept in touch with Goranka over the years.