From academics to extracurriculars to spending time with friends, Lick-Wilmerding students tend to have a lot on their plate, so how does the PPP program create space for service?

PPP stands for Public Purpose Program. This program is currently structured as follows. During freshman year, students take part in four service learning workshops which include discussions about social justice issues as well as hands-on volunteering experiences. As sophomores, students must complete forty hours of volunteer work. Finally, juniors and seniors may either enroll in a PPP class, design an independent study, work as an intern at a local nonprofit, or help develop curriculum for the freshman workshops.

Lick teachers also play a role in the program and are required to either teach a PPP class, chaperone a sophomore service trip, or lead one of the freshmen PPP workshops.

In order to get a well -rounded perspective on the program, it is important to know how it came into existence.

When PPP director Alan Wesson Suárez started working at Lick-Wilmerding in 2012, public service was a much smaller part of the school’s curriculum. Every year Lick scheduled a week of service work. This week, called Jellis Block, was named after Jellis Wilmerding, who founded the Wilmerding School of Industrial Arts.

During Jellis Block, each advising would delve into a specific social justice or community issue. Wesson Suárez explained that because each advisor designed the Jellis Block curriculum for their own advising, there was significant variability in the level of community engagement amongst the different groups. “It was based on the advisor’s excitement and advisees being into it,” Wesson Suárez said. “You had some groups who were connecting with different non-profit partners and meeting other people in the community, and then you had some who just watched a movie every day of the week.”

Part of the reason for this inconsistency was that advisors often struggled with the Jellis Block programming. Many found planning a week of social justice work to be extremely difficult, and at that time the Center provided little support. The school community — teachers and students alike — were largely unsatisfied with this service model.

When Wesson Suárez and Director of the Center Christy Godinez applied for Center job positions, the school was already considering rethinking the program. “It was good timing to transition to something new,” Wesson Suaréz said.

The first step in constructing the new program was to examine models of service teaching from various high schools and colleges across the country and discussing what elements from those successful programs could be reproduced at Lick.

Tulane University’s service program inspired one of the central pillars of the PPP program: choice. At Lick, sophomores get to choose how to spend their forty hours while juniors and seniors pick from a number of different PPP classes. Wesson Suárez explained that although this “makes for a lot more moving pieces, it ultimately has a better chance of a student landing on something that they really care about.”

Student engagement is very important to Wesson Suárez. He explains that “making people do something they really don’t care about or want to do feels like a waste of time.” In order to optimize student interest, the Center is very attuned to student feedback. They are constantly modifying the PPP program and finding new ways to foster meaningful connections between students and the community.

Head of School Eric Temple explained that another pillar of the new PPP program was the combination of service learning and curriculum. “If you can learn about a subject and do service as part of that, there is just a more intimate connection to what you are doing,” Temple said. This merger of traditional class work and service learning became what is now known as PPP classes.

Huezo.

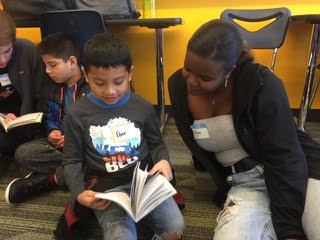

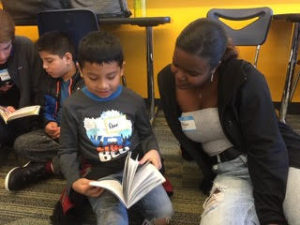

photo by Ivonne Hernandez

Ivonne Hernandez, who teaches Spanish 3 PPP at Lick, has found numerous ways to combine language learning and service. Five years ago, Hernandez’s class became part of the PPP program after they began writing stories for students at Centro las Olas, a Spanish immersion preschool in the Mission. In another one of Hernandez’s PPP projects, her students exchanged letters with Guatemalan students who were training to be bilingual secretaries. In addition to these letters, students would hold video conferences in which they shared different aspects of their culture.

These initial projects inspired Hernandez’s current PPP focus: working with first and second graders from Cesar Chavez Elementary. Lick students visit the little kids and help them work on their reading. In turn, the kids engage Lick students in spontaneous conversation and exchange monthly letters with them. This relationship culminates at the end of the year when the Lick students write each first and second grader a fictional story based on their requests.

Hernandez said, “Students in my class get to see Spanish as a communication tool that is essential to connect with those who speak it. For me, it’s so important to be able to communicate with others using their native tongue because that connection is priceless.”

However, not all PPP classes are equally engaging. Wesson Suárez said that increasing consistency across PPP classes is a major goal of his. “I’m trying to figure out a way that a student could end up in any class and definitely have an experience that they find memorable,” he said.

The experience of Colin Rushing ’22 speaks to how different PPP activities can inspire varying levels of enthusiasm from students. Rushing explained that while working on his 40 hours of service, some activities, such as translating letters from Spanish to English for Guatemalan women, were quite meaningful, while others felt almost like busy work.

Indigo Mudbhary ’22 felt that the freshmen year workshops were lacking in complexity and information. “I feel like they just need to restructure it, because it could be something great,” she said. She explained, for example, that “gentrification, which we learned about, is a complex issue, and they were just repeating over and over again one specific take on it. Though I agreed with that take, it was difficult for kids who didn’t agree with that and didn’t feel safe to actually have an educated discussion.”

photo by Ivonne Hernandez

Nevertheless, Mudbhary was extremely excited about all her sophomore year volunteering. “I’ve worked at the Asian Art Museum and a pet food bank. I volunteered at an orphanage in Nepal. I’ve worked at some food kitchens. I’ve helped tutor some kids in my neighborhood. It’s been really gratifying, really meaningful,” she said.

Wesson Suárez has three overarching goals for the PPP Program: creativity, that students are able to think in a nuanced way about issues facing their communities; curiosity, that they are aware of those issues rather than ignorant of them; and compassion.

The biggest challenge that Wesson Suárez faces when organizing the PPP program is time. “American culture in general is too busy, there’s a lot of demands on one’s energy,” he explained. “One of the challenges is to slow down enough to be able to learn about different issues and different people and to be able to engage meaningfully.”

Brandon Moore ‘20 said, “During my junior and senior years I took a French and English class, both PPP, and while you do learn a lot about different cultures, it’s also overshadowed by the more academic sides of the program.”

To improve the program Moore suggests “something more regular and more focused on purely PPP.”

Across San Francisco, there are many different approaches to highschool service learning. Similar to Lick, both the Urban School of San Francisco and San Francisco University High School begin their programs in freshman year, requiring students to complete some sort of curriculum which covers general themes of civic responsibility and social justice. But from sophomore year on, each school offers a unique path.

University students focus on developing a strong relationship with one specific organization. During the first semester of their junior year, everyone chooses from a range of social issue courses such as Equity in Sports, Education, or Racial Injustice. Then, in the second semester, they volunteer at an organization that relates to their social issue course. The whole program culminates with a senior year community engagement project.

University High School junior Micheal McKane found his social issues course, which centered around religion, to be very interesting. McKane, who is Catholic, said that before the course, his faith was dwindling. He had heard a lot about the negative impacts of religion, but the class exposed him to the positive side of his faith. “It’s all about how you interpret it,” he said. “Religion can be a pro or a con when it comes to social justice.”

McKane then began volunteering at his church to fulfill the junior year service requirement. “The experience has helped me become more committed and more faithful,” he said.

At Urban, discussion and classroom learning are two big themes of the service program. Each year, Urban students take a six to eight week course on topics ranging from identity and ethnicity to inequity and resistance. Starting in sophomore year, students partner with an outside organization and begin volunteering outside of school as part of the program.

Urban junior Samuel Levine said that he has enjoyed partnering with the The Lantern Center, a group that offers education to immigrants. However, he has a few critiques for Urban’s service learning class. Levine explained that Identity at Urban and Beyond, the course which he is currently taking, oversimplifies the concept of identity.

When reflecting on PPP as a whole, Temple said, “I do think, as humans, it is important that we know the world is more than just us.” He added that “when we volunteer, we feel better about ourselves. And for kids going through adolescence, which is not the easiest time in anyone’s life, that can feel pretty nice.”

“I don’t want to think of it as a perfect program,” Temple concluded. “But I’m glad we have it.”