This April, Lick-Wilmerding’s South Asian and Middle Eastern community (SAME) celebrated their heritage month. They share their often unheard experiences within the LWHS community.

Students and FacStaff offered gratitude for being a part of a racially diverse community, both within the SAME affinity space and the whole school. Lori Agbabian ’24, said, “Going to Lick where there are a lot of students of color, I feel like people understand me a little bit more, and I try to see myself in other people.”

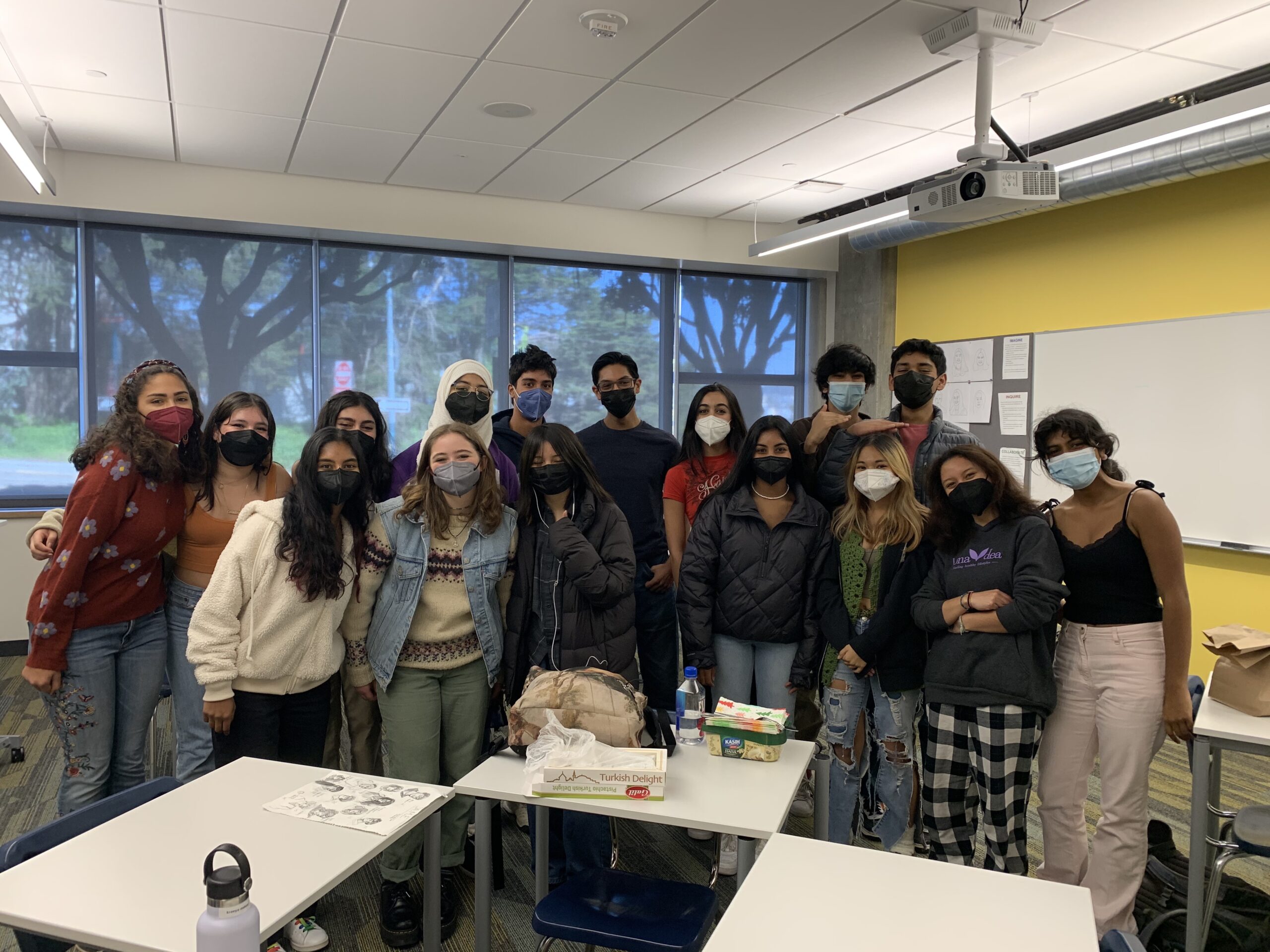

Annual SAME chai meeting. photo courtesy of Miranda Rodriguez

Students also shared how this doesn’t always translate to representation with individual identities. Interviewees relayed how they are often one of just a few or the only student of South Asian or SWANA descent in a class. “I’m Armenian-American, so there isn’t much representation,” Agbabian ’24 said.

Agbabian elaborated on her specific classroom experiences. “I remember for Modern World History we were reading about World War I,” she said. “One crucial part of WWI was the Armenian Genocide, and there was one little section in the textbook that talked about it. I was just so happy to see it represented that I took a picture of it.”

One might wonder how many students at LWHS identify as South Asian or Middle Eastern. This is a more complicated question than it seems, as explained by Director of Admissions Davion Fleming.

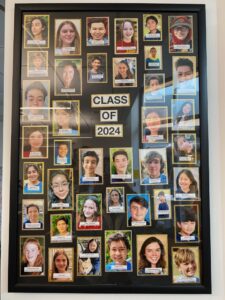

“Folks may not always identify in ways the survey provides. There is a box for Middle Eastern Students, there isn’t a specific South Asian option,” he said, referencing ethnicity choices on the LWHS application. Discussion of this issue isn’t new either — the “Middle Eastern” choice was first introduced on applications for the class of 2024 after efforts were undertaken by the SAME club in the previous year.

The question can still be complicated, though. The term “South Asian” remains unspecified within Asian options and the term ‘Middle Eastern’ itself can be ambiguous. It generally references SWANA, South West Asia and Northern Africa, a modern, geographical term that doesn’t contain the same colonial roots as “Middle Eastern.” Davion explained, saying, “Students may choose not to disclose, or choose ‘other’ with varying descriptions. Right now it shows we have 13 students who identify as Middle Eastern, and 30 students who say they identify as South Asian.”

Not included in these numbers are students who may have chosen the “other” box and written anything other than “South Asian” or “Middle Eastern,” such as their specific ethnicity, the country their families may have immigrated from or a more geographically accurate term.

Misperceptions of religon are also a common theme within SAME identity. Zainab Ansary ’25 said, “I’m South Asian and also Muslim, and I feel like Islam is treated like a race. People are really surprised that I’m South Asian. Their first guess is always that I’m Arab.”

Director of Technology and SAME advisor Adnan Iftekhar said, “Right now it is Ramadan and I know there are FacStaff and students who are observing in different ways, including fasting. For me, it is part of who I am… FacStaff events like breakfasts can be challenging.”

Media portrayals of these demographics seem to have common underlying stereotypes. Portrayals of the “Middle East” tend to imply Muslim undercurrents, and South Asian identities are often perceived as synonymous with Hinduism. Yet over 15 religions are practiced across South Asia and SWANA, not to mention various religious sects.

Students/FacStaff shared their positive experiences alongside experienced religious assumptions.

Tech Arts teacher and SAME advisor David Sasson shared his different experiences at LWHS. “I’ve only been at Lick for two years, so I don’t feel like [my identity] has stood out, but it’s great to see a diverse SAME community on campus,” he said. “My cultural identity is many things. I see myself as Persian-Kurdish-Jewish. Kurdish people are often forgotten about, mostly because we don’t have our own autonomous country. When it comes to Jewish identity as well, it can sometimes be generalized about people who are from Europe, even though it’s very tied to the Middle East. That (misconception) exists not just at LWHS, though, but western society as a whole.”

Another shared experience of members of the South Asian and SWANA community seems to be that of being an involuntary ambassador — of being regarded as a representative for an entire race, religion or geographic region.

“I was used to having to be a South Asian representative in my middle school. It was kind of heartbreaking to come into Lick and feel like I’m in the same position again. I’m totally fine with questions, but that responsibility is really heavy,” Ansary said. “It’s really insensitive if you think about it, a lot of these questions are invasive, rude. A lot of them come off as ‘why are you so backwards’… A few minutes ago I got asked if I can wear ear buds.”

These encounters with culture may be informed by lack of visibility, Yet, this ignorance can still be rooted in colonial narratives. Characteristic of ‘western’ societies such as ours, they can be tiring to navigate daily.

Sasson said, “Most people think of the idea of where someone is from, and they don’t consider all the changes a region may have gone through in the past hundred years… I get the occasional lumping in with other Middle Eastern cultures… things like ‘oh you’re Persian (or Kurdish,) I just had hummus last night’ but that’s also a greater western society thing, not just at Lick. I think I want people to understand that being Kurdish is its own ethnicity with its own history, traditions and cultures.”

Iftekhar said, “There’s always room for improvement with the way we address narratives about global political events. Now, there is a conflict that’s happening in Ukraine. At the same time conflicts are taking place in Yemen, Somalia, Palestine, Ethiopia and more.”

Agbabian said, “[When it happened,] there wasn’t that much coverage on the war with Artsakh. It was a really hard time for my parents and the Armenian community. I was just entering high school and my parents didn’t want to worry me about it, but people still don’t know what happened. I wouldn’t say I feel bad about talking about it, but I don’t want to sound selfish.”

Upon reflection, some interviewees found themselves asking what it means to be South Asian or SWANA in a school that holds diversity in high regard. Expressing the complicated aspects of SAME identity in an environment where all non-white students can be grouped into one ambiguous entity, they hoped for an environment where all BIPOC students can feel heard and understood.