In early June, Aidan Kohn-Murphy posted a TikTok responding to a video by a young woman who claimed that she, as a California Republican, was being “enslaved” by the Democratic Party.

In his response, Kohn-Murphy takes the creator to task for equating life in a Democratic state to slavery. “You’re not enslaved to the Democratic Party just cause gay people can get married now,” he says. He also pushes back on her assertion that “Trump cares” by displaying an image of Melania Trump in a jacket emblazoned with the words “I really don’t care, do u?” which the First Lady wore on her way to visit a migrant detention facility at the southern border.

Kohn-Murphy’s video, which he now says he regrets making, quickly went viral. He invited the creator of the original video to be the first guest on his newly-launched podcast, which he said was an opportunity to “talk about the video, talk about racism, talk about Trump and have some great civil discourse, because that’s how you change minds.” She agreed, and the episode was posted online a few days later.

(That creator left TikTok after receiving threats from Kohn-Murphy’s fans, though he repeatedly implored them to leave her alone. For privacy reasons, her name is not used in this story.)

Kohn-Murphy, who is 16, is more commonly known by his TikTok username, “politicaljew.” On the app, where he has over 135,000 followers, he posts videos discussing politics and cultural issues and frequently uses his platform to carefully dismantle conservative arguments. Progressives, he says, have been right “in 95% of history,” and his videos often dissect in minute detail all the ways in which he believes conservatives are wrong and progressives right.

Not all of his videos deal with politics, though. In one, posted on May 22, Kohn-Murphy appears with his head partly wrapped in a blanket. “Am I the only one who literally can’t do a pull-up?” he asks, then adds, with a slightly embarrassed smile, “I hope not.”

In his next video, posted the same day, he rails against the Electoral College while wrapped in the same blanket.

For Kohn-Murphy, who lives in Washington, D.C., and whose parents met while working in U.S. Senate offices, politics have been ingrained in everyday life since the very beginning.

When he was two or three years old, his family attended a charity event where then-President George W. Bush appeared as a guest. “Whenever we would see George Bush on TV, my dad would point at him and say, ‘That’s a bad man. That’s a very, very bad man,’” Kohn-Murphy said. At one point during the event, the family had an opportunity to take a photo with Bush. “My parents were both very nervous that I was going to look at George Bush and say, ‘There’s the bad man!’” he recalled. “Luckily, I was able to read the room and I didn’t say it.”

At seven years old, Kohn-Murphy testified in front of the D.C. Council with a simple request: bring chocolate milk back to Washington’s public schools. “I interviewed everyone in my school, including the teachers—which I think was a total of 600 people—about their previous drinking habits, what they were doing now, and a few other questions,” he told me with a smile, reflecting on the challenges he faced trying to collect survey responses from so many people at such a young age. “Then, I put it into testimony and went in front of the D.C. Council and lobbied them to get chocolate milk back in D.C. public schools.” The measure ultimately failed after the chairman of the council, who Kohn-Murphy described as his “biggest advocate,” was charged with bank fraud and forced to give up his seat.

Last year, Kohn-Murphy spent the summer as an intern for D.C. Council Member Robert White, where he conducted research on animal cruelty legislation. And in January, he testified to the Council again—this time to support proposed anti-vaping laws after a smoke shop opened near his school.

“He’s a go getter,” said Ari Kohn, age 17, Kohn-Murphy’s cousin and podcast producer. “He sees an opening. He sees a change that he wants to fulfill and he goes and he does it.”

In March, as the U.S. began to shut down due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Kohn-Murphy was gearing up for his next project: a polling firm that would work with D.C. Council candidates ahead of the 2020 election. He recruited Kohn and some friends, and together they founded Next Generation Polling.

But developing a sampling formula that took into account the demographics of a city of 700,000—and then executing it—turned out to be “a lot more complicated than I realized it was,” Kohn-Murphy said. “I basically failed.”

The polling team eventually lost contact with the first candidate they planned to work for, and they never conducted a poll.

But while Washington offers ample opportunities for young people interested in politics, it lacks the ideological diversity that would make the city more reflective of the national political landscape. Hillary Clinton won the district by 86.8 percentage points in 2016, one of her largest margins of victory anywhere in the country. (By contrast, Clinton won San Francisco, widely considered to be the most liberal American city, by 75.3 percentage points.) And, Kohn-Murphy noted, in the 1984 presidential election, when Republican Ronald Reagan won every state except Minnesota, Washington voted for Democrat Walter Mondale by a margin of more than six to one.

Kohn-Murphy’s high school falls largely along the same lines. Earlier this year, before the pandemic, a poll Kohn-Murphy conducted of his classmates showed that only 3% identified as Republicans. He described this finding as “a pretty huge relief.”

But being in such an ideologically homogeneous place, he pointed out, means political discussion is limited. “I’m kind of in an echo chamber,” he said, “in the sense that there are three or four Republicans in the entire school, and we all know who they are. There’s not really much room for debate.”

Instead, much of the debate happens on TikTok. This spring, when schools closed, the amount of time teenagers spent on the app surged. Kohn-Murphy’s account wasn’t left behind. Scrolling through his videos, political commentary is interspersed with shock and bemusement as he accumulates more and more followers. “I’m very confused as to how I ended up in this position of having any followers, cause all my content is so weird and random,” he says in a video upon reaching 2,000 followers in mid-May. A few days later he posted a video thanking his followers when he hit 6,000, and again the next day at 11,000.

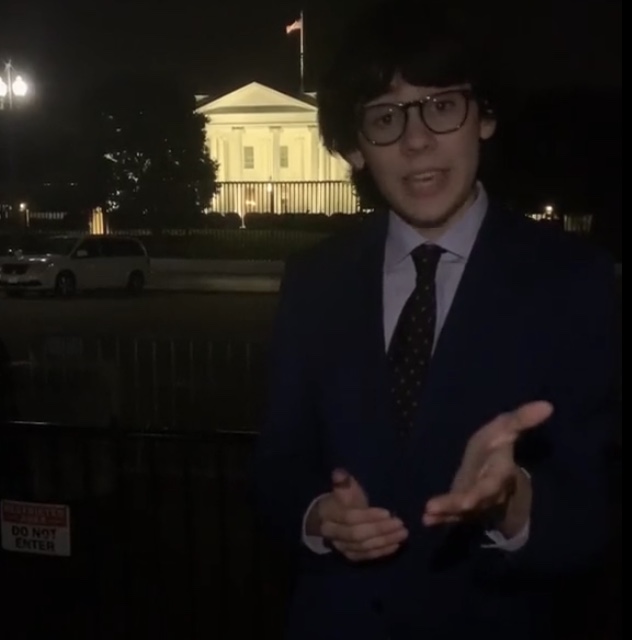

Now, as he nears 140,000 followers, Kohn-Murphy credits his popularity to his ability to combine humor and politics. Many of his most popular videos, including renditions of Cardi B’s “WAP” outside the U.S. Capitol building and the White House, are meant to be more funny than they are political.

“Aidan knows what he’s talking about, but he’s also absolutely hilarious,” Kohn said. “He is a decent and kind and warm person, and that comes through in his videos. That’s something you can’t fabricate.”

Sydni Gift, who directs Kohn-Murphy’s Next Generation Politics Podcast, added that his videos are even more powerful because he’s only 16.

“I’m a teen, and I like politics,” Gift said, “but everyone in politics is really old and not funny. Aidan is hilarious, and he talks about issues that are important. I feel like that’s so refreshing to see.”

“He’s a little bit awkward and quirky,” she added, “so I think that makes it even better.”

Kohn, who described Kohn-Murphy as her “sibling, best friend and cousin all in one,” recalled a specific moment that she said exemplified Kohn-Murphy’s ability to draw people in: After an argument they had about the merits of single-sex schools, she invited Kohn-Murphy to spend a day with her at her all-girls school. He agreed, “and by the end, he was more popular than me,” Kohn said.

Kohn-Murphy’s videos often come across as spontaneous, spur-of-the-moment trains of thought on complex issues, ranging from voting rights to police violence to ways to get involved in various campaigns.

But many of his videos have a singular, unwavering focus: debunking conspiracy theories.

Kohn-Murphy first experienced the consequences of a conspiracy theory in December of 2016, when a man with a gun entered Comet Ping Pong, a pizzeria in Washington, and fired three shots into a closet. (No one was injured in the shooting.)

Kohn-Murphy, then age 12, was across the street watching the New England Patriots at a sports bar with his family. “It was really, really scary,” he said, recalling his confusion as the bar went into lockdown without explanation.

In the long-ago debunked conspiracy theory that inspired the shooting—dubbed “Pizzagate”—Comet Ping Pong’s basement played host to a Satanic cult and a child sex abuse ring that involved prominent Democrats, including Hillary Clinton. Recently, the conspiracy has seen a resurgence among members of QAnon, a far-right group that claims President Trump is fighting a “deep state” of Satan-worshippers, pedophiles and child-eaters.

Comet, Kohn-Murphy said, is “somewhere that I’ve gone for my entire life. I’ve been to bar mitzvahs there. I’ve been to parties there. I love Comet pizza. That made me realize that I need to do everything in my power to make sure that people aren’t falling for these conspiracy theories.”

He worries, though, that young liberals are increasingly susceptible to conspiracy theories as well. “We often neglect to do our basic research and just see things and automatically trust them,” he said. “It’s scary to me because it empowers more people to do crazy things, like what happened at Comet.”

To a lesser extent, Kohn-Murphy’s worries came true on the night of May 31. That night, as protesters filled the streets of cities across the country to protest police brutality in the wake of the killing of George Floyd, rumors of an internet blackout near the White House began spreading on social media. The police, people alleged, were taking advantage of the blackout to kidnap and murder protesters.

There was no evidence to support that claim, and the theory was quickly debunked. Protesters had, in fact, been posting on social media from the area in which the blackout was purportedly happening. But the conspiracy, which came to be known as the D.C. blackout, quickly gained traction among young liberals online.

Kohn-Murphy took to TikTok to assure his followers that no such blackout was taking place. Within minutes, though, comments began pouring in under his videos accusing him of being a government plant, a situation he described as “not great.”

“I wish I were a government plant,” he joked in our first interview. “I wish they were paying me, and I could afford proper lighting for my podcast. But no, they’re not.”

So, Kohn-Murphy did what any teenager would do: he filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the District of Columbia to obtain security camera footage from the night of the protest.

When the footage arrived on a flash drive a few days later, he live-streamed it for all of his followers to see.

As he had said, there was no unusual activity.

“My goal was to get as many people as possible to see my video, and realize that what they were saying was fake and dangerous,” he told me. “It’s very scary to see people believe these conspiracy theories, especially ones that have been debunked.”

Kohn-Murphy identifies as a democratic socialist, but said the label can be confusing. Republicans, he noted, frequently weaponize such labels against Democrats, calling even the party’s most moderate members—including Joe Biden—socialists, communists, Marxists and anything else to fire up their base.

“I would say I’m most aligned with Elizabeth Warren or Bernie [Sanders],” Kohn-Murphy said. “I haven’t fully made up my mind about capitalism, but the problem is it doesn’t really matter because we’re not going to be a communist—or even a socialist—state anytime soon.”

In the Democratic presidential primary, though, Kohn-Murphy worked for Pete Buttigieg. He stressed to me that he joined the campaign early on, before Buttigieg “made his centrist pivot.”

Over the course of about 15 campaign events that he worked at, Kohn-Murphy said he met Buttigieg around 10 times. “It was a great political experience and one of my first political jobs,” he added.

I first spoke with Kohn-Murphy on Zoom in late July. When he joined the call, his background was a photo of Senator Ed Markey, Democrat of Massachusetts. “Sorry I’m late,” he said, clicking the background away. “I was just finishing up a phone bank for Senator Markey.”

Markey has recently become something of a star among young progressives for his co-authorship of the Green New Deal with Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Democrat of New York, and his support for a slew of other liberal policies. Kohn-Murphy was a fellow on Markey’s Senate re-election campaign, and, among other things, helped to run Markey’s TikTok account.

In July, the campaign began posting a phone banking leaderboard to encourage volunteers to call more voters. Much to Markey’s advantage, the competition between Kohn and Kohn-Murphy was intense. For the rest of the campaign, Kohn said, she and Kohn-Murphy vied for the top spot, alternating between first and second place for weeks.

“We use each other to motivate ourselves and to motivate each other,” Kohn said. “I’m like, ‘Well, Aidan’s doing this, so I better get a leg up.’”

Kohn-Murphy echoed that sentiment. In one of our interviews, he described Kohn as “my cousin who’s a little bit better than me at everything.”

Ultimately, Kohn finished first in calls made, with Kohn-Murphy coming in second. Their positions were reversed for supporter pages, a way for volunteers to engage their social circles in the campaign.

Markey handily defeated his opponent, Representative Joe Kennedy III, in the Democratic primary earlier this month, effectively guaranteeing his return to the Senate.

Heading into the fall, though, not much else was guaranteed, least of all the future of TikTok itself. The Trump Administration announced last month that the app, which is owned by the Chinese company ByteDance, would be banned in the United States on September 20 unless an American company purchases it.

The Trump Administration reaffirmed that statement on September 18, announcing that both TikTok and WeChat, the Chinese-owned social media platform, will be banned from U.S. app stores on Sunday. After midnight on Sunday, WeChat will not be supported on U.S. web servers while TikTok has until November 12 to take actions to ease the Administration’s concerns about national security.

Throughout the confusion over the fate of his platform, Kohn-Murphy maintained a sense of calm while also lending his voice to a call to action. “This is not an ideal situation to be in,” he said in a TikTok shortly after Trump announced plans to ban the app. Quickly, though, he turned his attention toward the future. If TikTok disappears, he told his followers, “The best thing that we can do to get back at [Trump] is organize for Biden. If you’re of voting age, make sure that this is your call to vote.”