Infographic created by Tuvya Bergson-Michelson ‘19 using Piktochart. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau, the Wisconsin Elections Commission, and the Office of the Cali- fornia Secretary of State. All statistics calculated using share of two-party vote, except for districts where third-party challengers topped 10% of the vote. For Wisconsin, vote totals refer to the 2012 general election; All California totals refer to the 2012 primary election to control for California’s party-blind “Top-Two” primary system. Due to the absence of a Democratic presidential primary that year, Democratic vote totals presented are much lower than typical California elections.

On October 3, 2017, the Supreme Court heard arguments in Gill v. Whitford, a case that could reshape how we elect congresspeople.

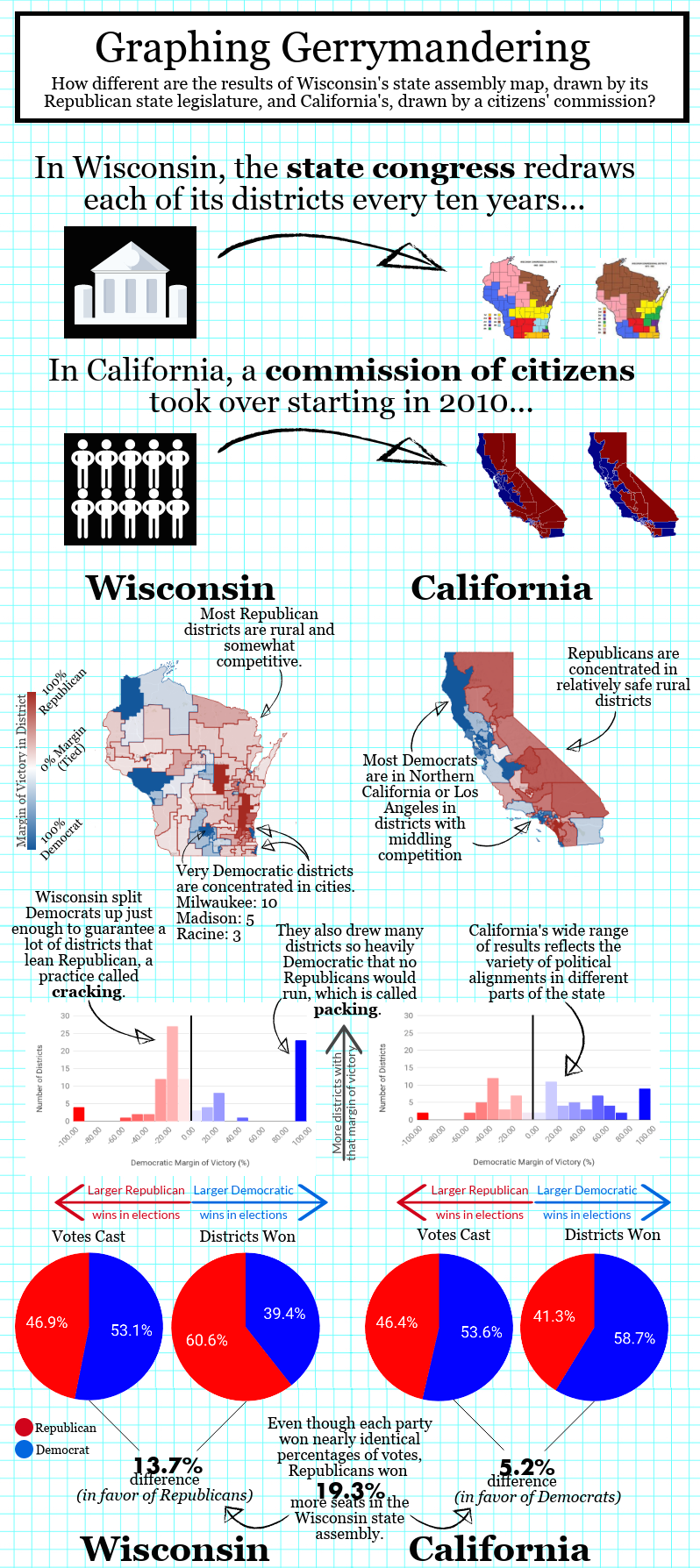

The case challenges the legality of partisan gerrymandering, the practice of drawing the borders of districts for the U.S. House of Representatives and state congresses to maximize a party’s number of seats. Every ten years, after each census, states must redraw the borders of congressional (and often state assembly) districts to account for the movement of population.

Wisconsin’s state assembly redistricting plan is in question. After winning a majority in the state legislature, Wisconsin Republicans drew lines that secured them 60 of the 99 assembly seats in the 2012 election. In contrast, they only received 47 percent of the statewide vote in that election. A group of Wisconsin voters sued.

The case involves a new statistic, a handful of precedents, and countless philosophical questions about American democracy.

A ruling against the state of Wisconsin wouldn’t be the first time that the Supreme Court has altered the process of redistricting. In cases like Baker v. Carr (1962) and Wesberry v. Sanders (1964), the court ruled that all districts in a state must have roughly equivalent populations. The decisions introduced the concept of “one person, one vote” to American law. Opponents of Wisconsin’s map will argue that because Republican votes went disproportionately to winning candidates, and Democratic votes to losing ones, the district lines value one party’s votes over the other.

Recent cases have mostly protected partisan gerrymandering. In Davis v. Bandemer (1984), the Supreme Court suggested that gerrymandering based on party might be non-justiciable—too subjective, complex, and difficult an issue for courts to decide consistently.

Courts have routinely sent redistricting plans that dilute the votes of racial minorities back to the drawing board. Unlike race, though, there is no law against choosing to favor one party. If it rules against Wisconsin, the Supreme Court would likely have to decide how much gerrymandering is too much. Justice Anthony Kennedy worried in 2005 that “no agreed upon substantive principles of fairness in districting” existed at the time. Such principles would need “new methods of analysis” to measure the degree of gerrymandering.

Opponents of partisan gerrymandering think they have found such a statistic. The efficiency gap, developed by political scientist Eric McGhee and lawyer Nicholas Stephanopoulos, allegedly measures deviation from “one person, one vote.” Within each district of a state, the method counts votes for losing candidates and votes exceeding a 50% majority for a winning candidate as “wasted.” The efficiency gap equals the difference between the two parties’ statewide wasted votes, calculated as a percentage of the total votes in the state. In effect, states where both parties win many competitive districts score low efficiency gaps, while states where one party carries many non- competitive districts rack up high efficiency gaps. The developers of the measure suggest that an efficiency gap of eight percent may be a sign of partisan gerrymandering.

Wisconsin’s state assembly districts favored Republicans by an efficiency gap of 15 percent.

In addition to other factors, such as the effects of a landslide election or the history of one party’s dominance in a state, the efficiency gap could be part of a legal test—a definition of partisan gerrymandering for courts to use.

However, the efficiency gap’s critics question the premise of the measure. “In this case, the challengers are asking the court to force state legislatures across the country to fix the Democrats’ political geography problem,” argues National Republican Congressional Committee lawyer Chris Winkelman in an article on SCOTUSblog. Since Democrats tend to live in urban and suburban areas, and more tightly clustered than Republicans, it’s easier to pack them into a few districts. By logical extension, detractors of the efficiency gap argue, a neutral redistricting attempt would likely still favor Republicans disproportionately. Yet, the statistic assumes gerrymandering, rather than geographical distribution of Democrats and Republicans, causes the disparities in wasted votes.

According to research by Jowei Chen, a political scientist at the University of Michigan, the Wisconsin redistricting plan still helps Republicans far more than necessary. Out of 200 party-blind computerized simulations he ran to model a neutral redistricting process in Wisconsin, not a single one exceeded an efficiency gap of seven percent or 47 Republican- leaning districts — both far short of the real-life results. Though the state’s geography does favor Republicans, “drawing a minimally biased map is reasonably possible,” he writes.

More neutral maps still may not guarantee that most voters exert real choice over their representatives. Over 90 percent of incumbent congresspeople still win re-election, partially because most districts have large enough Democratic or Republican majorities that they face no significant threat in the general election. Discussions of redistricting must balance the desires for equal representation of parties and competitive districts.

In fact, gerrymandering in the 19th century favored maps with far more competitive districts, but that maximized the number of seats the party in power could win, says Eric Engstrom, a professor of Political Science at U.C. Davis who specializes in the history of congressional elections. “The more competitive system would better reflect changes in public opinion,” he says. On the other hand, “there are people that argue that safe districts are actually better representative of communities.” The 20th century saw a shift towards the latter system, as reforms ended practices like redistricting whenever a party won a majority and drawing districts with wildly different populations.

Some states have taken redistricting out of the hands of politicians. Starting in 2010, a non-partisan commission (whose members were randomly selected from a group of qualified applicants) has drawn California’s districts. In 2016, California’s elections to the House of Representatives scored only a 0.4 percent efficiency gap, third-lowest in the nation. Similarly, Iowa relies on state employees, who are not allowed to communicate with politicians during the redistricting process. FairVote, an election reform advocacy group, goes even further by suggesting that each district should elect multiple congresspeople, providing more opportunities for a minority party to elect representatives. That plan would require a new law — Congress mandated in 1842 that each district could only elect one representative — but moreover, the focus on party representation might miss a crucial point. “Voters vote based on candidate, not party,” writes Winkelman. Methods that rely on party-based data “make an assumption that is contrary to reality,” he says.

In a lot of ways, today’s political environment looks “a lot like the 1880s and the 1890s,” says Engstrom. “The parties have become so polarized and the system is so competitive at the national level that they’re looking for every advantage they can get.” With the conditions perfect for aggressive gerrymandering, the Supreme Court’s decision could prove a turning point in American history.

Original cartoon by Elkanah Tisdale for the Boston Gazette