Lick-Wilmerding High School has a homework policy in place intended to guide teachers in the amount of work they can assign their students based on the grade level of the class. However, this guideline tends to be ineffective because students are concerned about falling behind if they do not complete their work.

For most classes, teachers are officially only supposed to assign up to 45 minutes of homework to their students between classes. For honors and accelerated classes, teachers are allotted one hour.

Assistant Head of School Randy Barnett described what this over 15-year-old policy entails. In addition to providing a time guideline for teachers, the policy “identifies what homework is for, that it should be posted by the end of the day it is assigned, and that it should be explained in class, especially if the assignment is complicated,” he said.

Even when the policy was created, the school was aware of potential challenges the time limit. “You’re automatically going to have some variation just based on ability level in a certain area, ability to focus and in some cases, there are students who think that putting that extra hour into it will get a higher grade,” Barnett said.

The results from an anonymous student survey sent out in the eTiger showed some interesting statistics from the 90 students who responded across all grade levels.

40% of students who replied said they received the most homework from their history classes. The two classes that assigned the next most homework were math and science, with 16.7% and 15.6% of students reporting it as their course with the highest workload, respectively.

Regarding the time guideline for homework, the survey showed that 65.6% of students do not stop working on their homework if it is incomplete after the allotted time is up. Only 4.4% of students consistently do stop at this limit, and the rest said that their decision varies.

Siena Weisman ’25 said that the main reason she does not stop working on her homework after 45 minutes per class is that the work still has to be completed at some point.

“I’ve had it happen one or two times where I email my teacher and say, ‘This is what I got done,’ and they say, ‘Okay that’s great, can you do more tomorrow night?’” Weisman said.

For the low percentage of students who adhere to the policy word for word, most found themselves behind in that class if they did not complete their homework.

Antonia Casey ’23 described her reasoning for going over the time limit: “I really want to do well in my classes, and so I’ll do the work that is assigned without caring about the time limit. If I go over, I go over.”

Most students feel pressure to complete their homework past the time limit because they do not want to fall behind in class.

Gigi Torres, a math teacher at LWHS, described her thought process in assigning homework. “I would say the bulk of homework is practice for what we covered in class,” she said. Torres hopes that students “get a deeper understanding of the concepts we learned that day” in completing their homework before the next class.

Christine Wilkinson, a science teacher at LWHS, often assigns practice worksheets and finishing classwork as homework for her sophomore Chemistry class.

Wilkinson noted that her goals in terms of accuracy for homework assignments can sometimes be lost on students and cause them to be more stressed over homework than they need to be. “I want students to feel comfortable messing up on their homework, but I get nervous that that’s not how students see homework, as an opportunity to fail and have me help them and answer questions. It is never my expectation that they get 100% of their homework correct the first time they are trying to do it alone,” she said.

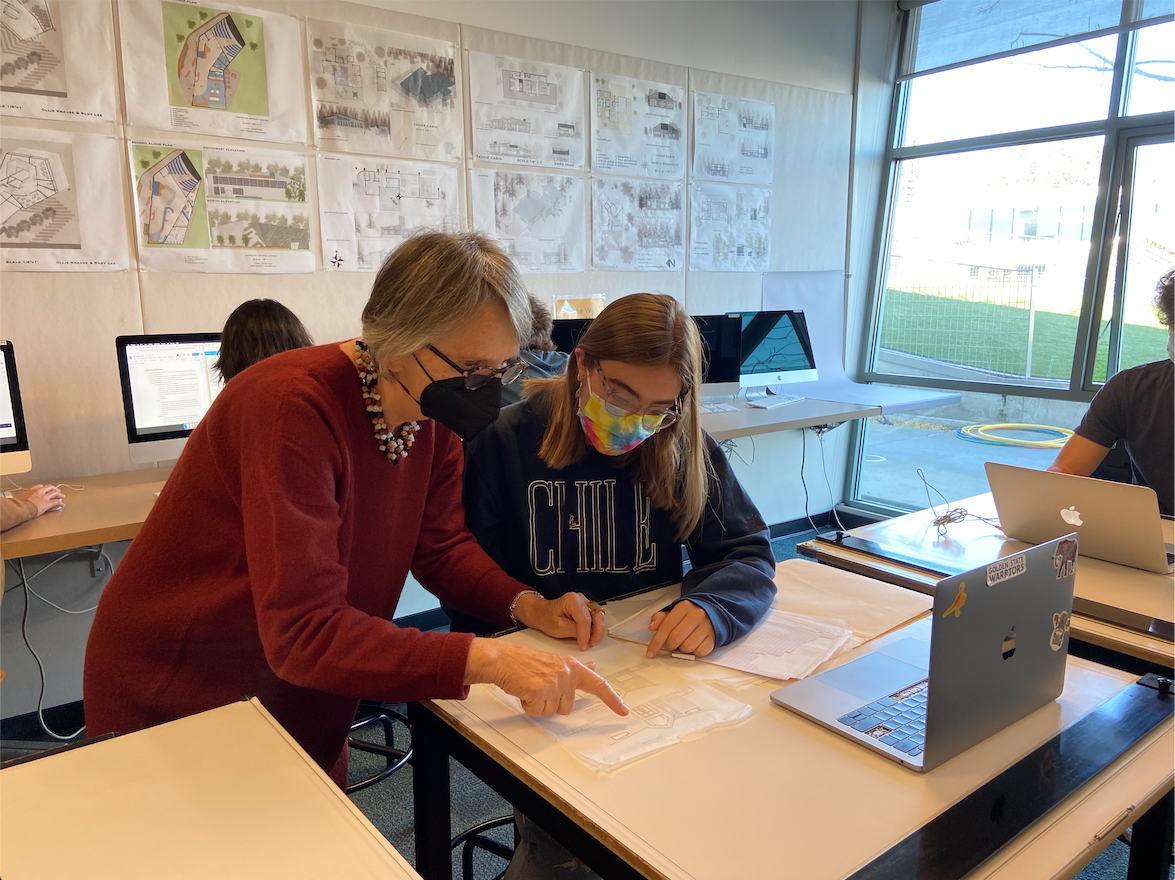

The purpose for assigning homework is a bit different for Architecture and Contemporary Media and Arts teacher Goranka Poljak-Hoy. Visual arts at LWHS are more project-based classes, so the amount of time spent on homework per night varies and is dependent on the student’s focus in class.

photo by Nina Laser

Poljak-Hoy described the challenges she faces in assigning homework for an arts class: “I never know if an assignment will take a student a full hour in design. It’s really hard to put aside projects when you enjoy doing something, and it’s hard to be able to tell students when to stop. Sometimes, I find that [students] are going into details that I would never even have imagined,” she said.

A recurring issue for teachers is assigning homework that adheres to the time limit is that every student works at a different pace, meaning that the amount of work that takes one hour for one student could take another student only half an hour, and another student a full two hours. One way they try to combat this issue is through regular feedback forms for students to be able to communicate how long they are spending on homework.

Wilkinson’s response to feedback is to adjust the amount of homework she is assigning and to keep sending out those surveys until it seems like she has hit the target amount of time spent working — at least for the majority of her students since there is always some sort of variation.

“Sometimes I follow up with students and ask questions such as ‘how long do I think this should take you versus how long it actually does,’” Wilkinson said.

This is an important question to ask, especially because the fine print of the homework policy itself states that the time guidelines are for uninterrupted, focused work. If a student is counting all of the time they spent texting friends, talking to family or watching TV while doing their homework then the time it took them is not an accurate representation of the amount of work assigned.

“You’re not going to gain anything out of doing the work if you’re not really focused and paying attention,” Torres said.

Another important thing to consider is that the homework guideline “is meant to be a ballpark figure,” said Barnett, meaning that it is to be expected that homework will be a bit longer some days.

While ideally if a student is consistently going over the allotted amount of homework time for a specific class, they would be able to directly communicate with their teachers about it, more often students will go either to their advisor or grade level dean.

The dean for freshmen and sophomores is Christine Yin and the dean for juniors and seniors is Kindra Briggs.

Yin and Briggs both are happy to support students in finding a good balance for homework but wish that more students would communicate directly with their teachers and even be able to ask the purpose behind the homework.

“Students and parents often come to me with questions about workload, about how long it should take, to share that it is taking too long, or that they aren’t getting enough sleep. My question in response is always what have you communicated with your teacher? In most cases that is enough, just having that conversation,” Yin said.

If it does appear to be a pattern, then sometimes the deans will strategize with teachers about it, but even at that point it’s still a conversation and not an intervention.

According to Briggs, the process usually includes brainstorming “what strategies the department chairs or teachers can utilize in order to rethink the scaffolding of homework if it’s feeling overloaded.”

“Students will often take a skill from one class and apply it to the next one, but that doubles the time, because a different skill is needed for that class. Sometimes it’s about reminding the teacher to tell the students that they need a different skill set,” Briggs said. This point goes back to the idea that the issue is often students wanting to do well in class, and sometimes they do extra work that the teacher does not expect from them when assigning the homework.

Finding the right amount of homework is a difficult task, and one that is dependent on the cooperation of students and teachers. To achieve the target amount of homework, students must be honest and proactive in communicating with their teachers about how long the homework takes, and teachers need to be willing to hear that feedback and adapt.

The most important thing is that students and teachers at LWHS trust each other and build a foundational relationship so that communication can be direct and clear, teachers are able to cover all the course material, and students can feel less stress over a heavy workload. The policy is in place to encourage these kinds of behaviors but was always intended to be flexible and adaptable instead of a strict rule.