A short ride between BART stations can mean an 11-year difference in life expectancy. This statistic is mentioned in the summary of BlendEd’s Public Health and Vulnerable Populations course and references the 73-year life expectancy of residents near the Oakland City Center BART station compared to the 84-year life expectancy of residents near the Walnut Creek BART station. In other words, living just 16 miles apart in the Bay Area can be the vital difference between two populations’ projected lifespans. But what does this really mean, especially in the context of the Lick-Wilmerding High School community that draws from all over the Bay Area?

The Public Health & Vulnerable Populations class is a semester-long course that focuses on answering the question of why prominent health disparities exist in the Bay Area, and what factors influence these discrepancies. Students learn how social determinants of health affect the lives of those in various Bay Area neighborhoods.

The existence of health disparities in the Bay Area is not a new phenomenon, nor is it uncommon knowledge. The Bay Area has the highest income inequality in California, which directly impacts the divergence of the region’s public health. These health disparities affect people from all neighborhoods, not just those who live in the Tenderloin or Hunters Point.

When the Public Health and Vulnerable Populations class was first created for the BlendEd Consortium, conveying this information to students was exactly the goal that Don Rizzi had in mind. “There is a place on that health-wealth gradient for all of us, and the class is meant to help people understand where they are on that gradient and what privileges they have. And certainly on the other end of the spectrum, privileges that are lacking for some of us that all go to the same school,” he said.

The BlendEd program was created in 2013 with the initiative of offering alternative elective courses to students that blended in-person learning with online learning, while utilizing the resources located in the Bay Area. Rizzi was one of the founding members of the program, along with several other Bay Area independent school educators. Today, the consortium is composed of students and educators from several Bay Area schools including The Athenian School, The College Preparatory School, Marin Academy, The Urban School and LWHS, among others.

The initial class spearheaded by Rizzi, that would later evolve into Public Health and Vulnerable Populations, underwent many stages of revision. It began as Race, Place, and Toxics from 2014-2016, then Environmental Justice from 2016-2018 and finally Public Health and Vulnerable Populations from 2018 to present.

As the BlendEd program grew, so did the number of students enrolled in the course. In the 2014-2015 school year, there were five students enrolled in the course out of the 84 students in the BlendEd program. Currently, during the 2022-2023 school year, there are 17 students in the course out of the 189 students enrolled in the BlendEd program.

To Rizzi, the most important aspect of the class is exposing students to different neighborhoods and communities that they have likely never interacted with before, specifically those adversely affected by the health disparities in the Bay Area. “I feel a responsibility to get people out of that independent school bubble. We go to our homes, which may or may not be in a well-maintained neighborhood, and we ride BART to school, so we’re kind of in this bubble to and from school. Having folks from Marin, Danville and San Francisco come together and walk around some neighborhoods that maybe they’ve never heard of before, and in many cases have never visited before, is really rewarding,” he said.

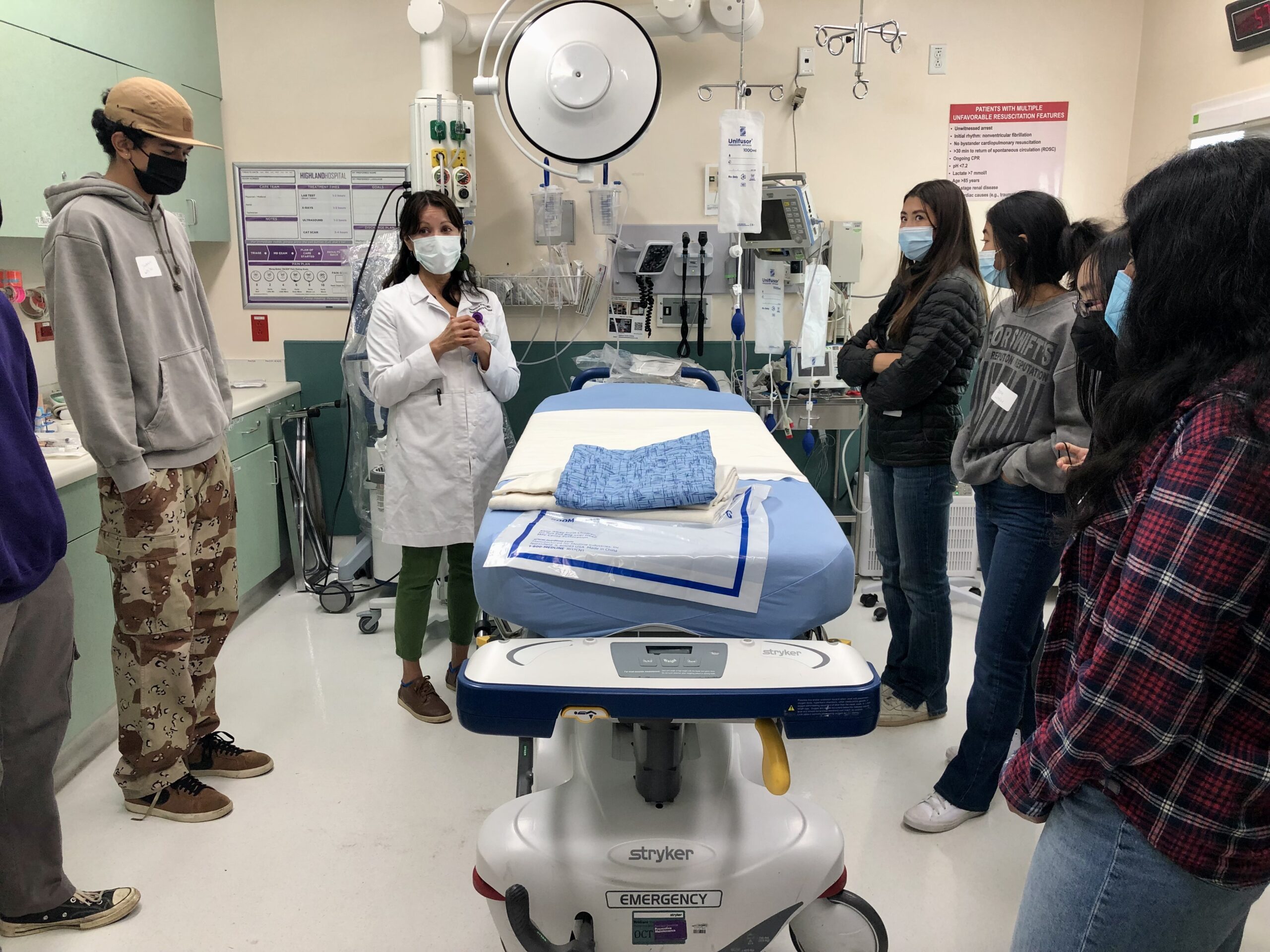

Lori Hébert, director of BlendEd, agreed. “A really important ingredient of BlendEd is those face-to-face field learning experiences. Public health is a great example of being outside of the classroom and learning in the streets of San Francisco…from doing the walking tour of the Bayview Hunters Point neighborhood, or getting out of the classroom to meet with an emergency room doctor and talk about public health issues,” she said.

To understand why health disparities exist, the class takes an in-depth look at the social determinants that contribute to the well-being and health of individuals in a community. Over the lifespan of an individual, these social determinants of health have been shown to be the most important contributors to the health of an individual.

The social determinants of health are factors such as employment, the walkability of one’s neighborhood, vocational training, access to healthy food choices and community support systems. The quality of the social determinants of health available to individuals often depends on their level of education, occupation, social class, gender, race and ethnicity.

Fernanda Sanchez ’23 took the class in the 2020-2021 school year. “What stuck with me the most is as someone who’s a person of color, we talked about the disparities in low-income neighborhoods and how that affects people of color the most,” she said. “Our health and the way we contribute to the earth affects people of color. But it’s something that’s barely talked about, and it’s the way that the government runs. It’s always putting the oppression onto people of color.”

In the U.S., a lack of investment in the social determinants of health has led to a disproportionate expenditure in healthcare without a proportionate increase in the health of the population when compared to other developed countries. In 2015 the U.S. spent 17.1% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on healthcare, a shocking leap from the next highest spender, France, with 11.6% of its GDP invested in healthcare. Yet, the U.S. ranks 30th in life expectancy, despite spending the most money per capita on healthcare than any other country in the world.

The reason for this largely points towards a lack of investment in social services such as housing assistance, food aid and child support. Medical experts are increasingly coming to the conclusion that these social determinants of health affect long term health more so than episodic healthcare visits.

Rizzi notes that important factors of health are given considerably less attention in the U.S. “When we say we want people to be healthier, most people will say universal healthcare and that is a part of the picture, but equal access to education is a health-related issue, access to reliable transportation is a health-related issue, so the goal is really just to expand peoples’ vocabulary when they talk about health equity and what can actually be done,” he said. “Certainly we should talk about healthcare, but if that’s all we’re talking about, we’re missing the large majority of what actually determines whether or not someone lives a healthy life.”

This social aspect of health is a heavy focus of the Public Health and Vulnerable Populations class, especially through an interactive lens. The class takes three field trips throughout the semester; to the socially disenfranchised community of the San Francisco Bayview-Hunters Point neighborhood, the Literary for Environmental Justice native plant nursery and the Emergency Department and Trauma Center at Highland Hospital in Oakland.

Zoe Yang ’23 recalls the trip her class made to the Bayview-Hunters Point neighborhood during the 2021-2022 school year. “I remember stepping off the bus and actually it was a very welcoming place. There was a fair going on, kind of like a farmers’ market, but it was actually really cool. There was music playing and it just wasn’t what I pictured for that specific area,” she said.

What is the significance of LWHS students experiencing varying levels of public health within communities? Dr. Erik Anderson, an attending physician in the Emergency Department at Highland Hospital who has a background in Population Health and Social Emergency Medicine, highlighted the importance of youth being exposed to the health inequities and the values it teaches. “High school students are the next set of health professionals. Going into this career, whether it’s as a physician, a nurse, a public health researcher or a scientist, remembering what those values are is really important. Trying to keep a focus on what drives you and what you think is important is not only what will make you happy, but will really help to address disparities and make the world a better place,” he said.

A wealthy independent school such as LWHS may be assumed to be uninfluenced by health disparities present within its broader community, but simply living in the Bay Area is synonymous to having a place on the health-wealth gradient. As a school that strives to achieve a diverse student body through representing dozens of zip codes, LWHS reflects the diversity of the Bay Area’s living experience far more than many other independent schools.

Yang praises the school for fostering a community in which a student is not defined by the area they live in. “Lick does such a great job in making sure that those disparities from someone’s outside life don’t conflict with their life at Lick. But because Lick pulls from all these diverse neighborhoods and all these geographical locations, there’s going to be differences within those neighborhoods. Lick strives to create a space where those differences don’t matter as much,” she said.

Health disparities are an issue that exist far beyond the scope of the LWHS community or the Bay Area community. The data from the past couple of decades conveys that the wealth gap and the differences in public health are only growing further apart. However, the Public Health & Vulnerable Populations class exists as proof that it is not an issue going unnoticed or uncared about.

Anderson suggests that one of the most important aspects of discussing public health is maintaining hope. “We have to remember that people will get better. At Highland, we see people who have had really rough lives in difficult circumstances. If we can do good, appropriate care for people, you’ll see them get better. When that happens, it’s amazing to be able to give a patient a hug after they’re reconnected with their family and are working again,” he said.

As of the 2022-2023 school year, the Public Health and Vulnerable Populations class is in its ninth year of enriching students’ understanding surrounding environmental injustice and allowing them to view public health through a more compassionate and humanized lens.