The Lick-Wilmerding statistics classes have been collecting observational data about alcohol use at the school for the past three years. Data from two Lick- Wilmerding surveys suggests that no strong correlation between self- reported alcohol consumption and self-reported GPA exists.

While GPA doesn’t necessarily reflect true learning, understanding, or commitment to school, GPA was used as a quantifiable variable in the studies to abstract academic performance and facilitate comparison between students. The study did not take into account other documented consequences of drinking — such as the potential toll on social-emotional well being, risk for alcoholism, nor the well- documented long term danger of prolonged alcohol consumption. According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), “even over the short time frame of adolescence, drinking alcohol can harm the liver, bones, endocrine system, and brain, and interfere with growth.” Furthermore, “young people who reported beginning to drink at age 14 or younger also were four times more likely to report meeting the criteria for alcohol dependence at some point in their lives than were those who began drinking after age 21. Although it is possible that early alcohol use may be a marker for those who are at risk for alcohol disorders, an important question is whether early alcohol exposure may alter neurodevelopment in a way that increases risk of later abuse.”

The data from two surveys — administered in the fall of 2012 and in the Spring of 2014 — were collected by Honors Statistics classes to track a wide variety of quantifiers of alcohol use for the classes of 2015, 2017, and 2018. Both surveys were observational — association can be concluded from them but not causation. For causation to be inferred (or possible), an experimental study must be carried out, where treatment or processes are randomly assigned to participants. For various reasons, including the illegality and unethicality of asking students to consume alcohol, experimental studies were not carried out. The 2012 survey polled the full school, while the 2014 survey had 326 responses. Neither survey controlled for potential reporting errors — in particular students either inflating their self-reported GPA, or either under or overexaggerating drinking frequency or amount. When compared to actual grade quintile distribution provided by the college counseling department in the school profile, the self-reported scores were approximately aligned with the actual distribution, suggesting that students were accurate in self-reporting their GPA (which is encouraging news for the accuracy of other self-reported data). While no clear bias can be assumed for drinking, an argument could be made for students increasing drinking frequency or amount because they conflate drinking with social status or “coolness” (hopefully not), or students decreasing drinking frequency out of awareness that anonymized groups of results would be shared with the administration. In addition, the multiple choice questions the students answered left plenty of room for interpretation by the responders. Two students could respond to the question “When did you first consume alcohol?” with “at 13 years old” — but one student might have seriously consumed hard liquor at a party at 13, while the other may be referencing consumption of a small amount of communion wine with their parent’s sanction.

The data was analyzed this year by seniors Quinn Donohue ‘16, Alex Sahai ‘16, Maya Levin ‘16, Miles Jones ‘16 and Anthony Sinclair ‘16 for a project in their Honors Statistics class. The study tracked frequency of drinking in students across grades, the age at which a student first consumed alcohol, and the way that students perceive drinking as affecting their own GPA and the GPA of their peers, as well as the actual comparison of students’ grades who drank. “We wanted to explore the relationship between alcohol and GPA, both how drinking actually affected GPA, and how students perceived the effect. We also wanted to see if the presumptions of Lick-Wilmerding students matched the data we analyzed,” Levin explained.

The data reveals that older Lick-Wilmerding students self-reported consuming or having consumed alcohol at a rate higher than the averages found in nationwide studies. A comparison between the two reveal a fair gap between the data in each, though not all of the data are statistically significant. The CDC’s 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System estimates that 55.6% of ninth graders nationally have consumed alcohol before, whereas at Lick, 60% of ninth graders self-reported drinking, which is not statistically significant because it could have happened randomly 17% of the time (p-value of .17). For 12th graders, on the other hand, 75.6% of twelth graders nationwide have consumed alcohol compared to 93% self-reporting at Lick — a statistically significant difference in drinking habits (p-value of <.0001). On top of this, a 2014 Foundation for Advancing Alcohol Responsibility study shows that 37% of twelth graders and 24% of tenth graders have drunk alcohol in the last 30 days, whereas at Lick 64% of twelth graders and 43% of tenth graders self-reported drinking alcohol in that time period. An examination of more recent Lick-Wilmerding data shows a similar trend: in a survey conducted last year, 54% of the class of 2018 (then freshman) and 93% of the class of 2015 (then seniors) reported having consumed alcohol before. This data is extremely close to the previous years of Lick-Wilmerding data, suggesting consistency in self-reported drinking rates across years. This data is also interesting as it shows freshman reporting having consumed alcohol at a rate extremely close to the national average for their grade, while the seniors were reporting having consumed alcohol at a rate far higher than their respective average. While approximately 45% of high schoolers nationwide who had not consumed alcohol as freshman had consumed alcohol by the time they reached senior year, that rate was 61% at Lick-Wilmerding.

The major goal of the study was to examine the academic performance of those consuming alcohol, in this case measured through GPA. An examination of the data reveals there is little to no correlation between the amount a Lick student said they consumed alcohol (p-value of .84) and that student’s GPA. Again, the data were from an observational study, so no causation can be assumed, but the group found no statistically significant difference between the age a student said they first consumed alcohol and later GPA (p-value of .01) nor frequency of later drinking (p-value of .63), suggesting that students’ GPA and later drinking habits are not affected by when they began drinking. There was also little correlation between the first time a student said they drank and the frequency that they say they drink alcohol now (p-value of .63).

Though these results might seem counterintuitive (or perhaps that Lick students are simply more skilled at maintaining higher GPAs while drinking), but these data actually line up well with results found by national studies. A 2012 National Center for Biotechnology Information (part of the U.S. National Library of Medicine, a government agency) study attempted to measure the effects of high school drinking on GPA. To do this, they surveyed a large number of high school students regarding their drinking habits, and then collected those students’ GPAs from the school. The conclusion of the study was that there was no statistically significant correlation between drinking and lower GPAs for females and for males a statistically significant decrease of GPA by .07 for every hundred drinks consumed in a month. A Center for Substance Abuse Treatment study conducted in 1994 found that students who drank heavily enough for it to be considered a drinking problem were far more likely to drop out of school, develop mental health issues, and attempt suicide.

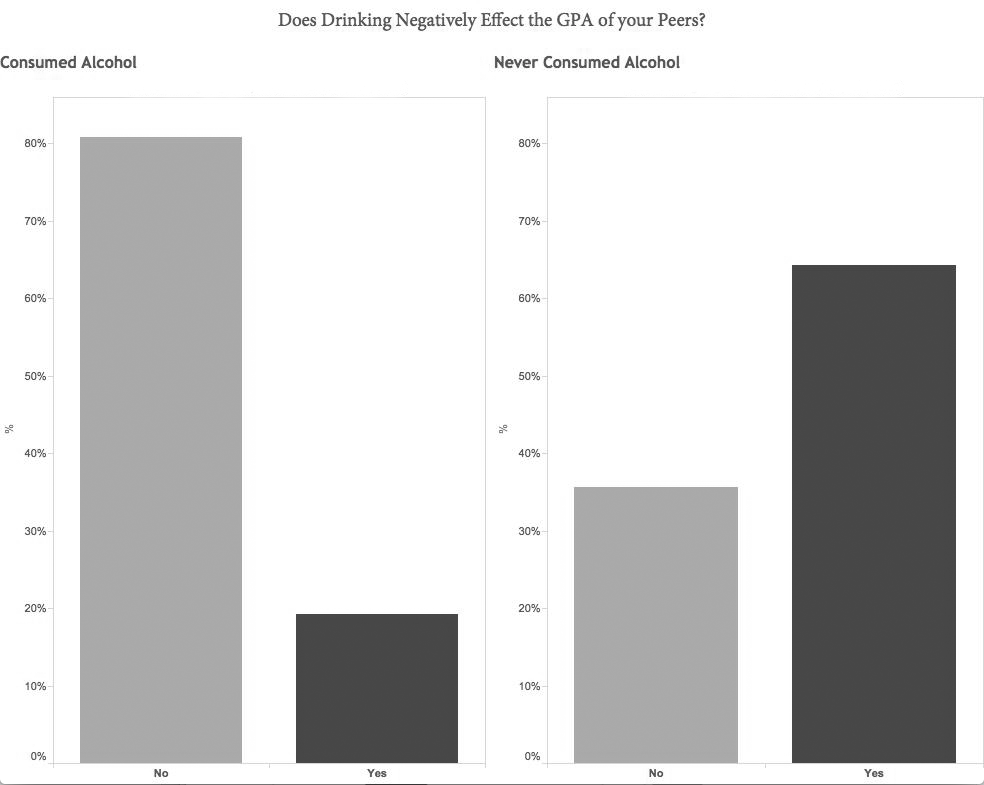

Student self-assessment of the effect drinking has on GPA aligns with these findings. Of Lick-Wilmerding students who self-reported that they consumed alcohol, 87% believed that drinking did not negatively impact their GPA. Out of the larger population, including students that had never drunk alcohol, 67% believed drinking didn’t affect the GPA of their peers. However, when those who drink and non-drinkers are separated, an even larger divide opens. 80% of those who have consumed alcohol believe drinking doesn’t have a negative effect on their peers’ GPA (much closer in line with the 87% who believe personal GPA isn’t effected), while 64% of those who have not drunk alcohol believe it does negatively impact their peers’ GPA. This difference was statistically significant (p-value of .0001), but since those who drink greatly outnumber non-drinkers in the sample, the aggregate sample is skewed towards no effect on GPA. One sophomore, who requested anonymity, said in an interview with the Paper Tiger that they believed that “it definitely has an impact on students GPA, you’ll have a lower GPA if you do drugs and alcohol, because from what I know about drugs like weed, it impacts your neurotransmitters and can mess up your brain growing to its potential, and alcohol impairs your judgement for long time.” One senior, who also requested to remain anonymous, felt differently. They said that “In my experience, drinking has not negatively impacted my grades, in fact as I’ve started drinking more my grades have improved — I don’t think there’s any causation, but as I’ve matured, and as I’ve become more confident and more social, I’ve also started doing better in school, but I’ve also started drinking more as I’ve been going to situations where drinking happens.”

Data were also collected on Lick student’s perspectives of their alcohol usage relative to their peers. Students were asked to compare themselves to how much they felt they drank compared to the average Lick student. Nearly 50% of the students who responded said they believed they drink “much less” than the majority of their peers. Though these data do not show anything about how much the students actually drank, as there was not a definitive baseline the students were comparing themselves to, it does show that at least half of the students at Lick feel that they drink far less than the average student at Lick.

Though Lick students do tend to say they drink alcohol more than the national average, the overall evidence suggests that there is no strong link between the first time a person drinks, if that person drinks regularly, and that person’s GPA. Though the study was not able to find a connection between drinking and GPA, it did help to reveal aspects of the drinking culture present at Lick-Wilmerding: from the many students who turned from non-drinkers to drinkers during their time at Lick, to the large portion of drinkers at the school who feel that drinking will never affect their GPA, to the disproportionate number of individuals who felt they drank far below the average. Though this study and national studies do not show a strong correlation between alcohol consumption and GPA, it is important to note that GPA is not the overall measure of a person’s well-being and should not be treated as such. Though the amount a person drinks might not affect their GPA, studies still show that it can have many other negative effects on a person’s life.

Hmmm … if I am correctly understanding the data presented in this article, it appears that 9th graders at Lick are no more likely to drink alcohol than 9th graders at any other school. However, the longer a student is enrolled at Lick the more likely they are to drink significantly more than students at other schools ? That’s a frighten thought ! Is it possible to work your data in reverse ? Rather than ask if alcohol consumption negatively impacts GPA, perhaps you can check to see if high GPA’s correlate with higher alcohol consumption ? Or if educational communities focused on achieving high GPA’s correlates with higher alcohol consumption by students ?