Depending on who you ask, the individual right to bear arms may date back to as long ago as 872 A.D., or as recently as 2008.

The history of the Second Amendment, which many say protects the right of Americans to keep and use guns, exemplifies a fundamental question of constitutional law: how does the Constitution adapt to changing times?

The amendment guarantees that “a well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” Proponents and opponents of widespread gun ownership debate whether that sentence protects individual or collective self-defense.

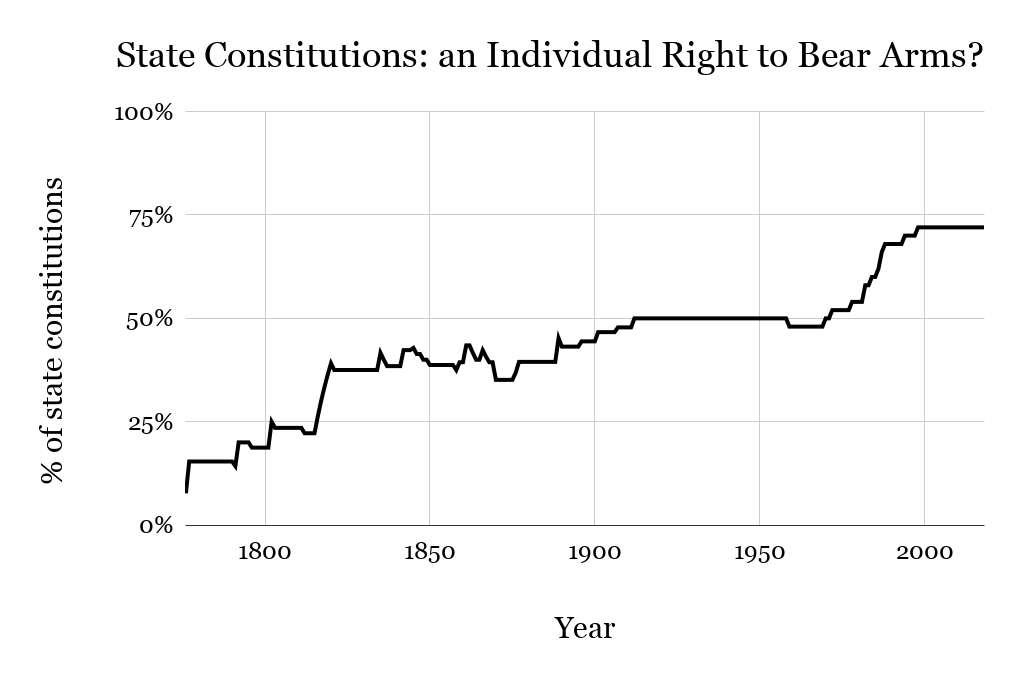

graph by Tuvya Bergson-Michelson, based on state constitutions

Originalists, a group of legal scholars who interpret the Constitution by analyzing its writers’ intentions, can trace the origin of the right to bear arms back a millennium into English law. King Alfred, who ruled in the late 9th century, commanded serfs and nobles alike to own weapons so that they could defend their country in the case of a national emergency. By 1689, the English Bill of Rights listed owning arms for self-defense alongside rights like free elections and due process. An originalist interpretation of the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution not only sees the two uses for weapons as interconnected, but argues that both are integral to the meaning of the amendment.

The response of Professor George Mocsary, an author of a landmark casebook on firearms law, typifies that frame of mind. To him, any discussion of the Second Amendment should acknowledge that “the founders didn’t have the same distinction between individual self-defense and defense against tyranny that we have now” when they wrote it. Thus, both are protected.

In the century following the passage of the Bill of Rights, judicial interpretations of the Second Amendment focused on states’ rights, not gun ownership. The hot legal debate during Reconstruction was whether rights protected in the federal Constitution must also be respected by state and local governments. In United States v. Cruikshank in 1875, the Supreme Court ruled that the Second Amendment “has no other effect than to restrict the powers of the national government.” Furthermore, the court suggested that people targeted by violence (Cruikshank was a member of the Klu Klux Klan) should “look for their protection” themselves, presumably by keeping firearms.

Another case from the era, called Presser v. Illinois, further complicated the picture by tying national defense to an individual’s right to bear arms. The court said that since “all citizens capable of bearing arms constitute the reserved military force of the national government,” strict state gun laws “deprive the United States of their rightful resource for maintaining the public security.” While Cruikshank encouraged the people to defend themselves under the Second Amendment, Presser argued that the people were also vital to the nation’s self-defense.

By the early 20th century, the Second Amendment was an afterthought in constitutional law. Ignored in law schools and history classrooms, the predominant view was that its relevance ended with militias. Much of the reason was legislative — Congress passed very few laws regulating gun ownership or use in the century after Reconstruction. The only prominent challenge to a gun control law, Miller v. United States in 1939, failed when the Supreme Court ruled that a sawed-off shotgun was irrelevant to use for a militia. Gun use was still prevalent, especially in rural areas, but it largely wasn’t a political concern.

The Gun Control Act of 1968, among many provisions, prevented stores from selling firearms without a federal license. Americans accustomed to easy, casual access to guns saw pistols and rifles disappear from the shelves of local stores due to the new regulations.

The resulting shock served as a catalyst for many gun owners, transforming the National Rifle Association (NRA). At an annual members’ meeting in Cincinnati in 1977, NRA membership voted to fire the organization’s leaders, who had supported the Gun Control Act, and enshrine the Second Amendment in the NRA bylaws.

Their new leaders understood the amendment differently from legal scholars of the time. To Marion Hammer, a former NRA president, “Congress decided to take away the rights of free men and women” when they limited access to guns. The “Revolt in Cincinnati” created the modern NRA, funneling money towards its lobbying branch (the NRA-ILA) and shifting the organization’s focus from the sport of shooting to the Second Amendment.

The NRA has been particularly successful at changing

state gun laws. Between 1980 and 2000 the NRA convinced 11 states to amend their constitutions to protect an individual right to bear arms.

Current Lick-Wilmerding students were already in elementary school when the Supreme Court adopted the NRA’s view.

“It is not the role of this Court to pronounce the Second Amendment extinct,” Justice Antonin Scalia wrote in his 2008 majority opinion on Heller v. District of Columbia. The landmark ruling overturned Washington D.C.’s handgun ban. Scalia stated that although gun violence posed a real public health issue, “constitutional rights necessarily take certain policy choices off the table. These include the absolute prohibition of handguns held and used for self- defense in the home.” His opinion refuted practically every argument that the Second Amendment did not protect an individual right to self-defense. The case made little immediate impact — most states already had laws guaranteeing the same thing, due to the NRA’s efforts — but it marked a dramatic shift in Supreme Court precedent. In the past, its decisions had been relatively limited. Never before had the court loudly proclaimed so wide-ranging an opinion on the Second Amendment.

In McDonald v. City of Chicago, two years later, the Supreme Court overturned the precedent of Cruikshank, ruling that state and municipal laws also must abide by the Second Amendment. (Since Washington D.C. is not in any state, its laws technically fall more under federal jurisdiction than those of, say, San Francisco).

The decision also reflected how much public opinion had changed since 1968. “The court often only takes cases once there’s a critical mass of thought,” says Professor Mocsary. Gallup, a major polling agency, has tracked opinions on gun control since 1959. When they began polling, 60% of respondents supported a handgun ban. Now, only 28% do.

Even Heller left space for some gun control. Scalia’s opinion noted that “the Second Amendment does not protect those weapons not typically possessed by law-abiding citizens for lawful purposes,” like short- barreled shotguns and machine guns. Many proponents of gun control would like to see this argument taken further, pointing out the difference between the muskets available to the writers of the Second Amendment and semi-automatic weapons in stores today, like the AR-15, which Nikolas Cruz used in Parkland.

Not so fast, says Professor Mocsary. “The semi-automatic weapon is the quintessential self-defense weapon.” Staples v. United States in 1994 ruled that owning an AR-15 is an “innocent act,” different from owning its illegal military equivalent, an M-16, because so many millions of Americans own the former. Furthermore, “a population armed with bolt-action rifles isn’t a balance against governmental power, but one armed with semi- automatic weapons is,” Mocsary adds. A modern-day militia would need semi-automatic firearms to be effective.

At its heart, the story of the Second Amendment is one of the Constitution itself — of a struggle to apply 18th-century language to 21st-century life. A Constitution is “supposed to enshrine certain values that are hard to change,” Mocsary points out. “It’s not acceptable to say that the meaning of the right is completely different based on what we think today.” Indeed, many of the values of the Founders are still deeply relevant, and the continuity in America’s Constitution is nearly unparalleled worldwide. Opponents of originalism are more inclined to agree with Professor David Strauss, who counters that “there’s no realistic alternative to a living Constitution.” Times change, and “sometimes the past is not a storehouse of wisdom.” In fact, in many ways, the Constitution’s ability to change has given gun owners new protections within the last decade.

Reasonable minds can, and do, disagree on the meaning of the Second Amendment, and on whether the foundation of our government should shift easily. Despite the weight of the storied, checkered history of the Second Amendment, as David Cole says in his book Engines of Liberty, public opinion has been “nonetheless central to the process of constitutional change.”