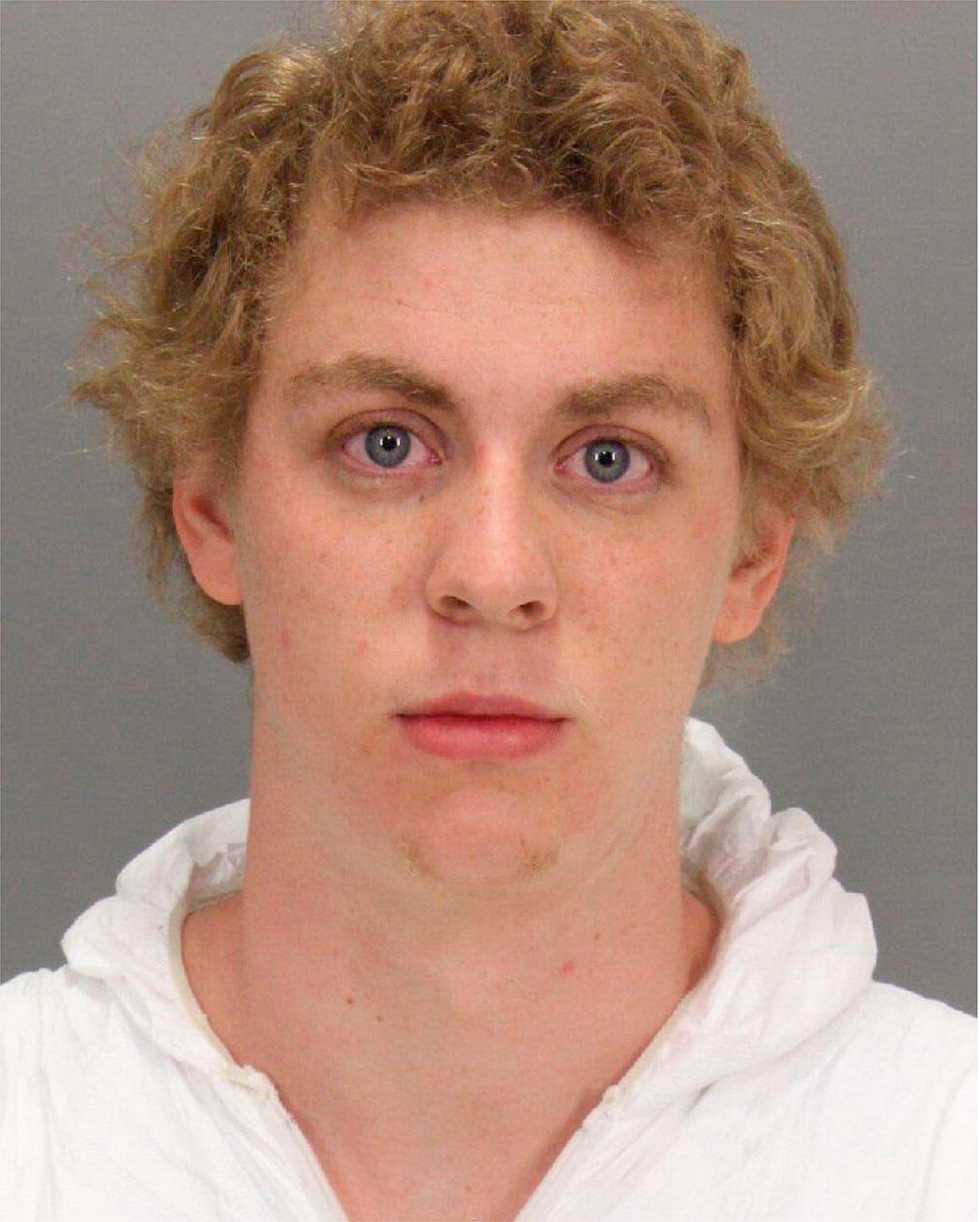

On March 30, 2016, over a year after Turner was caught forcing himself on an unconscious woman behind the dumpster of a fraternity house, Turner was sentenced by Judge Aaron Persky to six months in county jail (of which Turner served only three). The law at the time mandated a minimum of six years in state prison for sexual assault involving force, which was the sentence requested by the prosecution in Turner’s case. At the time there was no law mandating prison time for assault involving intoxication. Judge Persky defended his decision in the face of criticism, citing the ex-Stanford student’s age and clean record and adding that he did not think Turner was a danger to others.

Protesters throughout the country were infuriated by this decision, demanding that Turner’s race, sex, and privilege played a role in his lenient sentence. One petition, which gained almost 200,000 signatures within a matter of days, claimed Turner’s punishment, or lack thereof, “failed to send the message that sexual assault is against the law regardless of social class, race, gender or other factors.”

The claims of protesters were not unfounded. Judge Persky, a white, highly educated male, had negotiated the plea deal in a strikingly similar case. Raul Ramirez, who, like Turner, had a clean record, was a college student who sexually assaulted his female roommate. He was given three years in state prison. Unlike Turner, however, Ramirez was an El Salvadorean immigrant. The sentences in similar cases have been brought forward in light of Turner’s, highlighting the differences between sentences given to white students and students who identify as people of color.

But this case has further implications than the inherent racial prejudices that skew the treatment of non-whites in the judicial system. The role of alcohol in the assault and in the arguments in Turner’s defense highlights the gaps in legislation that influence legal decisions when either the perpetrator or the victim is under the influence of alcohol.

An expert witness for the defense claimed that during a “blackout” state of intoxication, one can engage in activities, including knowingly consenting, but simply not form memories of these events. Therefore, the defense argued, consent during such a state of amnesia should be admissible in a court of law.

Advocates for victims of rape argue that it is this mindset that perpetuates “rape culture” by disregarding rape victims based on their state of inebriation.

While the defense argued that the victim must be held accountable for consenting under the influence, Turner himself claimed that it was his own intoxication that perpetuated the events, shifting blame to the party “hookup” culture. The defense presented multiple character witnesses for Turner, claiming he was not a rapist but a young man with a lot of potential who merely made a mistake.

However, the prosecution noted that none of the witnesses could speak to Turner’s intoxicated state, and while he may not be the “typical rapist,” he was the “quintessential face of campus rape.” People were not happy with Turner’s attempt to avoid blame. “Does alcohol and the idea of ‘hookup culture’ make it easier for things like this to happen? Probably.” A Stanford student noted of the situation, “but Brock Turner didn’t take some magical alcoholic potion and suddenly turn into a devil-horned rapist. The blame can’t be shifted from him like that.”