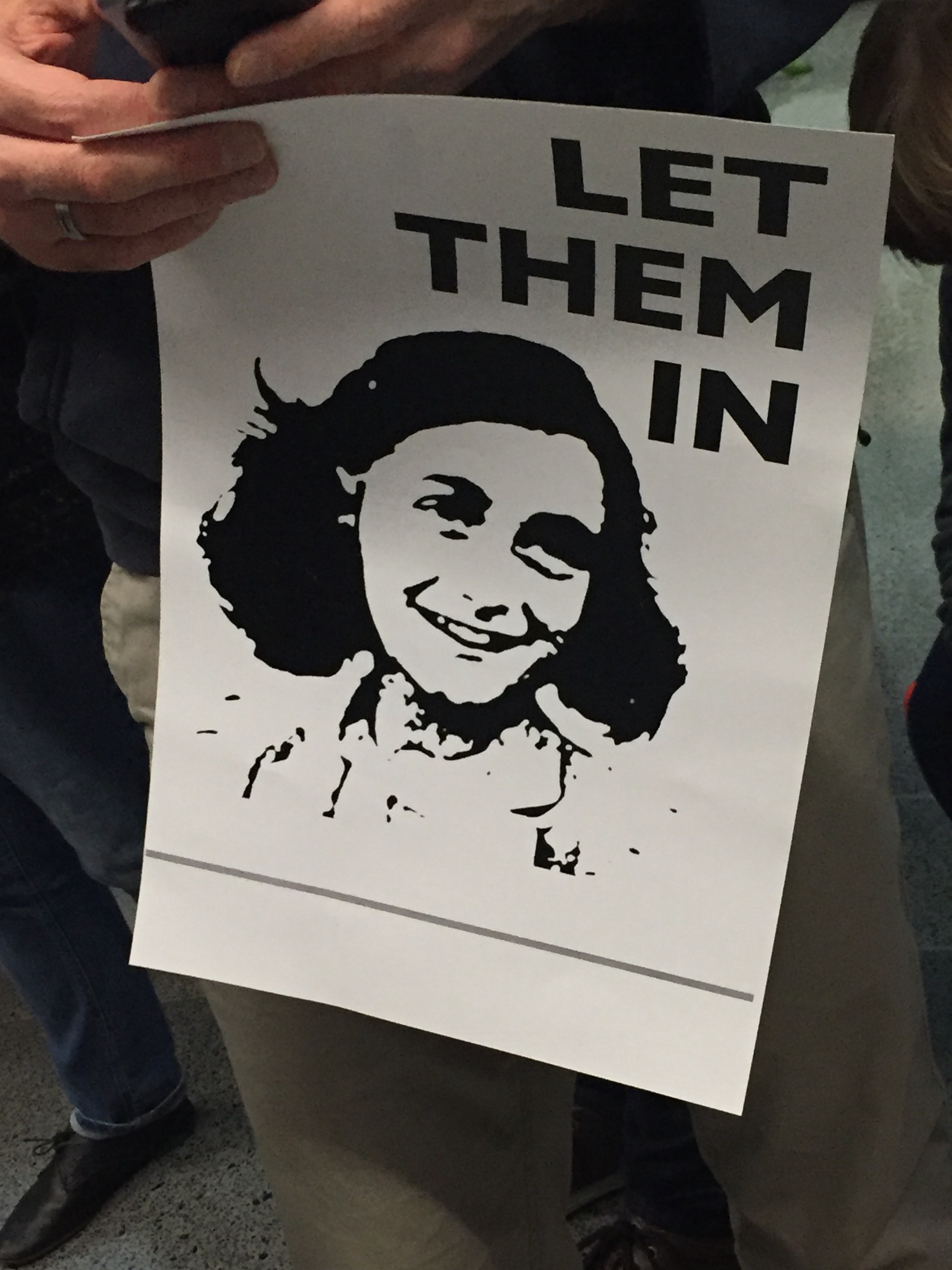

Following President Trump’s executive order banning immigrants from seven majority Muslim countries, the United States burst into protest. Crowds gathered at airports in major cities all over the US, condemning Mr. Trump’s actions. Members of the Lick community share their experiences protesting at SFO

—Raayan Mohtashemi ‘17

photo by Leila Shokat

Lydia Greer

I attended the SFO protest because I believed that if there was any chance that the detained immigrants and refugees could hear us or see us then it would be worth my participation. I left impulsively after interviewing prospective students on Saturday at LWHS. I made a sign and got on the Bart.

The sign said: “The American People Welcome Refugees” and “Immigrants, Love Not Hate.” I have close friends from Iran and Yemen, I went on their behalf. I believe in the power of images. If the image of thousands of people at airports around America protesting a ban barring entry of people from seven countries of predominantly Muslim faith could reach a child or family watching television who are suddenly persecuted because of this ban then the picture is important.

When I got to the airport I met my partner Jeff who had a small hand-written sign and had gotten there earlier. There were hundreds if not thousands of multigenerational people from many faiths (Muslim, Jewish, Christian, Buddhist) chanting and holding signs. It was very peaceful and very moving.

photo by Carrie Maslow

We stomped on the ground so that the floors shook and yelled, “Let the Lawyers In, Let the People out.” Gavin Newsom came to shake people’s hands in the audience. In fact, there was a stay granted on the ban and the people in airports were released. I believe it was because of the “chaos at the airports” caused by people with the impulse to stand up. I am motivated to stand up in the coming months. I believe in images and their power to heal or to hurt.

Here is a Rebecca Solnit quote from Hope in the Dark, a book about cultivating the hope that can inspire action. “This means, of course, that the most foundational change of all, the one from which all else issues, is hardest to track. It means that politics arises out of the spread of ideas and the shaping of imaginations. It means that symbolic and cultural acts have real political power. And it means that the changes that count take place not merely onstage as action but in the minds of those who are again and again pictured only as audience or bystanders. The revolution that counts is the one that takes place in the imagination; many kinds of change issue forth thereafter, some gradual and subtle, some dramatic and conflict-ridden—which is to say that revolution doesn’t necessarily look like revolution”

Anton Krukowski

I went to SFO with my close friend, his two preschool aged daughters, and his niece. We have known each other since 2000, and we had gone to antiwar protests together in 2003. He is Palestinian, grew up in Kuwait, and his family escaped during the first Gulf War. On the drive home, he was reminiscing about arriving at SFO with his family as war refugees when he was 12. His parents heaved a sigh of relief as they were finally in a country where they could be themselves, and call it home. In Kuwait, they had been treated as third class citizens for his entire childhood. The US had immediately felt welcoming.

My own father had arrived with his family as WWII refugees at about the same age, about 50 years earlier, and eventually called this strange country home as well. It was very healing to be at SFO, to see so many like-minded people, chanting, shouting, teams of lawyers and translators at the ready, apples, tangerines, cookies and granola bars being distributed for free on empty luggage carts, and all the signs: “Jews for Muslims,” “Nothing About This is Normal,” “Sanctuary for All.”

This is the country we have been, and we need to continue to be. My friend’s niece is 11—about the age my friend and my father were ultimately welcomed as refugees. She knows her family’s history well, and I think she will never forget yesterday.

Linnea Ogden

I am working to get over my personal anxieties about protest and direct action (fear of conflict, aversion to chaos and crowds), and show up in the ways that I can. Especially as a white person who has been and is historically and institutionally privileged in so many ways, I need to show up. I’m grateful I was able to go to SFO on Sunday, grateful to the organizers, the brass bands, people who brought food, those who held it down overnight, and those who came back—to everyone for their care, anger, and purpose in resisting the Islamophobic order banning travel from predominantly Muslim countries.

I second-guess my actions, especially with relation to protests and social justice: Am I doing enough? Am I doing all I can? Am I taking up too much space if I go? Am I still in solidarity if I don’t? If I can go, I want to be there with an attitude of receptiveness and respect for the larger goals. If I can’t go, I will show up for the phone call, the lunch talk, the donation, the conversation, the lesson. There is always another opportunity to show up.

Carrie Maslow

The SFO protest this past weekend was very moving— inspiring and heartbreaking at the same time. I went to meet up with members of Indivisible SF and was surprised by the giant turnout and volume of the crowd. I encountered Raayan Mohtashemi ‘17 and Kelby Kramer ‘17 in the downstairs level of the international terminal. The experience was inspiring because of the simplicity of the messages which are so obviously true and cut to the common ground we all share—“everyone is an immigrant,” “you are welcome here,” “yes you can!”… in response to a Muslim woman saying she just wants a place where she can feel safe to pray. Since half of my family is Jewish, the haunting messages- “never again…” “and then they came for me” were very powerful. It was also heartbreaking because, clearly, there were people there for whom the ban is imminently terrifying or brings up a lot of emotion.. For example, two men near me were chanting loudly with the crowds but also crying throughout the protest. I wish I could know their stories.

Ernie Chen

I need to check my privilege of all of my blood relatives being American citizens. This past Saturday, my parents flew into SFO from Hong Kong at 9 p.m. just as the protesters were gathering strength in reaction to the executive orders signed earlier that day. Arriving passengers in the international terminal at SFO were diverted to a different exit and there was no indication to those of us waiting where to go. After 45 minutes of searching, asking people around us and trying to hear each other on the phone over the loud protesters, I located my parents. Annoyed, yes. But ultimately thankful that I didn’t have to worry about whether or not I would see my parents again.

Cat Fung

We need to think about this executive order in the context of a longer history of immigration bans. The first race-based immigration ban that the US instituted was the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. Later, the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act would establish a “national origins” quota system, which favored western European immigrants. In the 1960s, as the US faced both foreign and domestic scrutiny over its discriminatory immigration system, and as the US tried to make allies with more nations, and as the US wanted to invite more immigrants to help build its industrial infrastructure, the 1965 Immigration Act (also known as the Hart-Celler Act) was passed, which declared that no person could be “discriminated against in the issuance of an immigrant visa because of the person’s race, sex, nationality, place of birth or place of residence.” Instead, our immigration system would give priority to relatives of US citizens and professionals with specialized skills. Our current immigration system is still based on the 1965 Immigration Act.

So, this executive order banning the entry of immigrants from particular countries is hearkening back to the discriminatory system the US used to have before 1965. We are already seeing lawyers and policy makers argue that this ban is unconstitutional. We will see if such an argument will hold, and what kind of process will be required to overturn the order. The process will require public pressure, which is why I was at the protest.

Raayan Mohtashemi

photo by Carrie Maslow

After Trump signed the executive order banning travel from 7 Muslim-majority countries, I heard of the protests at SFO. On Saturday (the second day of protests), I went to SFO with my friend Kelby Kramer. My main reason for going to SFO was to see if I could help out in any way as a Farsi speaker. I’m Iranian-American, so Trump’s executive order has had an especially personal impact on me. Any of the people being detained by immigration authorities over this ill-advised and ill-planned travel ban could have been my grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, or friends. I imagined my life without my grandma, who helped raise me when I was young, or my cousin, who came here to study under a student VISA and I have grown close to since she moved to San Francisco. I was deeply saddened, so I tried to help out in any way I could by offering to translate and/or advocate for detainees. Luckily, there were plenty of experienced Farsi-speaking lawyers helping out, so Kelby and I joined the protest. There were two large groups in the upper departures section (at each security checkpoint) and two large groups at each exit in the lower arrivals section of the main International Terminal. When I was there, the security checkpoints and arrivals lobby were all open. We saw Leila Shokat ‘17, Ms. Maslow, and through social media heard about many other friends joining the protest. It was uplifting to see and hear so much support from the Lick and Bay Area community, and I’m glad that legal challenges to Trump’s travel ban have resulted in its temporary stay. This ban has given me a greater perspective for the impact of immigration laws that I am still struggling to comprehend. I have heard heart-wrenching immigration stories from all over the globe and throughout history, but never understood how easily lives could be disrupted by politics until I experienced this fear and uncertainty myself.

Leila Shokat

My mom and I approached a crowd on their feet, all facing in toward a circle of people seated around piles of signs from the previous evening’s protest. They were chanting, “Let the lawyers in,” as those being detained at the airport were not being allowed to have lawyers. A small group of immigration lawyers, offering free counsel, was gathered next to the airport Starbucks, working on their computers and talking to reporters. We were led in various chants by a small group of women. Every so often, someone would call for a “mic check” and make a speech, updating us on new information and rallying us all around one central message: unity. The leaders emphasized the importance of operating as one, harnessing the power of the hundreds of people gathered at SFO to contact elected officials via twitter and phone calls, pushing them to use their power to release the people being detained. When we first arrived, there was an elderly Iranian couple who were in the process of being deported. Two and a half hours later, the couple was released. The crowd erupted at the news. It made us feel that the protest and pressure on people in power actually had a direct impact.