Large scale paintings, story quilts, stuffed soft sculptures and more from fifty years of Faith Ringgold’s comprehensive career decorate the halls of the de Young Museum. The exhibit is titled “Faith Ringgold: American People” and is on display from July 16 to November 27. “American People” features work from Ringgold’s “Black Light” series, the “French Collection” and the exhibit’s titular “American People” collection, among other pieces from across her career.

Born and raised in Harlem, New York in 1930, Ringgold grew up entrenched in the Black creative scene of her neighborhood’s Harlem Renaissance. With notable figures such as Langston Hughes and Duke Ellington living only blocks away, she became aware of the power and expansiveness of art from a young age and continued to learn more in her adolescence. Ringgold went on to enroll in the City College of New York in 1948 to earn her degree in fine art, but was quickly turned away from the program because of her gender. By becoming a teacher, Ringgold was able to study art anyways and majored in art education instead; she graduated with her bachelor’s degree in 1955.

While the Civil Rights and Black power movements raged across the country in the 1960s, Ringgold’s art underwent a transformation marked by her “Early Works,” “American People” and “Black Light” series. Rejecting the ideas she had learned during her education that art could only be picturing still lifes or landscapes, she embraced a new technique she called “super realism” to communicate the hostility and tension of the decade.

Ringgold incorporates a wide variety of processes throughout her art, consistently using bold colors and manipulating scale and perspective within her paintings to draw the viewer’s attention.

Frances Homan Jue, the writer and producer of American People’s audio tour, discussed what separates Ringgold’s craft from other artists of her time. “She’s just able to go from huge, broad scale and boldly experimenting with stitching and painting fabric to very delicate watercolors and paintings on a small scale as well,” she said.

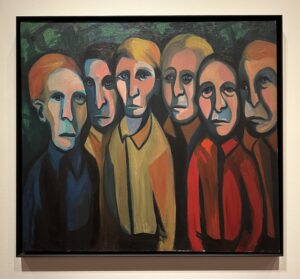

Pieces like “Early Works #15: They Speak No Evil” (1962) and “American People Series #2: For Members Only” (1963) that are featured in the exhibit recreate frequent interactions Ringgold experienced with white people which left her feeling like an outsider. Both oil canvases portray white ghoulish faces, utilizing dark shading and penetrating stares to place the viewer in the ostracization Black people experienced in believed white spaces during the time period.

photo by Senai Wilks

Ringgold continued to build on the idea of mid-sixties race relations with one of her most recognizable works from the American People collection, “The Flag is Bleeding” (1967).

photo by Senai Wilks

Hung on the de Young’s walls, “The Flag is Bleeding” displays a Black man, white woman and white man linking arms in the backdrop of the American flag. With a knife in hand, the Black man holds his hand to his heart, both in a show of patriotism and as a way to staunch the blood spewing from his wound that also leaks from the flag’s stripes. The painting offers the viewer no explanation for the man’s gash, simply placing him next to the white woman who connects him to the other man whose hands cling to his gun holsters.

Ringgold explains in the audio tour of American People from MOMA archival recordings that she strived to be able to reflect the turbulent civil unrest of the sixties through her art, especially in pieces like “The Flag is Bleeding.” She describes how, during this period, all everybody she knew could talk about were the spontaneous rioting and violence against Black bodies happening in the streets; however, the truth failed to broadcast on public television and in the homes of those who ignored the issue at hand.

As a result, Ringgold found herself asking how she, as a Black female artist, could document what she was seeing happen to her community across the country. Her internal questioning pushed her artistry forward as she answered this question throughout her later pieces. Instead of allowing the violence against her community to force her into silence, Ringgold fought back and used her art to challenge the brutalities that plagued the decade.

From this point forward, political and cultural themes became integral to Ringgold’s paintings and activism a key part of her career, clearly displayed in her work from the following years.

Surrounded by other works such as “America Free Angela” (1971), protesting Angela Davis’s 1970 arrest and “All Power to the People” (1970), in support of the Black Panther Party, “United States of Attica” (1971-72) hangs on the de Young’s walls as part of the Art of the People section.

In response to the National Guard and New York police’s killing of 42 inmates from Attica Correctional Facility following a peaceful protest four days prior in 1971, Ringgold created the lithograph map entitled “United States of Attica” which charts the history of American violence. Painted with the Black liberation movement’s red and green, the poster features the first forty eight states with scrawls detailing specific acts of inhumanity committed within each state starting from the Colonial Era until 1972. The poster forces viewers to confront the truth behind United States history through the bottom inscription which empowers them to write in other brutal events as they see fit, participating in Ringgold’s belief in community activism.

In the audio tour, poet and Black Panther Party education director, Ericka Huggins, described how the Panthers “were changing the way of being in the United States, by showing up.” Similarly, Ringgold altered the way people viewed America and interacted with their identities through her art that challenged racism, police injustice and misogyny, forcing her audience to critically evaluate their country.

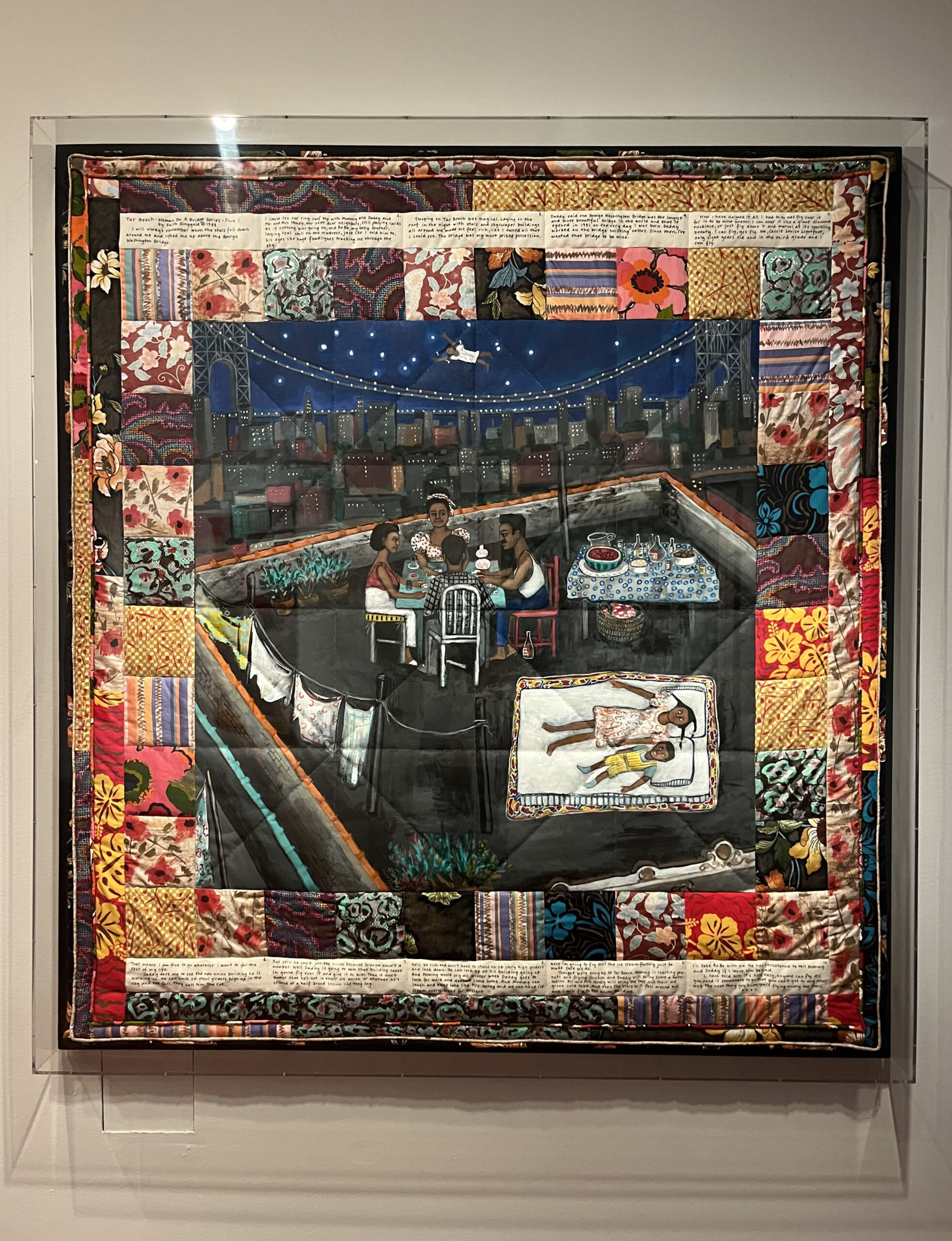

In addition to creating powerful political art, Ringgold is arguably best known for her dynamic storytelling through her innovative story quilts that decorate the last three rooms of American People. Her quilts consist of wide cloth backgrounds which feature Ringgold’s paintings and are inlaid by fabric borders that write out the story depicted in the center of the quilt.

Ringgold’s unique quilted paintings came as a result of her difficult journey to be seen as a serious artist. For years, she struggled to book any shows and once she did, she had trouble paying the expensive shipping fees of her painted canvases. Emily Miller, art teacher for both upper and middle school students at Head-Royce School, applauded Ringgold for her tenacity in the face of constant rejection. Miller commended how Ringgold “in turn, look[ed] back at her own life and [thought], ‘Where can I find the solution in my own people?’” she said.

One of her most famous story quilts, Woman on a Bridge #1 of 5: Tar Beach (1988), lines the walls of the de Young, both in its original form and framed drawings of its eventual 1991 children’s book adaptation

The quilt depicts a 1930s Harlem rooftop at nighttime as the series’ protagonist Cassie Lightfoot and her brother gaze up at the night sky from a mattress and cool off from the summer heat. Amidst the city lights and snapshot of the George Washington Bridge, the viewer can also see the figure of another girl flying above the city in only her nightgown and braids, an image which appears in much of Ringgold’s work.

Laurel Nathanson, Lick-Wilmerding High School Jewelry and Textiles teacher, spoke about the craft behind Ringgold’s iconic narrative quilts. “She’s combining this looser quality, but she’s also playing with traditional components of fine art,” she said. “There’s sort of this rigid way of quilting that people really gravitate towards and appreciate because it’s very technical, but that’s just one aesthetic.”

Homan Jue acknowledged the immense legacy and importance of Ringgold’s quilts, “Faith Ringgold takes her quilts which, on the one hand, are very simple things that keep people warm, but her quilts have such incredibly complex meaning to them with many layers.”

More than thirty years since its original release, Tar Beach remains a beloved piece for many and encapsulates the freedom at the heart of each of Ringgold’s pieces portrayed through the flying girls.

The figure overhead takes on the city to find a place for herself among the stars, similar to how Ringgold formed her own place in an art community which struggled to allow a Black female artist to receive the acclaim she deserved and has rightfully found today.