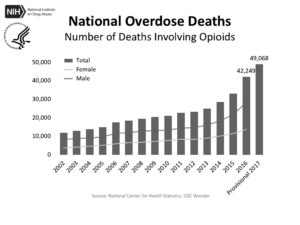

Drug overdoses, including easily obtained prescription opioids, are the leading cause of death among Americans under the age of 50, as reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The National Institute of Drug Abuse determined that out of the 72,000 Americans that died from overdoses in 2017, 49,000 were caused by opioids. Dr. Jonathan Terdiman, the father of Mira Terdiman ‘20 and Joya Terdiman ‘22 a Gastroenterologist at the University of California, San Francisco, describes the opioid epidemic as “a perfect storm of some good intent, some evil-doing, and the addictive behavior of Americans.”

graph courtesy of National Institute of Health

President Trump has declared the opioid crisis a “national public health emergency,” an example of the widespread concern that has provoked change regarding policy, conversations within the medical community, and approaches to pain treatment.

A major, yet often overlooked, factor in what unfortunately determines the reaction and relief to a drug epidemic is race. According to the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, white people make up 80 percent of the opioid overdoses, black people make up 10 percent and Hispanics 8 percent.

According Helena Hansen and Julie Netherland’s article “Is the Prescription Opioid Epidemic a White Problem?” in the American Journal of Public Health, this disproportionality was caused “opioid regulation and marketing, which gave US White patients the ‘“privelage’” of unparalleled access to prescription opioids.” The racial bias and segregation that exist within politics and media have resulted in more policy change and an overarching belief for widespread opiate addiction therapy.

Knight Knight, an Associate Professor of Anthropology, History and Social Medicine at UCSF, adds that this sympathy was not expressed “[for] other communities who have been really impacted by drug epidemics in the past such as the crack-cocaine epidemic in the African American community.” America’s response to the crack-cocaine epidemic of the 1980’s and 90’s consisted of punitive police tactics and harsh prison sentences unlike the shift toward drug treatment and prevention that results from the current crisis.

Opioids are strong, addictive painkillers. Dr. Adrian G. Bartoli, a pain management doctor for Sutter Health in San Francisco, used the example of a pinprick to explain how opioids eliminate pain. If one were to prick their finger with a pin, neurons would be transmitted from the finger to the brain, and this signal would be interpreted as “pain.” The human body naturally alleviates pain by releasing endorphins that bind to pain receptors, causing the neuron signals to slow down. Opioids mimic these endorphins, resulting in a dramatic suppression of pain, and a feeling of pleasure or a “high.” Doctors often prescribe opioids, such as Vicodin, Percocet and Oxycontin, for both acute and chronic pain. Sudden injury or surgery can cause acute pain, ongoing conditions like arthritis cause cronic pain. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention revealed that out of the 33,091 opioid overdose deaths in 2015, 15,281 died from prescription opioids. Prescribing excess amounts of opioids causes dependancy and addiction in many patients. According to the U.S. National Library of Medicine for the National Institute of Health (NIH), between 21 to 29 percent of patients who are prescribed opioids misuse them.

Many who are misusing the painkillers are no longer patients, but people who just to sastisfy their addiction. There have been several cases of patients selling their opioids, opioids being stolen, or overlapping prescriptions from multiple doctors to get more than they need. The high price of prescription opioids opens the door to heroin use for opioid addicts, an illegal opioid that has the same effect on the brain. Kapp Singer, a Lick alumnus who worked in a needle exchange in San Francisco, which many heroin addicts use for safe injection, stated that “A lot of the work that I was doing was directly because of the collateral damage from overprescription. A lot of the people that ended up addicted to heroin started through pain pills.” In fact, a study conducted by the National Institute on Drug Abuse demonstrated that 80 percent of heroin addicts had 4first misused prescription opioids, revealing prescription opioids to be a “gateway drug.”

Over the past 40 years, the approaches to treating pain have changed drastically. Bartoli notes that in the 70’s and early 80’s chronic and acute pain were usually treated with a combination of acupuncture and other tratments from Eastern medicine, chiropractic treatment, and psychotherapy.

In the 90’s there was a surge of the prescription of opioid medications, causing the use of these other regimens to decline. Purdue Pharma and their release of a new prescription painkiller, Oxycontin, incited this increase in 1995. Purdue Pharma’s marketing advertised the risk of addiction for Oxycontin as less than one percent. The drug was actually highly addictive, a fact Purdue Pharma knew from the beginning.

In 2007, the company pleaded guilty to “misbranding” Oxycontin. According to the NIH, the misleading message resulted in Purdue’s profits ballooning from $48 million in 1996 to $1.1 billion in 2000, and caused widespread misuse and addiction in America. Dr. Terdiman notes that during the 90’s, patients felt doctors did not adequately treat pain. “Some of this [feeling] secretly was being funded and promoted by the companies that make the opioids, but it was all filtered through graduate medical education… you needed to be more aggressive about using opioids to make sure that your patient wasn’t having pain.”

The rise in addiction and overdose as a result of this epidemic has sparked a debate on prescription amounts within the medical field. Bartoli notices that a group of physicians still passionately believes that opioids should not be harshly regulated, and a group who simply believes that prescribing “a modest amount of opioids in a cautious fashion” can be just as effective. Dr. Lawrence Yee, a colon and rectal surgeon at California Pacific Medical Center, describes this epidemic as a “wake up call” for many doctors — many have drastically changed their prescribing habits.

Yee now prescribes a third of the tablets what he would have given a patient twenty years ago after the same procedure. Furthermore, Terdiman admits that he was “a lot more liberal with opioid prescriptions 10-15 years ago,” and that his prescription habits have evolved in response to this epidemic. “I avoid opioid prescriptions in most circumstances.”

Not only are opioid prescription amounts decreasing, but doctors have begun to favor alternative drugs and pain suppression methods over the narcotics. Terdiman made it clear that he considers all non-opioid alternatives before prescribing opioids to a patient. These methods include reverting to nonsteroidal drugs, mindfulness, meditation, acupuncture, and spinal cord stimulation. Terdiman notes that the wariness and suspicion expressed by doctors are often “not good for doctor/patient relationships,” because patients may feel as though their doctor doesn’t trust them with the opioids. In certain cases, patients feel like their doctors are “being over-cautious” and “neglecting to treat pain” by favoring previous non-opioid methods.

But technological advances within the past decade have resulted in alternatives for pain management that may appeal to more patients in the future, such as the use of virtual reality. Bartoli describes virtual reality (VR) as one of the “brightest prospects” for pain treatment.

Karuna, a company that uses immersive virtual reality, claims that VR can help calm the nervous system, increase the range of motion and serve as a distraction to patients’ pain and physical limitations. Terdiman says that “Americans expect medicine to take care of everything for them.” Therefore, VR allows patients to self-advocate in their personal treatment, as they are not relying on a pill for pain relief.

Medical professionals have also adapted to prevent a common method of obtaining opioids: having multiple doctors who, unaware of the overlap, prescribe the same drug to a patient. Cures 2.0, a prescription drug monitoring database, allows doctors to record their prescriptions and see what drugs they administered to their patients to avoid excess prescriptions. Dr. Peter Callander, an orthopedic surgeon at Sutter Health in San Francisco, says, “If I have a patient that asks for medication, I may get alerted and say, ‘you know what, this patient also got some from another doctor.’” This allows doctors to be confident that they “are all on the same page.” Callander thinks that this system, which was mandatory among statewide opioid prescribing health practitioners by the California Department of Justice on October 2, 2018, is “a good tool to help protect not only the patients but the prescribers” and that it will “put a dent in this epidemic.”

Encouraged by the scale and publicity of this epidemic, these conversations are still evolving. Terdiman believes the next step in addressing this epidemic includes “educating doctors about all the tools available to treat pain,” as most of his colleagues “are completely unaware of all the things that they could martial to help with the pain.” The treatment is just beginning.