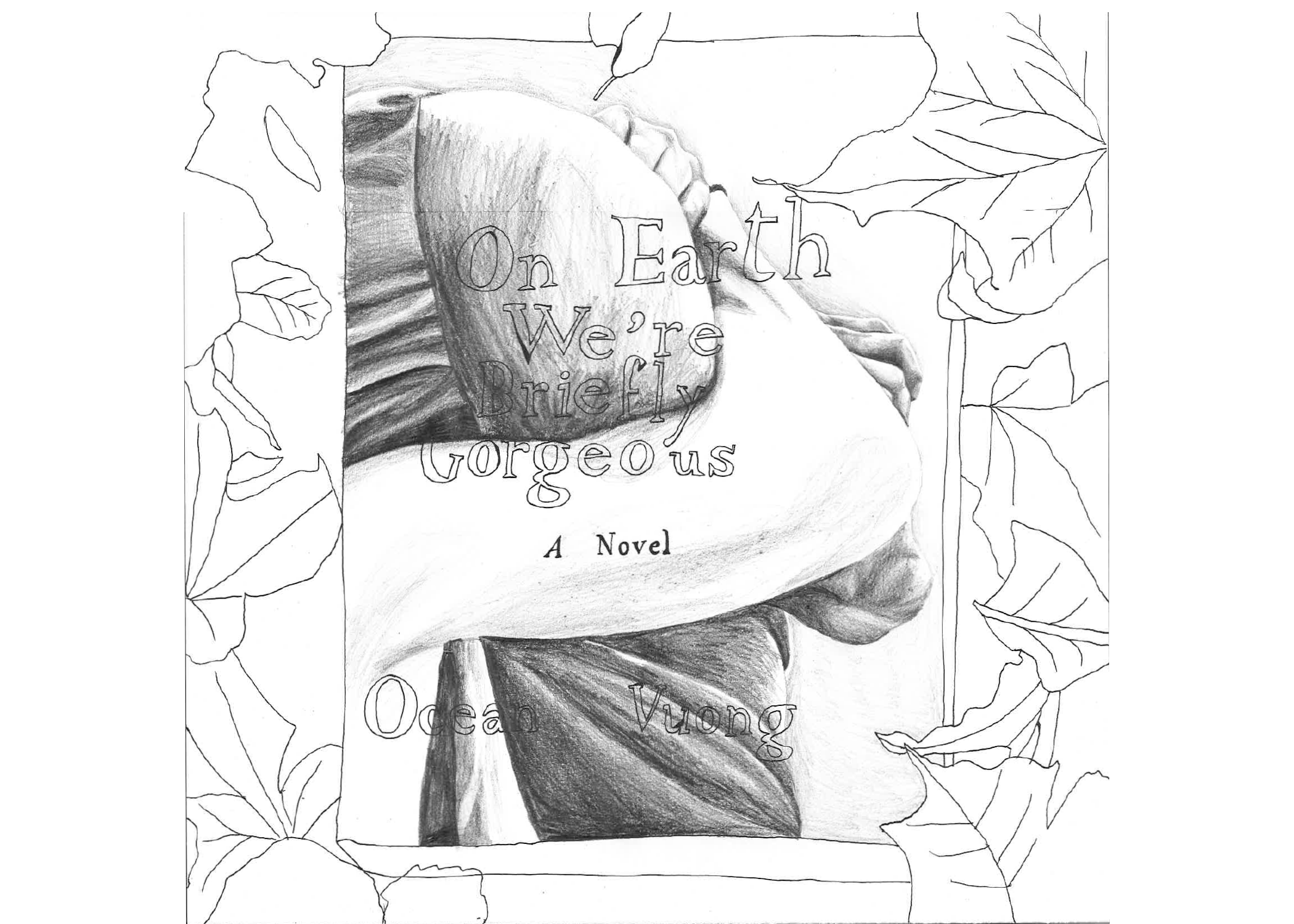

Ocean Vuong’s first novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, is written as a letter from Vietnamese-American boy to his mother, Rose. Vuong was born outside of Ho Chi Minh City on a rice farm in 1988, and emigrated to the US in 1990. This novel is an exploration of the power of language, both to bring people together and to separate people. By writing a letter to a mother who doesn’t have the language skills to read it, the narrator reveals how language barriers define his relationship with his mom—how language has always been a prison for her, and how Vuong has transformed language into his attempt to find freedom for himself.

I read this novel as a love letter, but a love that is tainted by trauma and violence. Narrator and protagonist Little Dog starts his letter by looking back on his relationship with his mother and many of his memories do seem nostalgic. Interspersed between these memories are other, darker memories: “The first time you hit me… the time you threw the box of Legos at my head… The time, at thirteen, when I finally said stop.”

Instead of excusing his mother’s violence with the loving things that she did for him, Little Dog holds all different parts of his relationship with her into his definition of love, including the painful ones.

He also includes intergenerational trauma in love. One day, when Little Dog and his mother are gardening together, she randomly blurts out that she is not a monster. Little Dog wants to tell her that she is a monster, but that “a monster is not such a terrible thing to be. From the Latin root monstrum, a divine messenger of catastrophe, then adapted by the Old French to mean an animal of myriad origins: centaur, griffin, satyr. To be a monster is to be a hybrid signal, a lighthouse: both a shelter and warning at once… Perhaps to lay hands on your child is to prepare him for war… I don’t know.”

Little Dog first encounters storytelling when he listens to the stories of his grandmother, Lan, who helped his mother raise him. Lan tells him stories of her traumatic past through the lense of her PTSD and schizophrenia. As she tells stories, he uses tweezers to take her white hair—her age, her past, her trauma, her “snow”—out of her life. This storytelling is a way for Little Dog to connect to his grandmother. Lan’s obsessive storytelling of her traumatic past and her need to get that past out of her is also an expression of her madness, but, as the Little Dog says, “madness can sometimes lead to discovery, that the mind, fractured and short-wired, is not entirely wrong.”

Lan calls her grandson Little Dog because of the tradition in their village to name the weakest person in a group after an undesirable creature. Evil spirits would only try to attack beautiful and healthy children, and would spare those with names like Little Dog. For Lan, “A name, thin as air, can also be a shield.” Lan and Rose are powerless in many ways—they can speak very little English, they have lived through abuse and war, they have to single handedly raise a child in a sexist, racist country. But the name Little Dog is a way for them to have power, to protect and fight for their child.

In his teens, Little Dog meets a boy named Trevor when working at a tobacco farm, and they begin to fall in love. “He loves me, he loves me not, we are taught to say, as we tear the flowers away from its flowerness,” the author writes. “To arrive at love, then, is to arrive through obliteration.” It is a beautiful and heartbreaking relationship that contains internalized homophobia and hurt, but, according to Little Dog, “by then, violence was already mundane to me, was what I knew, ultimately, of love.”

Maybe for Little Dog, love is “a deep purple feeling, not good, not bad, but remarkable simply because you didn’t have to live on one side or the other.”

This book was hard to get into at first, because the language almost felt too beautiful and poetic for me to become attached to the story or the ideas. But as I read a little bit further, I started to feel personally connected to the book. Because it was a letter, I felt like Little Dog, and, in a way, Vuong himself, was writing to me. There was a sense of urgency I felt as I read it, because I needed to read about people I felt like I knew.

This book is one of the most painful and deeply sad books I have read. His language felt like it physically stabbed me and ripped me open. He talked about the way that even writing itself is described violently: “You’re making a killing with poetry. You’re knockin’ ’em dead.” Although his language hurt me, it eventually healed me.