Consent education and rape culture at Lick-Wilmerding High School have long been undergoing a reckoning.

This will be the fourth year that LWHS has taught the Soph Health: Human Sexuality class. The class took ten years to get approval and was finally implemented in 2017, due to overwhelming pressures from parents and students.

Currently, ninth graders only learn about consent in Biology through a unit on human reproduction. After learning about physical anatomy and STDs, students play a game in which they “share fluids” and practice consent by asking before they “share.” The teacher may then teach some basics of consent

However, consent is by no means the core content and “how much each teacher dives into the topic of consent is variable,” said ninth grade biology teacher Gillian Ashenfelter. The biology teachers are tasked to teach the fundamentals of consent without any formal training. As a result, teachers have varying levels of comfort and skills to teach such an important concept.

Erin Merk, Body-Mind Education (BME) Department Chair and Program Faculty, said that her department had previously believed that the counseling department had taken on the consent education for the ninth grade in the form of assemblies.

However, in 2020, when LWHS began distance learning, the counseling department dropped consent education for ninth graders and decided to use their limited assembly time to present on issues that they believed were of a higher priority. These issues were eating disorders and navigating pandemic isolation.

Previously, the BME faculty believed sexuality education for ninth graders, along with counseling assemblies and biology classes in the spring, would be too repetitive. “But now we think, maybe not. We’re realizing maybe now we need to be in charge of that, since there doesn’t seem to be a regular, ongoing presentation,” Merk said.

“As far as I know, there hasn’t been any explicit consent education for the ninth graders,” said Merk. “So this year we expanded our substance education unit, and we’re going to fold (consent education) into that through the lens of party culture.”

Students in their second year at LWHS explore consent and healthy relationships throughout the semester long Soph Health class in the fall or spring. This course is made up of 40 classes, each 70 minutes long.

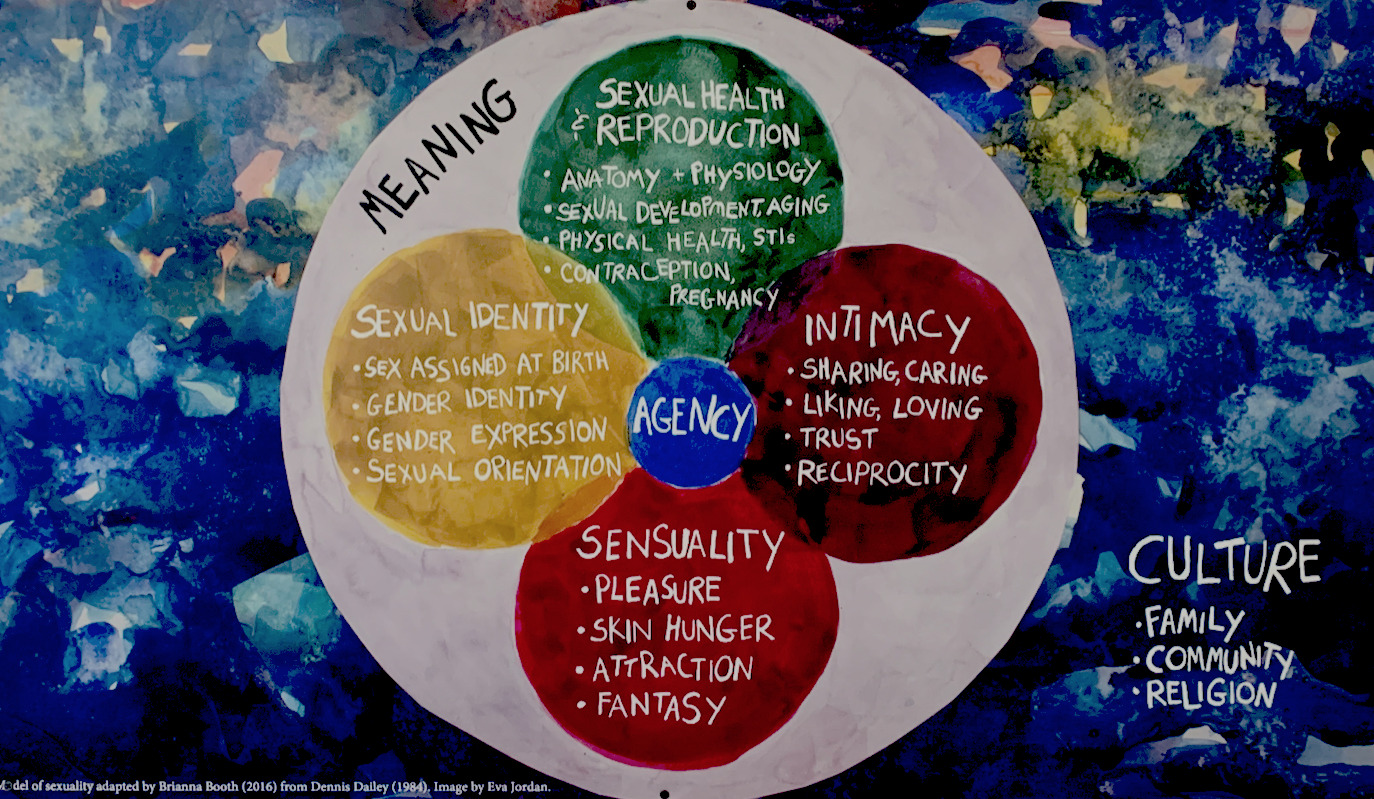

The Soph Health class spends five classes explicitly on a consent unit. Merk expanded, “It’s also really the center of our entire course, because it flows through every other aspect of sexuality. Once the consent unit is officially complete, it doesn’t end, it just kind of gets more robust and complex.”

The BME class begins with the basics and defines what consent is. Then, students begin reading 45 Stories of Sex and Consent on Campus from the New York Times. These stories open up the conversation to more nuanced issues of consent involving stories of people saying yes when they did not want to have sex, stories involving substances and stories of sex that is not positive or pleasureable. Merk said, “Through a whole class discussion, students then try to bring their ideas for what it would actually take to transform the culture into a space where people really truly embodied consent on all levels.”

Conversations about specific dynamics at LWHS are not avoided, however, whether or not they are broached typically will depend on students’ comfort levels. “I always want to leave it to them to bring up what they feel comfortable bringing up,” said Merk.

Maddie Garfinkel ’24 believes that the education they have received from LWHS has been nowhere near enough. “I think they should really emphasize consent on the first day of ninth grade. It should be the focus of showing up to a new community, especially given that rape culture and assault are so prevalent at Lick, just from people I’ve talked to.” they said.

Garfinkel also believes that the content of the curriculum could be better revised to meet the needs of the community by speaking directly to the students. They said, “At the very least, they need to get some serious student input. People have been talking about this curriculum not being at the level that it needs to be for a while. I love the health teachers, but there needs to be a serious change in the ways that we talk about consent.”

The current semester class system also leaves many without any consent education until the end of their sophomore year. “I think sophomore year is way too late to be having these conversations,” said Eliana Goldfarb ’22.

The consent curriculum for upperclassmen is condensed into an hour long assembly. This year’s assembly was led by Huckleberry Youth Health Center.

Some students expressed frustration following the assembly due to its oversimplification and detachment from the real issues that students are facing. Goldfarb said, “Obviously, consent and boundaries are important to review. But that’s what we learned in sophomore health. And the issue is a lot more complicated than that.”

Simply reinforcing the same concepts over and over for many sessions — whether it be in ninth-grade Biology, Soph Health or assemblies — is not the same as a more dynamic complex kind of education that speaks to the needs of the students.

The assembly format was a challenge for some students; students were not required to engage or think actively. Because the assembly consisted of simply defining consent and playing games like charades, it was easy for students to joke around and not reflect seriously on the messages presented. A required assembly of this nature possibly could be triggering for some survivors.

The LWHS’ counseling department received feedback via survey that the assembly fell short of some student’s expectations because the information had already been covered in their ninth and tenth grade classes. Counselor Erika Solís said, “I think that (the eleventh and twelfth grade curriculum) is an area for growth, so upperclassmen can have opportunities to further learn and discuss.”

Although sexual assault can happen at any age, as students get older, sex and partying become more common. During this time when students are more directly faced with these situations, they lack a space for support and open mature conversation.

Goldfarb believes that workshops for upperclassmen — similar to the format of the workshops on Sam Mihara Days of Justice — would be much more effective at opening up a space for discussion about assault specific to their experiences.

Merk and BME Faculty member Diana Suárez-Vargas are also in favor of creating an extension of the curriculum for older students. Suárez-Vargas said, “The sophomore class for me is a foundation. We definitely need more robust education for older students.”

Merk and Suárez-Vargas believe in a similar workshop extension of BME. Merk said, “I think it would have to be a multi-session set of workshops with different themes that people feel resonant with. They could choose so that it’s not like, ‘Ah, I’m being forced to go to this dumb workshop,’ but actually like, ‘oh, I think this is something I’m interested in as a male identified person, or here’s something I’m interested in as a queer person, or here’s something I’m interested in as a queer person of color.’ You could actually have some affinity space.”

Students have been rallying recently to make changes in the way that the school teaches consent. On January 24, Fostering Activists in the Next Generation (FANG) Club hosted a meeting inviting students to discuss changes they would like to see to the Soph Health class, attracting over 20 passionate students. They plan to take the ideas generated during their meeting to the BME faculty and administration.

Goldfarb has also been working with Dean of Students Kate Wiley as a part of a working group generated by Dr. Catherine Fung’s ethnic studies class in order to initiate more change as well. One of their main goals is creating workshops instead of assemblies and addressing the sexual assault protocol at LWHS.

Many students have found a strong and clear definition of consent and harassment in the handbook, but feel as if there is a lack of information on what to expect when reporting instances of assault to the school.

The procedure for reported sexual assault between students is: “If a student reports that another LWHS student was involved in the sexual abuse, the School will address the other student’s conduct in accordance with the Policy against Harassment.”

The Policy against harassment states: “A single incident of prohibited harassment could be grounds for dismissal or expulsion, depending upon its severity.”

Survivors often choose to not report any instances of assault for fear of retaliation, shame, feeling as if the assault was not significant enough to report, fear that the justice system would fail, not wanting to get the offender involved with the law or not wanting family or friends to know about the assault. A report also often requires survivors to recount traumatic stories over and over which can be painful. The survivor may want to not think about it any longer and choose to process it alone or with close friends and family.

Reporting also complicates seeking out support for survivors. Once a mandated reporter knows about an assault, the survivor cannot always prevent steps from being taken if the school believes they need to take action to protect the community.

All LWHS faculty are considered mandated reporters, including the counseling department.

An instance of sexual assault involving someone who is a minor at the time of the assault is an instance of child abuse. When this information is disclosed to a mandated reporter, they are mandated to contact Child Protective Services (CPS), administration and the parents of the survivor. Administration would then hire an external investigator. CPS or the police may conduct an investigation as well.

If a student was not a minor when the assault occurred, it is no longer an issue of child abuse but an instance in which a potential crime has been committed. In this instance, the counseling department supports the survivor with a response that involves more nuance regarding what that they would like to do.

According to LWHS counselor Yuka Hachiuma, these steps are done not only to get support for the students involved with the assault, but also to keep the greater community safe.

If a student would like support without the involvement of admin, CPS or parents, they should contact San Francisco Women Against Rape (SFWAR). According to the SFWAR website “SFWAR counselors are NOT mandated reporters. Youth are welcome to utilize SFWAR services for support. SFWAR will NOT contact the police without permission.”

Garfinkel said, “I am excited to see positive change and hopefully trusted adults at this school that students can go to without the fear of being reported. There’s so many people that don’t have adults in their lives they feel comfortable going to. As important as it is that these things get reported, the first step isn’t always to run straight to the authorities.”

Because of the nature of consent education and reporting at LWHS, sexual assult is a part of a student experience that transpires with very little adult awareness.

Assault is often intertwined with partying and substance use. Aahana Mehta-Vasisht ’23 believes this further keeps students from wanting to have conversations about assault because the solution is often seen as abstaining from partying. She said, “It’s a very large ‘push it under the rug and don’t bring it up again’ culture.”

She believes that the conversation should involve more nuance and instead focus on ways to make substance use and parting safer.

Social ostracization — choosing to not be friends with and excluding someone who has been accused of assault — is often the only means of justice when students only have each other. Goldfarb said, “Cancel culture is definitely a problematic thing, but the severity of the issue has gotten to the point where that’s what students have to do to deal with it.”

Goldfarb continued, “Being socially ostracized will not really make anyone learn. Like, they’ll be like, ‘Oh, yeah, I shouldn’t do this because I’ll lose my friends.’ They are not actually learning from their mistakes and then they can go to college and be around people that don’t know all the things that they’ve done.”

Reducing sexual assault to high school drama can make heavy issues palatable for other people to handle. However, when something as personal as assault is reduced to the latest piece of gossip, the individual involved can also feel further stripped of their own agency in situations in which they already might feel powerless.

This all plays into rape culture. Goldfarb said, “The way rape culture works is the smallest things are normalized. And then, once those things are normalized something as drastic as like, an intense sexual assault or rape doesn’t seem like as big of a deal.”

“If someone has been sexually assaulted, it’s about completely feeling powerless and out of control in that situation,” said Hachiuma. The LWHS counselors aim to support survivors by “providing them a sense of agency and control as much as possible in this process of getting support for themselves,” said Hachiuma.

Support can also come from family or friends. If a friend has been sexually assaulted, begin by believing and listening without judgment. Let them know that they are not alone. Offer your time and support. Give them control over the situation by empowering them to understand their options. Offer to support them in whatever their decision is and respect their confidentiality.

Make time to check in and continue to provide support. Healing is in no way linear and can look different for everyone. “Remain available to listen and be aware that this could be something that impacts them in a variety of ways for an extended period of time,” said Solís.

If you or a friend has experienced assault, don’t be afraid to contact counseling@lwhs.org or counselors individual emails: esolis@lwhs.org and yhachiuma@lwhs.org. They are happy to provide the support and resources you need. There is no expiration date on getting help or reporting assault!

These organizations also have resources for counseling:

SFWAR (San Francisco Women Against Rape) – 24/7 Hotline (415-647-7273)

“SFWAR counselors are NOT mandated reporters. Youth are welcome to utilize SFWAR services for support. SFWAR will NOT contact the police without permission.”

“SFWAR counselors hold confidentiality except in instances of suicidal behavior or homicidal plans.”

RAINN (Rape Abuse Incest National Network) – 24/7 Hotline (800-656-4673)+ live chat

La Casas de las Madres