As 2024 came to a close, the doors of a four decades-old institution came to a close as well: the San Francisco Contemporary Jewish Museum (CJM). For Bay Area Jews, the museum’s final exhibition—California Jewish Open—was a moment of controversy, a celebration of community and a poignant goodbye all at once.

Founded in 1984, the California Jewish Museum was originally stationed at a small gallery near the city’s waterfront. In 2008, however, Polish-American architect Daniel Libeskind was hired to construct a new building downtown. Made mostly of red bricks, the building’s design is based on the two Hebrew letters spelling “L’Chaim,” meaning “To Life.” Together, the museum’s education center, exhibition gallery and auditorium—among other spaces, such as a cafeteria—helped to attract 20,000 visitors annually.

However, these 20,000 visitors were not enough. In November 2024, leaders of the CJM announced the museum’s closure due to lower attendance following the COVID-19 pandemic. This comes as many galleries, libraries, archives, and museums (GLAMs) shut down nationwide in 2025, including the Rubin Museum of Art in New York City, the Faith and Liberty Discovery Center in Philadelphia, and the California Historical Society in San Francisco.

For its final exhibit, California Jewish Open, the CJM invited Jewish artists in California to submit artwork inspired by a simple theme: connection. Almost five hundred pieces ended up being submitted. On opening night, visitors had to wait an hour in line to see the forty-seven artists with featured work.

To curate the exhibit, the CJM chose Elissa Strauss, Artistic Director of LABA BAY AREA, a laboratory for Jewish culture. By the end of the curatorial process, Strauss had organized the selected artworks into four sub-categories: connection with the Earth, connection with other humans, connection with the past/future and connection with the Divine. Ultimately, Strauss sought to highlight the wide range of dreams and concerns of Jewish artists at the time. This felt especially relevant amidst the Israel-Hamas war, which was killing hundreds of people by the day—and spurring Jews worldwide to contend with feelings around identity, loss, community and confusion, among others.

In fact, many artists found the California Jewish Open an opportunity to process their heartbreak. One of these was Kim Kyne Cohen, a sculptor based in Los Angeles who featured a grape juice bottle with the words “oy vey!” on the front. As many Jews know, “oy vey,” meaning **“oh wow” in Yiddish, is a quick way to express shock. “There are no words for what happened and what’s continuing to happen [in the Middle East],” Cohen said.

photo courtesy of Kim Kyne Cohen

Another artist whose work contended with the war was Lisa Kokin, based in El Sobrante, California, who showcased a stitched fiber piece called Red Line. “A red line is defined as the line beyond which it’s not okay to go,” Kokin said. By stitching with red, Kokin expressed her feeling that many red lines had been crossed in the Middle East.

While the exhibit opened avenues for dialogue, it also highlighted the limits of dialogue in contentious times. After being accepted, seven artists chose to withdraw their work when the museum did not meet a list of written demands—including calling for a ceasefire, divesting from all corporations associated with Israel and more. In what would have been their place, the museum left a blank wall and a placard explaining why the wall was blank. “At a time when many may need connection,” the placard wrote, “the blank walls speak to a moment when connection may also feel insufficient or impossible.” Ultimately, the exhibition and its controversy were reported on by the New York Times, the San Francisco Chronicle and other news sources.

Inbal Shalev, Director of Youth Programs at Jewish Family Children’s Services, believed the museum did allow for the display of varying perspectives. “It was a safer place for political art to be displayed,” she said. Out of the six or so times she visited, Shalev grew a fond appreciation for the museum’s gift shop; in a favorite memory, she and her husband came across a menorah from an Israeli designer whom they recognized.

For teens in the museum’s internship program, the California Jewish Open was a final opportunity to engage with contemporary Jewish art before the building closed to the public. One of those teens was Zola Ortiz de Montellano, a current junior whose favorite piece was a family dinner table that viewers could sit at. However, this was not any table: “You were able to feel a heartbeat,” Montellano explained.

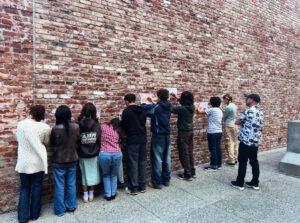

Like Montellano, Lauren Thompson ’27—another teen intern and LWHS sophomore—was disappointed to hear the program’s final meeting would be in February. “Being able to bond with the group of interns has been really nice,” Thompson said. Over the course of the internship, teens met with local artists including Robin L. Bernstein, Ramekon O’Arwisters and Amy Trachtenberg. Her favorite moment, however, was helping to lead a workshop that recreated stolen World War Two art.

photo courtesy of Lauren Thompson

Going forward, the CJM plans to post digital content with the hope of reopening in 2026. However, many are worried about the potential of losing an in person, cultural space. “Art can’t truly be appreciated over the Internet,” Cohen said. “You can get a taste of it, but you can’t feel it in your body.”

In times of heartbreak and division, the role of cultural institutions becomes more important than ever. Heading into 2025, Bay Area Jews—and their allies—are faced with both a loss and an opportunity to come back more united.