To read or not to read? Within the past few years, high school English teachers across the country have asked this question amidst debate over whether traditional literary classics are still relevant in today’s English curriculum.

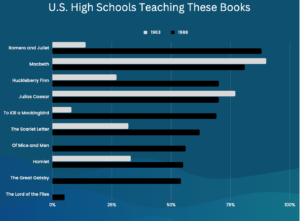

Since the mid-late 20th century, the books included in the U.S. high school English curriculum have remained fairly constant. According to a 1989 study by English professor Arthur N. Applebee at the University of Albany, the most common high school reading texts were Romeo and Juliet, To Kill a Mockingbird, Of Mice and Men, The Great Gatsby and The Lord of the Flies. These texts are often referred to as the literary canon, or a body of texts that have been consistently taught across the U.S. for decades as staples of the typical high school English curriculum. However, in recent years, teachers and students across the nation have debated whether our literary canon is truly inclusive and representative.

“Generally, classics means a shorthand for books that educated people are supposed to have read, and in this culture, those are usually [written] by white men,” Lick-Wilmerding High School English teacher Jennifer Selvin said.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the literary canon underwent significant change when many of the books included were first published. According to a 1963 study by Scarvia Anderson and a 1989 study by Applebee, the 1960 novel To Kill a Mockingbird was taught by 8% of high schools in 1963. By 1988, that number increased to 69%. Similarly, William Golding’s 1954 classic The Lord of the Flies was taught by 0% of high schools in 1963. By 1988 it had risen to 54%.

60 years later, the literary canon is once again evolving. Movements to diversify high school English curricula have emerged in the past few years such as #DisruptTexts, which is a teacher-led “grass roots effort to challenge the traditional canon in order to create a more inclusive, representative, and equitable language arts curriculum,” according to the #DisruptTexts website. This organization was founded by four teachers of color and provides guides for educators on how to read books within the traditional literary canon with a critical eye. Additionally, #DisruptTexts provides teaching and learning guides, as well as recommendations, for contemporary novels that center BIPOC voices.

Many students, especially those who identify as minorities, may feel a disconnect from western literary classics that only represent a small portion of the student population. “[Diversifying the English curriculum] is definitely a step in the right direction, especially if these stories are not relevant to all the communities that schools across the country are supposed to be serving,” Co-Student Inclusion Chair Nathan Rivera ’24 said. “Students should be able to see themselves reflected in the curriculum. Even in some small way, like resonating with how the character talks or lives day to day.”

In the past few decades, the literary canon classics have been considered to be integral to a high schooler’s education. One’s exposure to classical literature has often been treated as a measure of literary knowledge and college readiness, a practice that dates back to the beginning of the 20th century. According to Charles van Cleve’s 1938 journal article, The Teaching of Shakespeare in Schools, the inclusion of Shakespeare in the high school curriculum was determined by college entrance requirements at the time.

But in recent years, many teachers and literary scholars have begun to reconsider this mindset. “The biggest thing is gatekeeping. This idea that an educated person has to read [classics], or that people will be behind if they haven’t read [certain texts] before they go to college,” Selvin said. “It’s a way of keeping the class structure the way that it is and extracting value from something that doesn’t have to be commodified. I don’t want to have a world where knowing those things is a mark of intelligence.”

The current LWHS English curriculum is extremely diverse, with a selection of texts that center many different races, ethnicities, backgrounds, sexual orientations and other identifiers. While classical literature is not entirely bereft from the curriculum, several books have been phased out over the years as English teachers have continued to develop the reading list. This includes The Catcher in the Rye, The Scarlet Letter and The Great Gatsby.

LWHS and other independent schools are unique in the fact that they do not have a required reading list that teachers must follow, unlike many public schools. The LWHS English department is given the freedom to independently choose the curriculum each year.

“We think about representation [when creating the curriculum]. We want our students to understand that writers are different races, different ethnicities, different genders…just to represent the full spectrum of who’s writing. It’s this idea of windows and mirrors. We want students to both look at a text and see the way it mirrors their own experience and the way it’s a window into somebody else’s experience,” Selvin said.

Leader of the LWHS Banned Books Club Henrietta Benziger ’24 does not feel as if the English curriculum’s lack of books from the literary canon has lessened her learning experience. “When you look at those books, they don’t represent the demographic of who we are as Americans. Our English classes [at LWHS] are centered around understanding the American experience, and if the diverse American experience is not represented in the books we’re reading, then we can’t truly call our class an exploration of American identity,” she said.

However, the case can also be made for continuing to read traditional literary classics in an educational setting. LWHS English teacher Judy Butterfield believes that classical literature that has traditionally been taught in high schools for the past several decades can offer a window into a previous time period. “I don’t think that it’s useful to say that people shouldn’t read [certain texts], because it is important to be able to interact with and think critically about people and times and places that are problematic. That is part of our history,” she said.

LWHS English teacher Rex Shannon teaches the senior English seminar Existential Shakespeare: That is the Question, which analyzes Shakespeare’s plays and discusses contemporary issues of race and inequality through an existential lens. Shannon believes that many of the texts analyzed in the class have remained timeless and relevant for students today.

“Romeo and Juliet is a romance from the 1500s, and yet, I felt like the students identified with that sort of love between Romeo and Juliet,” Shannon said. “Shakespeare also gives you insight into a time and a place, which is really exciting. It teaches you a moment in time, but you also get the relevance to today.”

For many students, the issue with the literary canon is that the texts are required for high schoolers to read, and many students may not resonate with or feel represented by the reading list. “If you want to look at the historical aspect of what language people used and what ideas they had about the world, then I would say go for it. It’s about [the literary canon] being required in the curriculum that is the issue,” Rivera said.

However, if modern-day education phases out all classical texts, it may result in a blind spot when reading and analyzing contemporary literature. “So many [authors of] English written work have read Shakespeare. If we’re not reading what contemporary authors have read, then we’re missing some stuff,” Butterfield said.

Thoughts surrounding the literary canon and books considered to be classics are constantly changing. PEN America’s Index of School Book Bans recorded 2,532 instances of individual books bannings from June 2021 to June 2022. This uptick closely parallels the widespread banning of books in the 20th century that are now considered to be literary classics, such as Catcher in the Rye, The Grapes of Wrath and To Kill a Mockingbird.

In the midst of these nationwide debates over school reading lists, Benziger believes it is important to note that the definition of an American classic is continuously evolving. “We’re advancing the definition of a classic into something that continues discussions, but also represents more people in the voices and experiences that are written about. I think that’s why you see a lot of previously banned or challenged books now starting to be considered classics,” she said. “Toni Morrison, especially, is one that comes to mind. [Her writing] pushed people to think. Books that affect society are the ones that become classics.”

Benziger believes that the value in reading classics lies within their historical viewpoints. “We are able to educate ourselves through literary knowledge about past experiences and issues to understand what the climate was like then, versus what the climate is like now,” she said. “It’s reassuring to see your progress, and then remind yourself that there is more to do.”