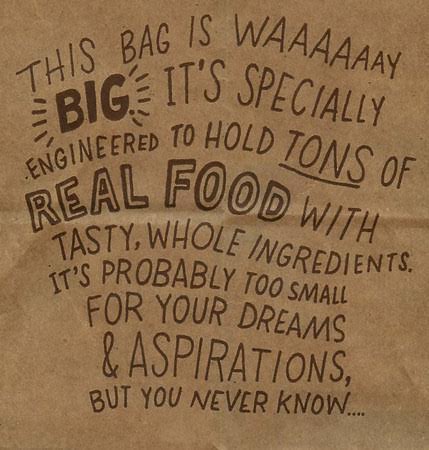

The promise of a good Chipotle burrito is mouth-watering. The message Chipotle’s advertisements send is clear: everyone loves a good Chipotle burrito. The service is fast, the atmosphere casual, the price reasonable and the food both delicious and healthy. The servings are more than generous, heaped with small mountains of cheese, sour cream and rice, wrapped in fluffy flour tortillas, complete with promises of “organic,” “healthy,” “all natural” and “quality” food, written in playful fonts on its packaging. Chipotle’s short, animated films demonize industrial agriculture. Its motto “food with integrity,” promotes its image as the ethically and ecologically responsible place to eat. This image greatly appeals to a younger generation of diners, who believe in all organic food and as few artificial ingredients as possible. All in all, Chipotle seems the perfect restaurant: tasty, healthy, quick and well-priced. What’s not to like?

Since the first Chipotle opened in 1993, the national food giant has gained a loyal following of customers. The company has increased its number of locations each year, and now boasts 1900 locations worldwide and a market value of almost $24 billion. It has enjoyed double-digit sales growth for several years and a good reputation among health- conscious consumers. After going public in 2006, Chipotle jumped from an annual revenue of $628 million and 489 restaurants, to $4.1 billion a year, with approximately 1,800 locations in 2014.

Steve Ells, the founder, Co- CEO and Chairman of Chipotle, opened his first restaurant in Denver. The model, according to Bloomberg Business: an open kitchen, well-stocked with fresh ingredients, with cooking in the back and an assembly line at the front, to optimize efficiency and speed. The model has become “its own industry standard.”

Yet, recently Chipotle’s shares have plummeted, from $750.42 a share on October 13, 2015, to $463.57 on January 20, 2016. The company, with a $17 billion market cap, lost around $6 billion dollars in value from October 13 to December 7. Additionally, the company faces seven lawsuits.

Chipotle’s troubles started in July, when 5 customers contracted E. Coli in Seattle, The New York Post reported. In August, more than 100 diners developed norovirus in Simi Valley, California. Later in that same month and into September, 64 cases of salmonella were reported in Minnesota, stemming from 22 local Chipotle restaurants. In Boston, 80 Boston College students contracted norovirus in early December. Cases of E. Coli continued to crop up, and by December 4, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (the CDC) had reported 52 people, from 9 different states (California, Illinois, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania and Washington), infected by two separate outbreaks of the disease – Chipotle was responsible for both.

William Marler, however, a Seattle lawyer focused on food safety who represents 74 Chipotle victims, argues that there was probably a much higher number infected than 52. “For every one person they count, there are about 10 people who go to the doctor and don’t get a stool culture,” to provide concrete evidence of E. coli.

Matt Wise, a CDC epidemiologist, commented in an interview with Bloomberg, “The fact that these outbreaks don’t seem to be confined to a geographical region is harmful to the brand. Chipotles brand-perception problem has just gone coast to coast.”

The source of the E. coli came from somewhere in Chipotle’s supply chain. The culprit was most likely one of Chipotle’s big suppliers, since restaurants all over the country were contaminated. E. coli, spread through feces, is killed when food is cooked for an ample amount of time at a high temperature or suitably sanitized. Foods that are eaten raw, like tomatoes, lettuce and cilantro, are at the highest risk of contamination, but those are the same ingredients that give Chipotle its “fresh” and “natural” taste.

Some changes recommended for Chipotle could negatively affect this natural taste. Officials suggest that the company make more food ahead of time, at commissaries, where it will then be shipped to individual restaurants. Christopher Muller, a professor at Boston University told Bloomberg Magazine that Chipotle is in a tough spot, because “They want to have this local, fresh image, and making food in a commissary and shipping it all over the country takes away from that.”

Commenting on this struggle between local and safe, Chipotle’s CFO responded, “We like the local program, we think it’s important, but with what’s just happened we have to make sure food safety is absolutely our highest priority. If it’s testing and safety vs. taking a step backward on local, we would do that and hope it would be temporary.” Ells, believes that the company won’t have to sacrifice either. He says, “We’re doing both: great ingredients and the safest place.” But, Ells did reveal that eventually Chipotle may need to raise prices to “invest in food safety,” instead of just “food integrity.”

Meat is already prepared at central commissaries and tomatoes diced there. These changes just mean that more of Chipotle’s food would be prepared at these central locations, rather than in individual restaurants. Ells told Bloomberg, in an interview back in 2014, that the Chipotle assembly line is all about efficiency: “We all think…how do you do it faster? Throughput is something that we always will have to think about. Faster, faster, faster, faster.”

At some locations, Chipotle is able to serve customers in under two minutes, according to the restaurant consultant. This speed compares favorably to the four to six minutes at most fast-casual chains. Some things can get sacrificed in the name of efficiency, though. For example, every hour, an alarm goes off, reminding employees to wash their hands and put on a fresh pair of gloves. However, former managers admitted that the alarm was ignored when restaurants were busy.

The outbreak “has changed many people’s minds about eating there…Chipotle is working on a number of initiatives around food safety to minimize the risk of something like this ever happening again. Once they have implemented these new food safety practices, they will be way ahead of the rest of the industry and their competitors,” believes Wendy Smith, the general manager at Sequence, a company who handles Chipotle’s advertising. “I think people should continue to eat at Chipotle because by eating there you are supporting their mission to transform food production in the U.S., which benefits everyone. And when compared with many other fast food options, it is a much healthier way to eat.”

Although most people are focused on the dangers of bacterial contamination right now, Chipotle holds another surprise for it’s health- conscious consumers: calories. The executive VP at Technomic, a food industry research firm, told Business Insider that “the fact that they’ve convinced consumers that the product is healthy is incredible.” The New York Times found that the “typical” Chipotle order, (i.e. a meat burrito with beans, cheese and sour cream) contains a whopping 1,070 calories. That sum is surprisingly close to that of a fairly standard meal at a McDonald’s. According to the fast-food chain’s online calorie counter, eating a Big Mac, a medium order of fries, three packets of ketchup and a medium Coke means consuming 1,165 calories, just over that of the aforementioned Chipotle mean.

Meanwhile, a filling meal at La Taquería, one of the San Francisco Mission’s most beloved taquerías, of 4 meat tacos measures only 520 calories. Even a carne asada super burrito at La Taquería comes in at just 633 calories. Another potential health cause for concern at Chipotle is that most of the restaurant’s meals contain an entire day’s amount of FDA recommended daily amount of sodium, and 75% of a daily amount of saturated fat.

Although Chipotle markets itself as supporting a healthy lifestyle, patrons need to be careful and conscious wherever they dine. Cute cartoons and flashy, attractive ads don’t always mean safe or healthy food.