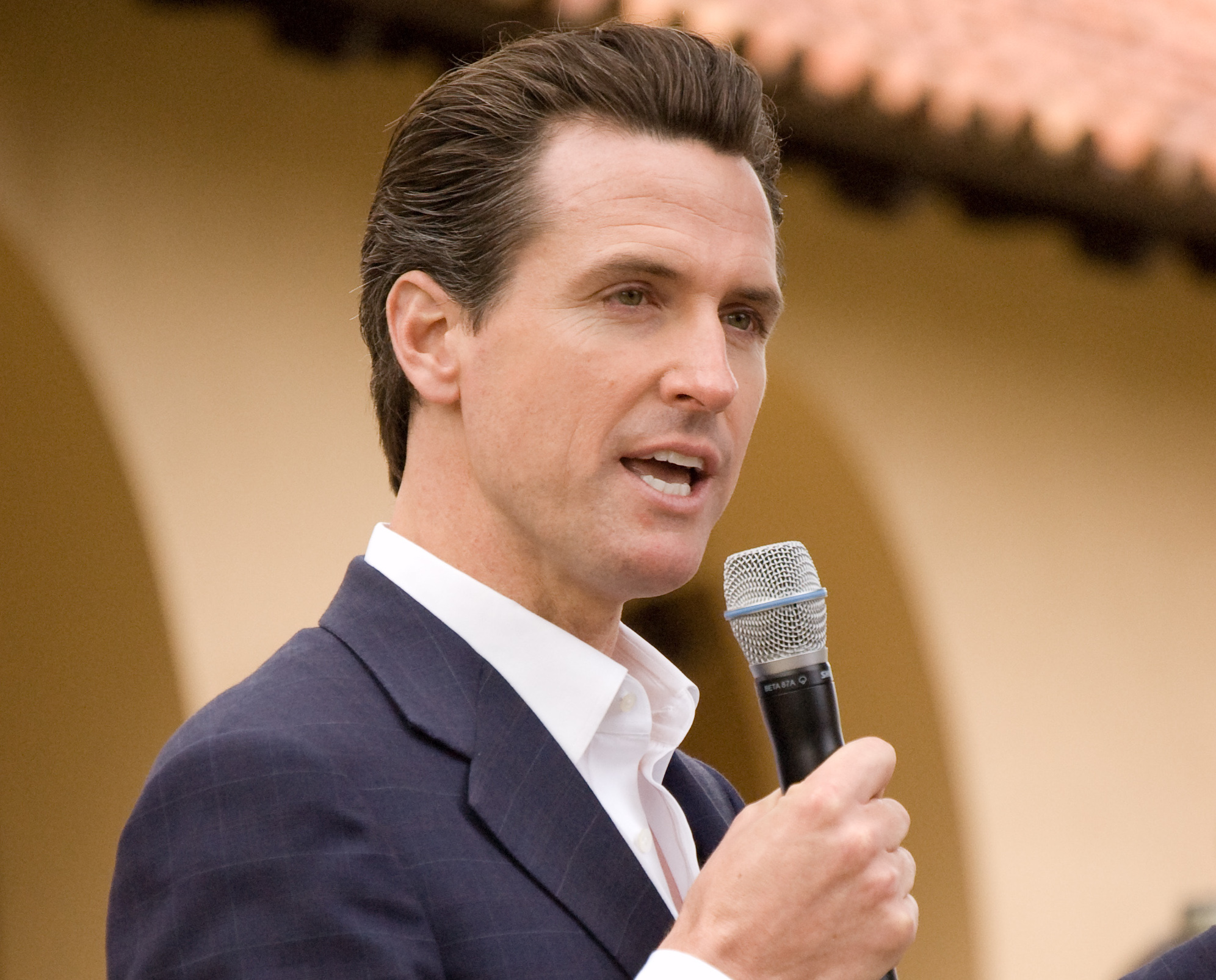

On January 7, Gavin Newsom gave his inaugural address from the steps of the California State Capitol. Newsom — who had been sworn in as California’s 40th governor just minutes before — described his vision for the next era of California politics. Newsom referenced a proverb that he grew to understand during his time as San Francisco’s mayor: “If you want to go fast, go alone; but if you want to go far, go together.”

As the mayor of San Francisco from 2004-2011, Newsom’s bold policies on a number of issues led to almost immediate national attention. He held an unabashedly progressive stance on same-sex marriage and proposed a controversial solution to SF’s growing homelessness problem. Some saw his audacity as an asset, while critics labeled him the “philosopher king” as more outlandish ideas, such as massive power turbines under the bay, circled down the drain.

Phil Ginsburg, who worked for Mayor Newsom until 2010 (including as his Chief of Staff), witnessed Newsom’s leadership first-hand. “The Mayor was innovative, fast-moving, curious and excited by policy and bold ideas,” Ginsburg said. “[He] was at times challenged by focusing on too many ideas and policies at once.”

Newsom’s leadership has left a lasting legacy on San Francisco’s political climate and offers hints of his path for the future of California.

Newsom was born in San Francisco and grew up in a family with various connections to California politics: his father was a state appeals court judge for years. After graduating from Redwood High School in Marin, Newsom attended Santa Clara University on a partial baseball scholarship. He received his degree in political science.

After graduation, Newsom and childhood friend Gordon Getty opened PlumpJack Wines, a wine store on Fillmore Street, that eventually expanded to include restaurants, wineries, and luxury resorts. Newsom’s strong business background characterized him as a moderate politician, especially considering San Francisco’s progressive playing field.

Newsom’s moderate image faded almost immediately, however, when he turned City Hall into a wedding chapel only one month after his inauguration.

On February 12, 2004, lesbian activists Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon became the first couple in the country to obtain a same-sex marriage license. Their marriage was the first of 4,000 weddigs of same sex couples that took place over the next 29 days.

At the time, gay marriage was illegal in California. Newsom’s act of civil disobedience was widely criticized among conservatives and progressives alike. Because his policy rallied many conservative activists and voters, members of his own party blamed Newsom for the success of Prop 8, a 2008 ballot proposition that banned same-sex marriage. Even Senator Dianne Feinstein, who has been one of Newsom’s staunchest supporters throughout his political career, publicly blamed him in part for Democrat John Kerry’s loss in the 2004 presidential election, claiming that backlash against Newsom’s actions had heightened enthusiasm and voter turnout among the Republican base.

Kate Kendell, the executive director of the National Center for Lesbian Rights during Newsom’s mayoralty, asked the mayor to wait before issuing the marriage license in February 2004. But once he went ahead, she fully supported his decision to challenge state law. “My initial hesitation was borne out of fear of backlash,” Kendell said, “But history proves he was right.”

Over the course of the year, each of the 4,000 same-sex marriage licenses issued was revoked. Nonetheless, many credit Newsom with bringing the issue to the national stage. While his decision was controversial at the time, it set a legal challenge in motion that eventually led to the 2015 Supreme Court ruling that legalized gay marriage in all 50 states.

“It was one of the highlights of my career to work so closely with Mayor Newsom and his team to realize his bold vision of issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples,” Kendell said. “I knew we were making history, but even I did not appreciate what an impact his move would have on the national fight to win the freedom to marry.”

While initially contentious, Newsom’s policies around gay marriage are widely commended by progressive activists today. However, many of his other policies remain clouded in controversy.

Homelessness was on the rise in the early 2000s, and had become a pressing topic in San Francisco. In 2004, Newsom instituted his “Care Not Cash” policy, an initiative that would provide homeless people with housing instead of welfare checks. At first glance, Care Not Cash was successful. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, homelessness dropped 28 percent in only two years.

Newsom’s idea was that the focus on housing would stop recipients from spending money on alcohol and drugs. But without welfare checks, thousands of formerly homeless people were left without enough money for food and clothing. Many had to resort to panhandling just to meet their basic necessities.

Again, homelessness is high on Newsom’s agenda. In his first week as governor Newsom proposed a budget that included hundreds of millions of dollars to address the statewide housing crisis. During his campaign, Newsom suggested a program modeled off of Navigation Centers — temporary shelters in San Francisco that connect people to healthcare, income, and other public services — that were designed by former Mayor Ed Lee. By providing the homeless with services other than housing, this system could help address the faults in Care Not Cash. However, Newsom still cites Care Not Cash as proof of past success in housing policy, despite heavy criticism from activists.

Another key talking point during Newsom’s campaign was his accomplishments surrounding healthcare. In 2007, Newsom introduced “Healthy San Francisco,” the first city-wide universal-access healthcare program in the U.S.. The program provided each participant access to preventative primary care, mental health services, and a variety of other essential health services.

Over a decade later, Healthy SF continues to provide healthcare to the people of San Francisco. By 2012, around 80 percent of San Francisco’s uninsured adults had joined the program. According to the San Francisco Public Press, access to preemptive care has led to a decline in emergency visits at San Francisco General Hospital.

During his campaign, Newsom promised to extend his Healthy San Francisco initiative into statewide universal healthcare. His goal was to create a government funded, single-payer program — a system that would double the existing healthcare budget and require federal approval.

While his goals are certainly audacious, Newsom has already hinted at plans to follow through on his promises, including hiring cabinet members with experience in healthcare policy. Newsom chose Ann O’Leary as his chief-of-staff and Ana Matosantos as his cabinet secretary, who each have years of experience in the Clinton administration and under Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, respectively. Shortly after his inauguration, Newsom announced a sweeping expansion of Medi-Cal that would cover undocumented immigrants and increase subsidies for middle-class families.

Additionally, Newsom dedicated almost $2 billion of his 2019-2020 budget to early childhood care. His proposals included funding for full-time preschools in low-income areas and childcare facilities on California State University campuses, and extended paid maternity leave from six weeks to six months.

Newsom’s overarching message is a “California for All.” Despite his previously polarizing decisions, occasional jabs across the aisle, and increasingly progressive perspective, Newsom has outlined unity as the foundation of his new administration.

“We will not be divided,” Newsom said during his inaugural address. “We will strive for solidarity, and face our most threatening problems — together.”

Erica Terry Derryck, who worked in the District Attorney’s Office under Newsom, expressed confidence that Newsom has the ability to create change. “Gavin Newsom coupled innovative policy approaches with an ability to navigate the intricacies of San Francisco’s often rough and tumble political landscape,” Derryck said.

When asked, Kendell confirmed her unwavering support for Newsom. “I think he will be a Governor who doesn’t let conventional views drive his decisions,” she said. “He will take risks and be bold to advance issues of justice and equity. He will be a fantastic leader for California and the nation.”