Contrary to the belief that the California School of Mechanical Arts (now known as LWHS) was founded as an all boys school, in its first iteration when it opened its doors in January 1895 both boys and girls walked in its front doors. One of the school’s pamphlets from 1896, the school’s second year, states that the California School of Mechanical Arts would be open to “any boy or girl of this state qualified to enter.” According to the same pamphlet, the first class to ever attend the school consisted of 106 boys and 30 girls, and the second had 75 boys and 50 girls.

While the school included girls, the experiences of the first girls who attended the California School of Technical Arts appears to have been distinctly different from their male counterparts. A second pamphlet from 1896 outlines the required courses for students: boys took carpentry, pattern making, forging, molding, machine shop practice and machine drawing.

Girls, however, took courses that would prepare them to occupy more traditionally feminine roles: cookery, dressmaking, art needlework, millenary, wood carving and modeling.

The only classes that were required of all students were technical design, architectural and mechanical drawing and college preparatory courses. Once girls got older, their curriculum narrowed to a much more home economics-centered education, with classes such as cookery, household art and the chemistry of cooking.

Despite the difference in classes, girls served in the student council alongside their male counterparts. The positions of treasurer and vice president were consistently held by women.

The girls, like the boys, were also involved in athletics. The girls had both swimming and basketball teams, although they lacked proper league games against other high schools teams and only played intramural games. Articles about the girls’ teams written by boys appeared in The Tiger, the newsletter. They praised the teams, supported their progress and highlighted star players.

The girls organized clubs such as the “Past Time” club which intended to encourage women to participate in extracurriculars. Each girl was motivated by the school to contribute to the community. They were required to partake in at least one extracurricular if they did not play a sport. Many participated in the debating club, and spirit club and coordinated school dances.

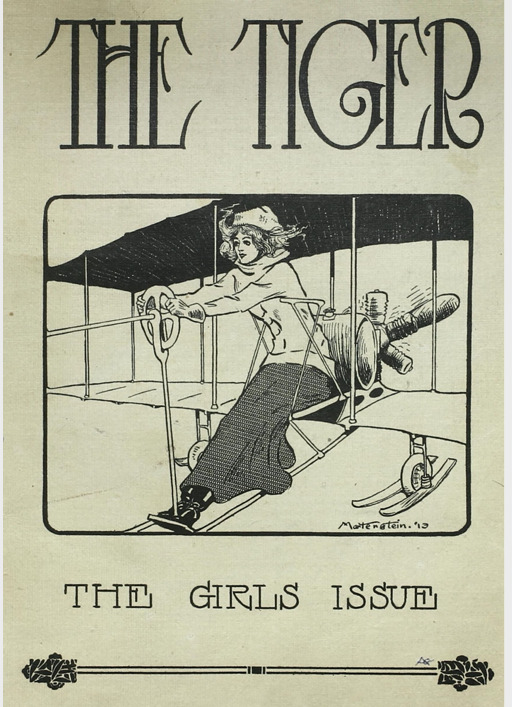

In 1911, The Tiger published a “Girl’s Issue.” The entire editorial and managing staff were women. The majority of the pieces in this issue were also written by women. Even in its youngest years, LWHS was providing a women-supporting-women space for them to amplify their voices. In this issue, a piece was written about the third annual Girls’ Rally which was led by girls and female teachers. The issue also features alumni who attended Stanford, particularly highlighting the women who did and their interests and accomplishments.

Courtesy of the LWHS Archives

After 18 years of girls at Lick, the Lick and Wilmerding Schools closed their doors to women when the Lux School for the Industrial Training for Girls opened in 1912. All the girls moved from LWHS into this all-girls school.

The mission of the Lux School, endowed by Miranda Lux just before her death in 1894, was published in an issue of The Tiger, for “the promotion of school for manual training, industrial training and for teaching trades for young people of both sexes in the state of California and particularly in the city and county of San Francisco.”

The Lux school included industrial arts classes: hat making, sewing, home economics and very basic regular classes such as Math and English. The Lux school was a sister school to the Lick and Wilmerding Schools. While each school had a separate building, they also shared classes and facilities. George Merrill, a noted educator and part of the industrial education movement, was the director of all three.

The Tiger had numerous “Girls’ Issues,” editions featuring news and writing from the Lux School. The school used the magazine as a platform for girls to publish their writing, including essays, poems and short stories.

In 1930, The Lux School changed its name to Lux School: An Institute of Technology for Girls and Young Women. In 1934, the school was renamed The Lux Technical Institute. In 1942, Lux separated from what had become Lick-Wilmerding High School in 1939, and became a Junior College program called The Lux College. After several years of functioning as a junior college, the school dissolved in 1953 “due to the embezzlement of funds,” said Marjorie Albarran ’54.

In the fall of 1973, Lick-Wilmerding High School finally invited women back into the school. At this time, all-boys and all-girls prep schools and colleges on the East Coast were also going coed. Phillips Andover Academy became coed in 1973, Yale College in 1969 and Davidson and Dartmouth Colleges in 1972. Columbia finally joined in the movement to integrate women into all-men’s colleges in 1989, although Barnard continued as well as an all-women’s college alongside a coed Columbia.

LWHS’s first coed graduating class (since 1911) graduated in 1975. Betty Schwartz Marcon ’79 recalls the conflicting sentiments caused by the re-entry of women into the school. She said, “it became apparent that there were some teachers who were definitely not ready for girls at the school. I think that many teachers were shocked at the level of scholarship that the girls brought to the school.”

Since LWHS did not have a girls’ soccer team when Marcon attended the school, she played, and was the only girl, on the boys’ soccer team. She described her experience on the team as “horrible.” “The boys did not treat me with respect, and I was a joke to them,” she said.

Sharon Clisham ’78, described how the early moments of coeducation played out in LWHS’s shops classes. She said, “Students had the option to take machine shop or jewelry shop. Women were advised to take jewelry shop; we were never really told why. But, I decided to take machine shop. I was the only girl, and the instructor was on my case all of the time.”

However, despite the harsh conditions women at LWHS faced, many of the first women to join the new coed iteration of LWHS view their high school experience as a positive one. Clisham said that her biggest takeaway from LWHS was self-confidence. “We were taught to be self-sufficient, and that’s something I really appreciate.”

Those ideals are instilled in many students, of all genders, today. Although sexism is still prevalent in American culture, the school equips students with the skills and confidence in their opinions to combat these issues.

As many know, recently there was a walkout against sexual assault and harassment led by and completely organized by students who saw a desperate need for change. The school also provides spaces on campus to encourage dissent, such as the Paper Tiger and “Girl Talk,” an annual event of girls supporting girls by sharing stories.

Teachers especially encourage women to take leadership roles and support the spaces for them to raise their voices, including LWOW, or Lick-Wilmerding Organization of Women. Classes such as the U.S. History Seminar — 20th Century U.S. Women’s History and the English Seminar on Gender Studies — offer important forums for exploration and learning. Texts used in all English classes present great writing, including great contemporary writing from authors of all genders.

The Math Department deliberately addresses sexist habits in group work and class discussions. “In some classes, it’s discussed explicitly when male voices feel more comfortable to speak and take risks. We hold the space to make sure that women also have the space and are invited into the conversation. We provide a place for female students to feel valued and heard, not only by the teacher but by peers,” said Math Department Chair, Annie Mehalchick.

Women, and students of every gender at LWHS, are recognized for their brilliance, intellectual power and creativity, for their collaboration and leadership. This is true schoolwide, community-wide. It is conscious, deliberate and normalized.

Yet, although LWHS has progressed in the equity with which people of all genders are treated in our community, there is always room for improvement. While sexism is present here, the school equips its students with the tools to make meaningful change.