This spring, Lick-Wilmerding’s biannual course evaluation, known as the Student Experience Survey (SES), will be getting an update. Dr. Juan G. Berumen, Lick-Wilmerding’s new institutional researcher, is currently building the new and improved questionnaire. He plans to make a number of changes to address criticism from both teachers and students who have long had mixed feelings about how student feedback is gathered.

The SES is an anonymous online survey which students are required to fill out for each of their six to eight classes. Students answer a variety of questions about their experience in the classroom, and that data is then sent to teachers as an online report.

According to Randy Barnett, Lick’s Assistant Head of School, the survey is a tool that facilitates teacher growth. He says, “Our goal for adults, just like students, is to practice lifelong learning.”

From many teachers’ points of view, the survey has both constructive and ineffective elements. Andrew Kleindolph, the Tech Arts Department Chair, said, “What’s most helpful is the written responses. That’s when I get the most things where I’m like ‘oh, I’m going to change this about my class.’”

Ernie Chen, an LWHS math teacher, agrees, adding that the comments are most helpful “when students are able to pinpoint definitive and specific things that they like, don’t like or want to change.”

Beverly Boitano, who also teaches math at Lick, expressed the view of many teachers, saying “the SES is an opportunity for kids to tell me what they feel without having that personal conversation that they might not be comfortable having, so I think that’s valuable.”

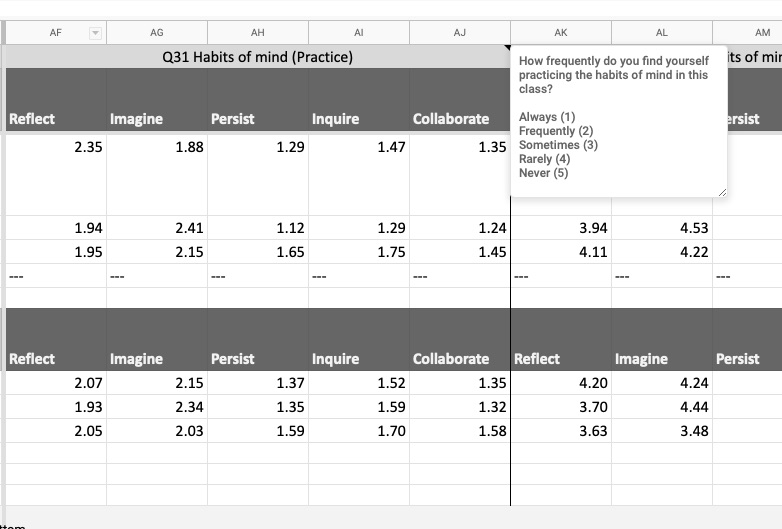

However, a number of teachers pointed out faults in the survey. Kleindolph, who, has talked to many teachers about the SES, said that a lot of them “don’t feel connected to the survey and the data.” He explained that some questions, such as those that ask students to rank the habits of mind, are not the most effective questions to ask. For example, he might see a lower score on his use of the reflection habit of mind due to the fact that a reflection activity might not happen every class. Kleindolph recognizes that a low score is not always a bad thing, but he says that the data can be hard to interpret. The survey feedback “requires someone who has a strong understanding of how to read the story in the data,” he said.

Even Chen, one of the Statistics teachers at Lick, says the survey is “statistically questionable.” Chen explains that a number of the survey questions provide students with a statement and give them options such as agree, disagree and strongly disagree. This type of question is called a categorical variable. The survey takes this categorical data, and assigns each response a number (a strongly agree might be 5 while a strongly disagree might be 0). When the results are presented to the teachers, they see a single number, which is an average of these responses.

Chen says there are two problems with this technique. Firstly, when a number is assigned to a statement such as “strongly agree,” it is quantifying something that can be interpreted in many different ways. The jump from “disagree” to “neutral” could be insignificant for one student and incredibly meaningful to another, but the computer will always assign a 1 to disagree and a 2 to neutral.

Secondly, “reporting an average is dangerous when you have a categorical variable” because a single outlier can skew the results. If one person misreads the prompt and submits a strongly disagree rather than a strongly agree, it disproportionately affects the results.

To avoid these problems, Chen has a few suggestions. One is that the survey could provide students with a slider from 1 – 100. In this way, students could quantify their answers themselves.

Or, if the question is kept the same, Chen suggests presenting the teachers with the percentage of their class that chose each response. This way, an outlier would not skew the data, and the teacher would receive more accurate information.

Raúl Betancourt, an LWHS chemistry teacher, brings up another critique of the SES. He cites an article from Inside Higher Ed which investigated the “mounting evidence of bias in student evaluations of teaching against female and minority instructors in particular.” “All the research shows that [these surveys] reveal less about learning and more about preference,” Betancourt said.

He mentioned that when students are challenged, they often become frustrated with the teacher, leading to harsh, unproductive SES comments. But from his point of view, struggling with the material leads to a deeper understanding, and to him, that sort of student growth is the most important.

Betancourt also emphasized the power of overtly mean comments, saying “for me, teaching is about relationships, and unkind words damage relationships.”

Negative feedback was something that all teachers had to deal with. Chen said that he always reads negative comments twice. “The first time I have a reaction, and I probably don’t read it with a clear head. The second time I know its coming, so I’ll read it more clearly,” he explains.

Barnett tries to make it clear to students that “the audience is their teacher.” He says that despite what some kids think, “the survey is not a way for the administration to find out who’s not doing a good job.”

Barnett says that if a student does have a problem with a teacher, they are encouraged to talk directly with that teacher. If they feel uncomfortable, they can ask an advisor or dean to be in that meeting with them. Barnett explained that “being able to speak to power when your experience is not solid” is an important skill.

Barnett normally only looks at the school wide survey results. But, in the rare case that he receives negative feedback directly from a parent or student about a specific teacher, he will sometimes check the results of that teacher. He does this to see whether the complaint is a recurring pattern in the class or if it’s just an outlier. Barnett explained that “there are times when a student might receive a bad grade for example, and then they externalize it and turn it into the teacher’s fault.”

Barnett also emphasized how the school has many ways of supporting students and teachers other than the SES. He mentioned Student Support Services or SSS, a group of adults on campus whose job is to help students that are struggling. “One of the big assets of an independent school, the bang for the buck for the tuition, is that we don’t let kids fall through the cracks,” Barnett says. “We have a lot of support systems for students, and ways of taking care of them.”

The Lick students interviewed were ambivalent about the SES. Natalie Keim ’21

expressed a common complaint, saying, “The monotony of the survey I think is frustrating to students. We are asked the same questions so many times year after year that it can be hard to feel compelled to give specific feedback.”

There is also a feeling among students that the SES incites very little change in the classroom. Mira Terdiman ’20 said, “After we fill out the survey, it seems like that’s the end of it. I think it might be more helpful for the students to see teachers making plans for how they are going to respond so that we feel like filling out the survey actually has an impact.”

Nevertheless, both Terdiman and Keim expressed their appreciation that Lick makes room for student feedback. “I think it’s really nice that we have the opportunity to give feedback to our teachers at all. And I think not every school gives students that opportunity,” Keim said.

Barnett recognizes that the survey is a work in progress. He says he is always tinkering with and improving the survey based on the community’s suggestions.

In fact, Barnett created the SES in response to faults with Lick’s previous teacher feedback system. This original form of teacher feedback, called course evaluations, required teachers to design their own paper surveys for students to fill out anonymously. Teachers then collected the forms, read them, and wrote a summary to their department chair.

Barnett found the course evaluations to be “a highly inefficient and really inconsistent process.” He added that, because the evaluations were completed at the end of the semester, it was “too late to do anything about the feedback.”

For this reason, Barnett rebranded the Lick feedback process, creating what came to be known as the SES. Barnett standardized the survey using the same nationally researched questions for all Lick classes. He also moved the survey to the middle of the semester, giving teachers more time to adjust to feedback, and, most notably, put the survey online, making the whole process more efficient.

This year, the school hired Berumen to administer the Student Experience survey. Berumen has a PhD in education policy, meaning he is trained to assess educational programs, curriculum and pedagogy (the method and practice of teaching). He also has a lot of experience improving academic programs, having worked with school districts, universities and even national programs.

Berumen plans to enhance the SES through four phases. The first phase involves talking to as many faculty members as possible to see what they like, don’t like, and want to change about the SES.

During this initial phase, Berumen learned that many teachers were giving their own surveys in addition to the SES in order to gather class specific data. This discovery inspired Berumen’s most significant alteration to the survey. He said that “instead of having those standardized questions that don’t really help a lot of the teachers make adjustments, what I want to have them do is submit their own questions.” Berumen plans to include both personalized and schoolwide questions in the new survey. He hopes that these course specific questions will make the surveys less repetitive, which is a common complaint among students.

In addition to the questions themselves, Berumen also intends to change how the teachers interact with the survey data. He equates his plan to Fantasy football saying “fantasy sports leagues have these really comprehensive dashboards where you can pull up a player and it gives you all of this data on them. I want to create student dashboards.” Berumen plans to include grades and attendance in these “student profiles,” so that teachers can see what is working for students who are “doing really well” and try to apply that to the whole class.

However, the surveys are currently anonymous. When asked how anonymity would factor into the dashboards, Berumen said he’s still unsure, but “If anything, at least the dashboard will have the SES results for the whole class.”

Barnett said the school would absolutely not violate student anonymity. In his vision of the dashboards, teachers would “be able to use identifiers such as ethnicity, zip code, gender, type of middle school and a few others to see if there are any trends around groups of students and not individuals.”

Barnett explained that only himself, Beruman, and Erica Obando, LWHS registrar, can access the student ID numbers which link students to their responses. Barnett said they would not do this.

The second phase of Berumen’s process will consist of actually making these changes to the survey. Berumen will also hold a workshop for teachers on how to create survey questions. “I know [this] sounds kind of nerdy,” he says, “but there is an art to designing good survey questions.”

The third phase will be beta testing the new survey this spring. For the fourth phase, Berumen will make even more adjustments based on feedback from phase three.

Despite the survey’s mixed reputation, it has allowed the school to recognize and address a number of blind spots in its approach to teaching. Eric Temple, The Head of School, offered an example, describing a correlation they discovered between the type of middle school students and how well those students adjusted to Lick’s academic demands. This information, Temple said, helped the school better support incoming frosh.

Temple adds that “there is a real thing called math anxiety, especially for our students who identify as women.” He explains how the survey allowed the school to see in which classes math anxiety was a problem and in which classes it wasn’t. They visited the classes with less math anxiety reported and said “Okay, what kind of practices are going on here and how can we implement these strategies in other classes?”