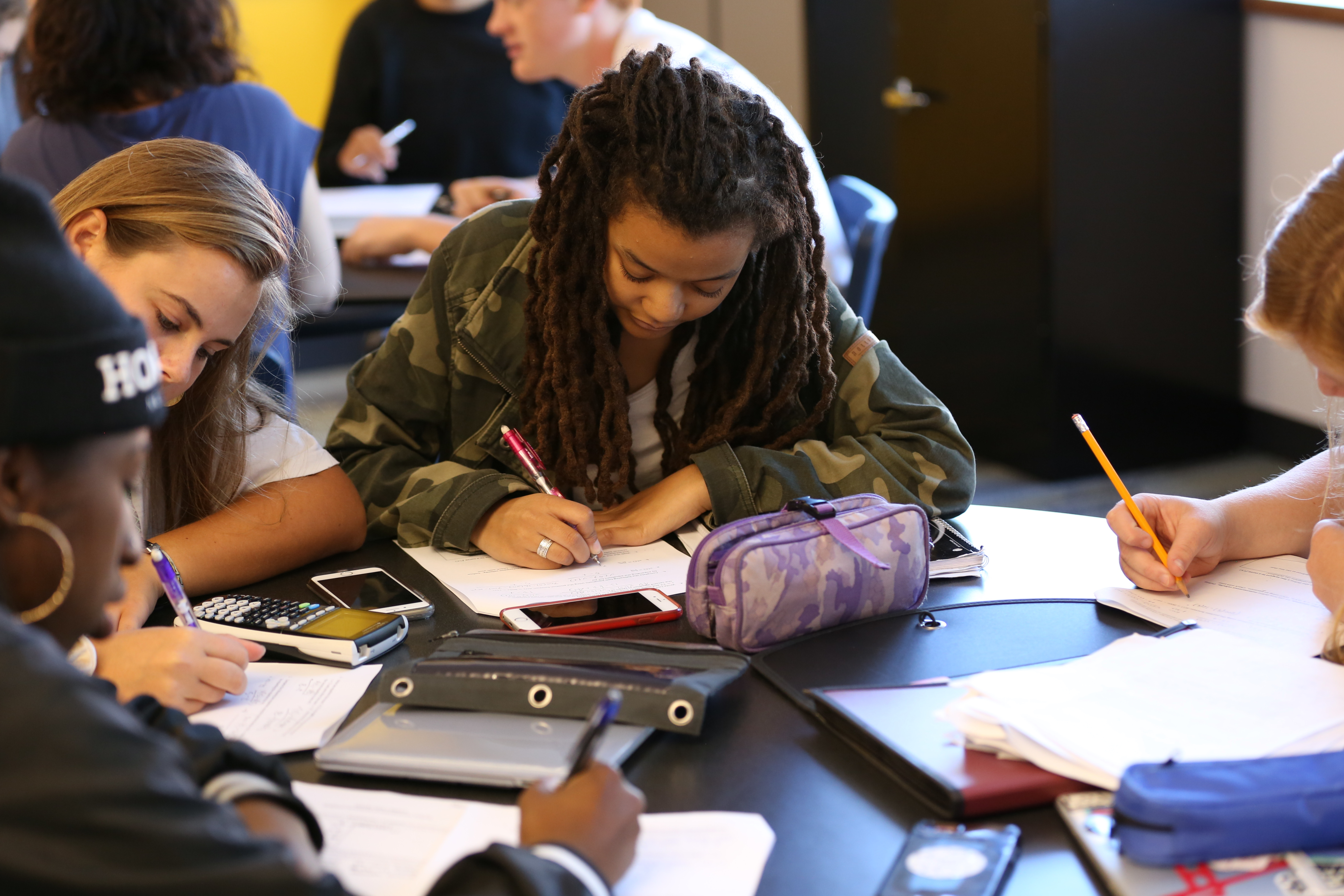

Walking into any Lick-Wilmerding math class, the culture of collaboration is unmistakable.

Signs that read “Math Is About Connections And Communicating” and “Mistakes are Valuable” frame long white boards covered in formulas and practice problems. Students sit around circular tables, asking questions, explaining their work and exploring each problem in depth. As teachers check in with each table, voices fill the room, each one louder than the next.

But in Lick’s honors math classes, as in many high school classrooms across the country, the loudest voices are often male.

Despite progress made in the last several decades, women are still less likely to reach high level positions in the field of mathematics. In 2018, the College Board reported that while 56 percent of all AP test takers were female, only 42 percent of BC Calculus test takers were female.

High school statistics translate to college and the workforce. In 2014, only 29 percent of mathematics students at the doctorate level were women, and only 15 percent of tenure-track math positions were held by women, one of the lowest rates among the sciences. According to Scientific American, gender differences tend to be larger — and develop earlier — among higher-performing students.

Lick is aware of these trends, and tries to take action by emphasizing collaboration: by seeking teachers committed to promoting group work in the classroom, they highlight teamwork when hiring new faculty to the math department. They discuss the growth mindset with each other and with students, teaching cooperation and growth in addition to mathematical concepts.

Their efforts shine through. At the beginning of the year, each class sets their own principles — or “Class Norms” — to guide collaboration and respect, which teachers work to uphold throughout the year. Classes often revolve around explorations that build from previous lessons; students work in groups to develop genuine, deep understanding.

“Part of the culture we have at Lick is to work in teams,” Annie Mehalchick, the Head of Lick’s Math Department, said. This environment comes down to details: rooms are designed to establish a collaborative learning style.

Alice Grimm, who teaches Inductive Geometry and Precalculus, agrees that collaboration should be integrated into the format of each class: “The less formal structure you have, the more the informal hierarchies of society will insert themselves, whether that’s around race or gender or whatever that is, because those are going to be our defaults.”

Despite Lick’s efforts, however, gender disparities remain visible in Lick’s math classrooms. In the 2017-2018 school year, there were 59 students in Algebra 2 Accelerated (A2A): 28 boys and 31 girls. This year, however, only 20 girls continued on to Lick’s Precalculus Honors classes, a 35 percent drop, while 28 boys continued on or joined the honors track. In the past, there have been honors math classes with as few as two girls. In conversations with dozens of young women, a pattern becomes clear: no matter how much teachers try to promote collaboration and inclusivity, students often fall short.

When Ari Gonzalez Silas ’20 placed into Deductive Geometry as a freshman, she didn’t think she would continue on the honors track for all four years. She fell in love with math at Lick.

“It’s exciting when you do well, and exhilarating when you figure something out, and satisfying and also devastating and frustrating,” Gonzalez Silas said. “Math for me is really empowering in that way because I feel like there’s always something I can do to further understand, to get better, to learn.”

Her A2A class was structured so that people chose their own groups, a system that Gonzalez Silas thinks promotes learning. “You work with someone who you already work well with; you work with someone who thinks the same way you do,” she said. But in her Precalculus Honors class, tables are assigned randomly, and students don’t have a choice about with whom they work.

When working with some boys, she’s noticed a visible difference between how they interact with her versus their male friends. “[Boys] flip a switch and they’re like, ‘Okay, I’m working with a girl,’” Gonzalez Silas said. “You can see it.” In her experience, the tension is made worse in classes where she can’t chose her table group and the collaboration feels forced. While the students may have been laughing and having fun, she can feel friction set in as she sits down at their table.

Elizabeth Ouyang ’20 also loves math, and has since middle school, where she took classes after school to get ahead of her classmates. But she remembers a unit in her sophomore year A2A class where she sat at a table with three boys. “It was really hard for me to ask [them] for help, and every time I would, usually [they] would not have the patience …or disregard my struggle,” Ouyang said. “[The boys] just wanted to one-up each other. By the end I just didn’t want to ask them for help anymore.”

Her experience profoundly changed her attitude towards math at Lick: when girls in grades below her tell Ouyang about their plans to take A2A, she warns them that the already challenging class is made worse by the gender dynamics. “I tend to shy them away from [it], like, ‘Don’t take it because it’s the worst thing that you’ll ever experience,’” she said.

At Lick, it’s not uncommon for both male and female students to feel impatient with classmates who may be struggling, including boys. But when this attitude is layered with gender stereotypes, it can disproportionately impact young women.

Jordan Hebert ’19 has seen the same behavior in his own honors math classes. “There is definitely an issue when a few people are working fast at a table and a slower worker gets left out,” Hebert said. “I’ve experienced being the slower worker at times and just being completely lost in class.” He said that those experiences interfered with his learning and lowered his self esteem.

Catharine Paik ’20 remembers how, in the middle of a disagreement with a male tablemate in her freshman year Deductive Geometry class, he cut her off as she explained her answer. He then turned to the rest of their table without taking her seriously.

Paik’s answer was correct. But when she confronted the boy who had ignored her, he wouldn’t admit that he was wrong.

“He didn’t give me the chance to explain myself, and then on top of that, he wouldn’t even let me explain why he was being rude,” Paik said. This experience proved to be emblematic of her experience in Lick’s math classrooms, she said.

This year, Paik is taking Precalculus in the standard math track, and has noticed that impatient and patronizing behavior is not as prevalent. “In Precalc, the mentality is a lot more about staying with your group and making sure that you’re all together,” she said. “…That’s an idea that the teacher in Precalc Honors tries to perpetuate, but I think it also sounds like the kids don’t really utilize it.”

Alumna Larissa Chan ’13, who recently graduated from John Hopkins University with a degree in biomedical engineering, remembers feeling frustrated about being silenced when it took her longer than her Lick classmates to grasp concepts. But the few times she experienced impatience were greatly outweighed by the success of Lick’s STEM program: she attributes her accomplishments to the variety of STEM themed courses, including technical arts courses, which fueled her passion to pursue engineering and design. Working through math problems with classmates, a system encouraged by teachers, helped Chan develop a deep understanding of and passion for the material.

“I owe my success in math classes at Lick to collaboration with my peers and investment from my teachers,” she said.

Many girls interviewed for this story say they are keenly aware and frustrated by a male-dominated environment, in which “mansplaining” (when a man explains something to a woman in a condescending way) and other rude behavior can be common. The boys in these classes, however, are often blind to the problem.

Girls say it’s uncomfortable — and not necessarily the girl’s responsibility — to call out friends and classmates. But when mansplaining and other sexist behavior isn’t brought to boys’ attention, it often gets swept under the rug, perpetuating a disconnect between how girls and boys perceive the same class.

Gonzalez Silas remembers how encouraging it was when her A2A teacher Ernie Chen called out a boy who was mansplaining her. She finds it hard — even scary — to risk being yelled at or belittled for calling someone out on their behavior. But when her teacher did it for her, she described it as empowering.

“It was such a relief,” Gonzalez Silas said. “…It’s a man, a grown man, who is a role model for this other person going, ‘Hey, that’s not how we do math together, that’s not how it’s going to work in this space.’”

“It’s crazy to think that it’s 2018 and I’m still talking about gender,” math teacher Yetta Allen said. Her “big wish” is that students of all genders would value learning more than grades, and she believes that more people would stay in the honors track if this were the case. While teachers have always tried to focus on depth over breadth, she said, she still thinks that the accelerated track caters to fast-paced learners.

Allen says empathy is key: “One of the strategies that I think is important is for people to have compassion, to understand everyone else’s struggle.”

Mehalchick tries to stay attentive towards every students’ behavior and needs in her Inductive Geometry and Calculus Honors classes, no matter what gender. “I try to be aware of who’s speaking, who was making assumptions of who can speak when, how people are being invited into conversations to share their ideas,” she said.

She doesn’t think that gender is the only factor that plays into which students chose the advanced math track, but as the Head of Lick’s Math Department, she said she’s dedicated to making a change if a gender gap widens.

Gender isn’t the only issue in honors math classes: as Lick tries to improve the advanced math track, it is imperative that all marginalized people are considered, especially people of color.

“The most egregious sexism I have seen has been directed against women of color, and I have seen Black and Brown men have their intelligence, competence, and expertise all questioned in ways that are often more extreme to what I have seen directed against white women,” Grimm said.

“We are a learning community, and therefore everyone has a right to an environment that is conducive to their learning,” Allen said. “And when you create an environment that is not helpful, then that behavior has to be corrected.”