On September 24th, the Trump Administration released its third version of the travel ban they maintain is to “detect individuals with terrorist ties and prevent them from entering the United States.” The new executive order added North Korea, Chad, and Venezuela to the list of sanctioned countries, and removed Sudan.

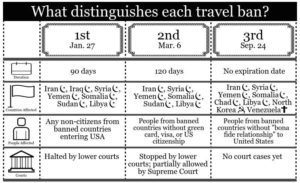

President Donald Trump signed his original executive order on January 27, 2017. It prevented non-American citizens from seven majority-Muslim countries (see chart) from entering the United States. The ban also gave preference to religious minorities from those countries. Since the order almost exclusively restricts the entry of Muslims into the United States, critics quickly labeled it a “Muslim ban.”

In the last ten years, the United States has accepted over 250,000 refugees from those nations. Despite the government’s claim that the ban will prevent terrorists from entering the United States, not a single refugee or immigrant from the seven countries has been responsible for a deadly terrorist attack in the United States, according to the libertarian-leaning Cato Institute.

The travel ban drew nationwide protests as thousands flooded airports to oppose the measure. Federal district courts quickly blocked the executive order.

In response, the Trump administration released a second, similar executive order on March 6th. The new policy clarified that green card holders and other non-citizen permanent residents could still enter the country, and removed Iraq from the list of banned countries.

The Supreme Court released a decision on the second travel ban in the cases Trump v. International Refugee Assistance Project (IRAP) and Trump v. Hawaii. Seeking to balance the interests of both sides, the court’s June 26th decision allowed people with a “bona fide relationship” to the United States, such as relatives of current residents or university students, to enter. However, it upheld

the Administration’s ban blocking others from entering. The Supreme Court also said that they would revisit the cases during their October term, which started on October 2nd.

While the administration may have won that court case, it clearly preferred to release an edited version instead. This choice restarted the legal process challenging the travel ban. The Supreme Court will not hear challenges until federal district and circuit courts have ruled on the most recent version of the policy.

At the center of the legal battles is the question of whether the travel ban discriminates against Muslims on the basis of religion. Critics of the policy say that it violates the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, which guarantees freedom of religion, by primarily targeting Muslims.

The language of the second and third executive orders never mention religion. Instead, they refer to nationality. The administration’s lawyers argue that this difference excludesthemfromtheEstablishment Clause. Parts of the Establishment Clause argument are unprecedented: freedom of religion has never been used before to overrule immigration policy.

Many constitutional lawyers disagree with the administration. “The only way to rule for the government on the Establishment Clause is to ignore the evidence,” says David Cole, legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union. Cole helped file the Trump v. IRAP lawsuit. “Muslims in America are the target of the mission.”

The addition of Venezuela and North Korea in the third executive order, neither of which are Muslim, may have been an attempt to avoid the charge of religious bias. However, the ban only limits Venezuelan government officials, and few North Koreans immigrate to the United States, so the vast majority of people affected by the ban are still Muslim.

Critics of the ban often cite Donald Trump’s rhetoric — during his campaign, he called for a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States” — as evidence that the ban is founded in anti-Muslim prejudice. District and circuit court judges have argued that this prejudice, called animus in constitutional law, could make the executive order unconstitutional. Josh Blackman, a professor at the South Texas College of Law and adjunct scholar at the Cato Institute, says the Supreme Court must decide whether Trump’s statements about Muslim immigrants and refugees on the campaign trail are relevant to the case. How courts deal with animus in this case could set precedent on using President Trump’s quotes as evidence. As Blackman muses, “How do we treat such a norm-busting president?”

In June, the Supreme Court did not rule on either the Establishment Clause or animus. Instead, its “bona fide relationship” compromise led to legal grey areas. Justice Clarence Thomas worried that the court’s decision would “invite a flood of litigation.” Professor Blackman is also concerned. “I don’t know what that does to the law,” he says. Continued lawsuits prevent him from explaining to his students “what the heck the law is.” Without further guidance, courts could issue contradictory rulings on the new ban, which would create a headache both for immigration administrators and for advocates for refugees. In the past, federal courts have mostly ruled against the government. That may hold true for this executive order, too.

If cases on the ban reach the Supreme Court again, a ruling in favor of the ban may be the most likely scenario. Justice Thomas’ June opinion notes that “the Government… is likely to succeed on the merits,” and Professor Blackman points out that Justice Kennedy — the court’s typical swing vote — probably wouldn’t have voted to hear Trump v. IRAP and Trump v. Hawaii if he didn’t find the circuit courts’ decisions “objectionable.”

On the evening of October 9th, protesters gathered for a “No Muslim Ban Ever” candlelight vigil at Civic Center Plaza. Demonstrators gave varied reasons for attending.

I’m here to use my body to show solidarity. —Jack Leng, UX Designer

The Muslim Ban is something that seems distant. We hear about policies like it, but we don’t understand the impact until events like this. —Saamia Haqaq, Political Science major at UC Berkeley

This policy targets groups on religious and national identity, not guilt. That is wrong. —Hatem Bazian, Co-founder of Zaytuna College

It’s important to speak up against discriminatory policies, and for people who have their identities criminalized. —Jehan Hakim, Asian Law Caucus

I want a diverse nation because we all learn from each other. —John Hayashi, Japanese American Citizens League

My parents are both immigrants… I can only imagine what it’s like to get [the opportunity to immigrate] taken away. —Saamia Haqaq, Political Science major at UC Berkeley