By now, you’ve probably heard of Tiger King. Since the documentary series’s release on Netflix on March 20, tweets, memes, and comments have flooded the internet about the crazy stories of big cat (tigers, lions, leopards, panthers) breeding in the United States. The show is ranked number one on the Netflix trending list as people across the world bingewatch the seven episodes.

Throughout the series, Joseph Maldonado-Passage, better known by his stage name, Joe Exotic, struggles to keep his Oklahoma roadside zoo open. Along with caring for the 200 big cats at his private park, Exotic makes music, such as his country single “I Saw a Tiger,” stars in a web series about the zoo, and travels across the country to perform magic shows with his animals.

In the series, what takes up most of Joe Exotic’s time, however, is fighting animal rights activists. His extreme measures led to an FBI investigation. He was arrested for his involvement in a murder-for-hire plot to take down Carol Baskin, the owner of Big Cat Rescue, an animal sanctuary outside of Tampa, Fla. Exotic had been threatening Baskin

for years and was accused of paying someone $3,000 to drive from Oklahoma to Florida and shoot Baskin as she pedaled the course of her daily biking trail. Exotic was recently convicted for his effort to murder Baskin and sentenced to 22 years in prison.

Eric Goode, one of the directors of Tiger King, followed Exotic for five years, documenting the twists and turns of his day-to-day life. Goode, who produced Tiger King as the first documentary for his company Goode Film Productions, was supposed to be focusing on themes of animal welfare and environmental issues. The story of Joe Exotic and his world of big cats was conceived as a story about animal abuse and conservation. However, that story was overwhelmed. Netflix lists Tiger King as a true crime docuseries.

With a true story that seems almost too crazy to be true, it makes sense that viewers are obsessed with Tiger King. No writer could dream up the stuff in Tiger King or Joe Exotic himself — or the other characters.

With his persona of Joe Exotic, Maldonado-Passage assumes the role of a “redneck,” a derisive epithet used against working-class white people, typically from rural communities

in the South, which tags them as ignorant, prejudiced and outlandish.

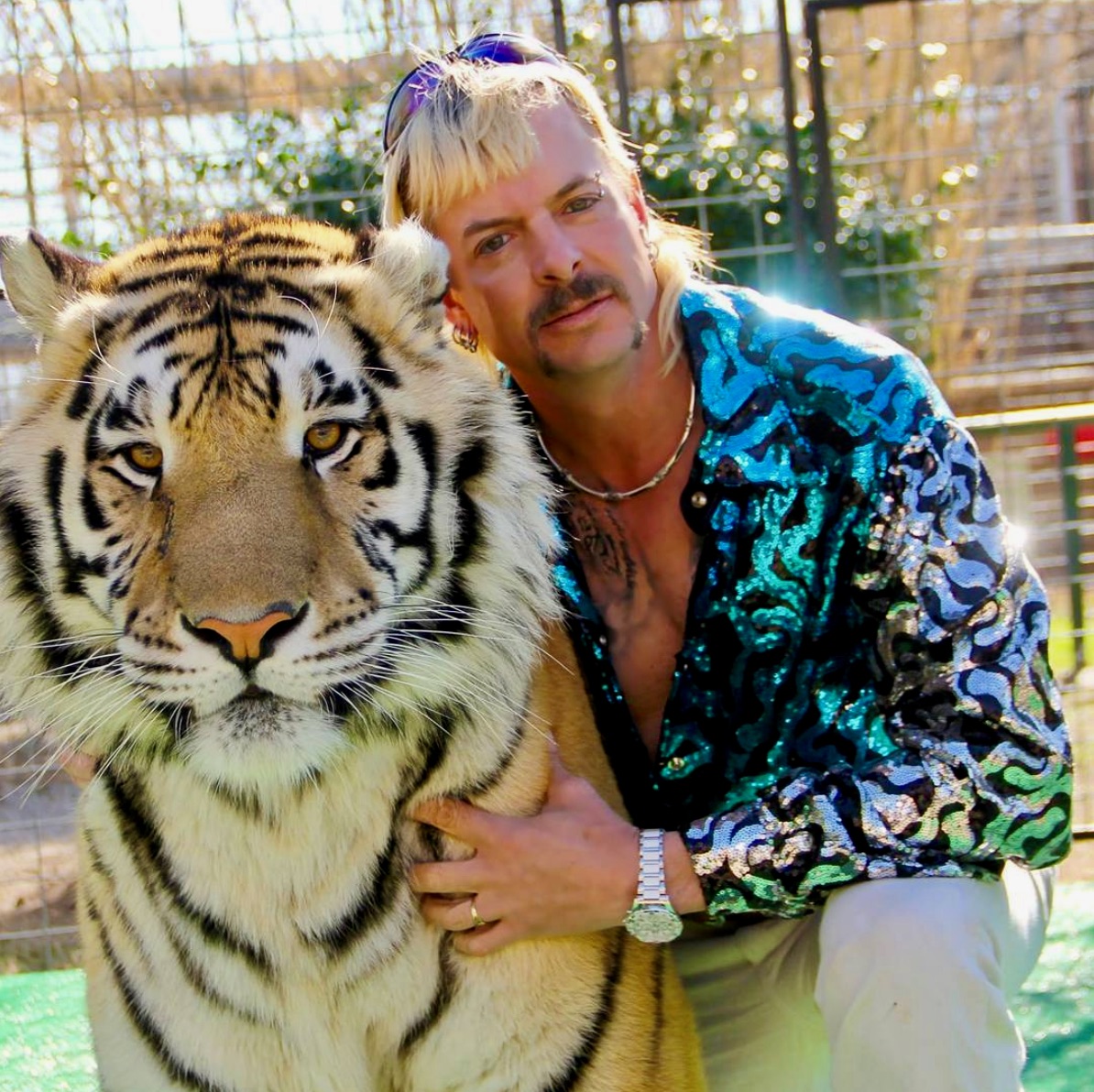

Exotic is wildly paradoxical. He has a bleached two-tone mullet, has a variety of tattoos and wears a Seth Wadley Auto Group baseball cap. He carries around an arsenal of guns and visits the Walmart ammunition counter daily. Joe Exotic’s staff also deliberately play up the “redneck” image. All are dressed in a mixture of flannel shirts, baseball hats, and camouflage shorts, are covered in tattoos and have ponytails.

Yet, Exotic is gay and doesn’t fit the “redneck” image. Gay people are often discriminated

against by people stereotyped as “rednecks.” Exotic is married to two men, wears Western style shirts that are neon and wildly sparkly, and sports a sequined zebra-print cowboy hat.

When I watched Tiger King with my family, we relished the bizarre chaos of the show. The

story of Tiger King is entertaining and fun to watch because you can’t believe it’s true. But my family and I found ourselves cringing at the stereotypes embodied by Joe Exotic’s persona.

After finishing the show and reflecting on it, I realized I wasn’t thinking about how crazy

the story was. I wasn’t thinking about Joe Exotic’s polygamous marriage, the horrifying theory that Carol Baskin fed her husband to the tigers, or even the ghastly animal abuse that happens at private zoos. What was left in my head was the persistent thought that no “redneck” in Oklahoma could be like Joe Exotic. He is a singular being, although the staff do play up a circus version of a stereotypical “redneck.” And then I thought, Wait, why am I thinking of the staff as “rednecks?” Do I believe in that stereotype? Am I reacting as a stereotypical Bay Area liberal white person?

In searching for answers about my own reactions and about the documentary series,

I typed into Twitter, “Tiger King stereotypes.” Up popped a tweet from Shawn Lau, a writer for The New Yorker, The Huffington Post, and many other publications. He wrote, “How

lucky are whites that they can put out something like Tiger King and not have to worry that

we’ll think they’re all like that.”

I’m white, and I realized my reactions were characterized by exactly what I was criticizing

about the show. I hadn’t even considered how other people, not of my demographic, see

the show. As a white person, I didn’t even consider that someone could think Joe Exotic

represented me, my friends, or anybody I know — or that someone could possibly consider him as representative of the average white American!

Lau’s comment shook me up. What if Joe Exotic and the others featured in the show were Asian, or Latinx, or African-American? Some white people would see the harmful stereotypes and jokes as representative of an entire race or ethnicity.

But Joe Exotic isn’t from a minority. He is white. White people can choose to look at

him as an “exotic” aberration of their race. They don’t see themselves represented by him.

White actors, white writers and white directors have dominated film, TV, and other media. They have created myriad representations for white people to choose from. Because white people are exposed to so many different portrayals of white people, they don’t feel that any one story has to be representative of them.

Other groups of people have not had access to the same privilege of complex, multi-dimensional and realistic portrayal. Beyond music and sports figures, these groups are only now beginning to see positive and real versions of people who look like them in the media, media that is directed by people who look like them and enacted by people who look

like them.

As recently as 2016, according to research done at the USC Annenberg School of Communication and Journalism about Hollywood movies, white dominance still held the American film industry in thrall: 70.8 percent of movie characters were white, 13.6 percent were black, 5.7 percent were Asian, and 3.1 percent were Hispanic.

When a stereotype appears in the media of someone who isn’t white, it is easy for white people, trapped in the dream bubble of their own white exceptionalism, to make and rehash those sweeping generalizations that denigrate the other.

It took me a lot of reflection to realize my white privilege while watching Tiger King. I don’t relate to Joe Exotic, rather I find myself in portrayals of white characters like Hermione Granger, the brilliant heroine of the Harry Potter series, or in Rory Gilmore, the studious and kind teenage protagonist of Gilmore Girls.

It was still entertaining to watch Tiger King. But when I think about it now, I don’t cringe at the “redneck” stereotyping, but rather at my ability, as a privileged white teenager, to “other” Joe Exotic and feel like I could never be swept into such a stereotype so distant from my vision of myself.