photo by Gabe Castro-Root

In recent weeks, acts of racism at local San Francisco parochial and independent schools have been in the spotlight. At the Drew School, students of color expressed outrage after incidents of blackface and usage of the N-word were inadequately addressed by the school’s administration. At Sacred Heart Cathedral Preparatory, no immediate action was taken by the administration to discipline a student who posted a racist song that threatened gun violence against students of color.

Lick may seem well-guarded from these events, as its website explains that “LWHS builds a community that embraces the experiences of students from all backgrounds.” However, many students of color do not feel fully embraced.

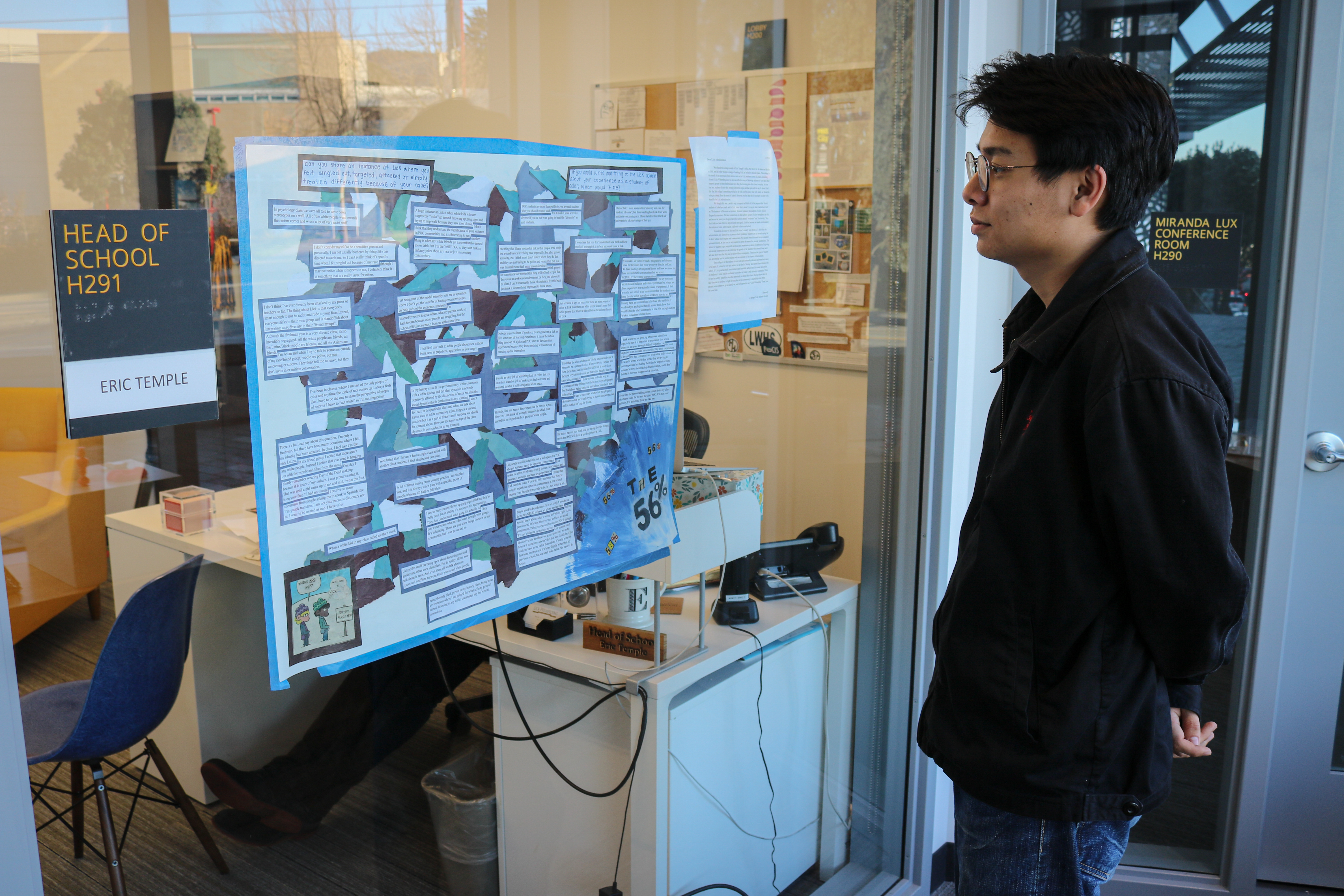

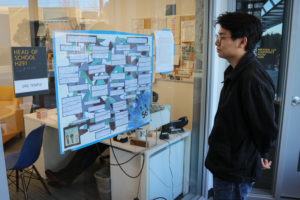

A few weeks ago, an anonymous group of students of color placed a poster and letter in front of Head of School Eric Temple’s office. The poster was a collage comprised of anonymous quotes from students. They expressed how they felt that the administration did not care about them, racism was not properly addressed, promises of diversity and equity were left unfulfilled and that there were inadequate methods to provide feedback to the school.

One of the anonymous students (anonymous student 1) who created the poster and letter explained that issues brought up by students of color are often acknowledged, but administrators “don’t take direct measures to make [students of color] feel safe in the community.”

Another anonymous student (anonymous student 2) explained that students of color were “not taken completely seriously” in previous efforts when they voiced problems that needed to be addressed.

The physical poster, which could not be ignored, was an effort to ensure that students of color would not be left unheard again.

The comments mentioned in the poster and the thoughts of the anonymous students were in line with what Director of Student Inclusion Naomi Fierro has been hearing from students since she started at Lick this year. She explained, “students feel unheard” and when immoral and unethical behavior occurs, there are no clear consequences or “acknowledgement of the harm being caused.”

When Temple read over the poster and saw the negative experiences of students of color, it was painful and hurtful for him to know that students were having these experiences, but he was also encouraged by their desire to speak out about it. He said, “every time we’re asked to reflect on who we are and how we are serving our students, it’s good for our school.”

English teacher Michecia Jones was saddened, not because the poster was a surprise, but because “[the school was] having this conversation again. It definitely feels like we have this conversation every year in some form or fashion.” Jones further explained, “it’s hurtful and annoying to be still looking at the dilemma.”

Jones said she thinks that very little change has occurred because there is “fear on behalf of how students may react if certain action were taken and fear of how parents will react to that, especially because they’re paying.” Jones said that this fear causes distress and people are afraid to take action whether or not it is the right thing to do.

School administrators responded to the poster in a letter addressed to all students and parents. The letter, titled “Our Imperfect Union,” summarized the main messages of the poster and letter and cited specific goals the administration had to address the issues brought up.

These goals included finalizing language guidelines—the usage of slurs and epithets—for in-class texts and in informal school spaces, clarifying consequences when derogatory language is used, creating affinity space forums for students to share feedback, and committing to authentic conversations about the strengths and challenges of diversity.

The creators of the poster and letter were satisfied by the school’s response. The administration listed “real, hardcore examples of what they’re actually going to do and that’s not something that we’ve seen before,” said anonymous student 1. Now, the group of anonymous students is waiting to see if the administration acts on their promises.

This is not the first time that Temple has encountered these concerns from students. He has heard the same sentiments for over thirty years, both during his nine years at Lick and at other private institutions he’s worked at.

Temple cites Lick’s structure as a private school as one of the principal challenges. Over 60% of Lick students pay full tuition and more than 80% of applicants are rejected each year. “The expectation is that we should be a completely equitable, democratic school and yet, by definition, we are not,” he said.

Jones echoed this concern, explaining that “[Lick] is a private school and we are diverse and we are moving in the direction of progress. At the end of the day, however, this is a private school and there is a particular history behind that.”

Another problem is the language Lick uses when pitching the school to prospective students. One of the common themes mentioned in the poster was that the diversity and equity that Lick promised did not match the student of color experience. Temple has met with the admissions staff to change the language used when addressing prospective students. He hopes to communicate that though Lick is diverse and committed to creating an equitable environment, the school is not exempt from history and the world.

However, this isn’t to say that Lick has not taken steps to improve the student and faculty of color experience.

In the past five years, Lick created new faculty positions: Dean of Adult Equity and Inclusion and Director of Student Inclusion. These roles were created to, respectively, recruit and retain faculty and staff of color and create a safe environment for students where they feel heard and welcomed by the school community.

There is now a Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Committee on the Board of Trustees and a Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Roundtable comprised of the Head of School, Director of Student Inclusion, Dean of Adult Equity and Inclusion and members from the Board of Trustees, Parent Association and student body. These groups work to communicate about equity and inclusion in the wider school community and how different groups on campus (parents, faculty and students) view Lick’s successes and needed improvements. This ensures that all groups on campus feel heard and represented and allows for more effective, hands-on collaboration.

In the past decade, the school’s student of color population has increased by a significant amount. This achievement stems from Lick’s goal, as Assistant Head of School Randy Barnett explained, to build a critical mass where students see that there are others who share their identity. This is essential especially in intense conversations and discussions where it can be threatening to be consistently singled out.

Student diversity plays an important role in classrooms. When a class is more diverse, Jones said, the mood is completely different. The environment is typically “more authentic, usually louder, usually more relaxed, and none of those things preclude the fact that learning is actually happening.” Diversity also helps students recognize that they can be themselves in the classroom. This often makes it easier for students to take in the content being taught.

The goal of building a critical mass also applies to the faculty and staff. Barnett wants potential employees to look around and see that Lick is a place where there are people like them. In the past ten years, the number of faculty and staff of color has nearly doubled. Now that the student body is over 50% students of color, Barnett explained, “students want to see the same relative backgrounds and experiences expressed in the adults who teach them.”

To reach this goal, the hiring committee, composed of Barnett, Dean of Adult Equity and Inclusion Tamisha Williams and the Director of Human Resources Anne Condren, attended a cultural competency in hiring training and a workshop on diversity in hiring. These training sessions and workshops informed Lick’s current hiring process.

Before meeting possible employees, the hiring committee discusses the biases they may have towards people who attended a prestigious school, with white-sounding names or certain core identifiers. The main focus of this exercise is to ensure that when filtering through job applications, the committee is only looking for people with the best qualifications and experiences.

During interviews for prospective faculty members, the committee makes sure they craft proper questions that determine whether or not a candidate has the experience to cultivate the culturally-aware and inclusive environment that Lick strives to achieve. For example, they wouldn’t ask what diversity meant to a potential employee. They would instead ask what specific experiences the potential employee had working with students of color. “Their experiences will show us that they have that commitment,” Barnett said.

The hiring committee also considers the demographic makeup of the department that the potential employee is applying to be a part of. A common question that Barnett addresses during the hiring process is, “What identities are we missing that would serve our students well?” If a candidate meets the qualifications and experiences needed for the role, the committee does their best to get them into the final pool of applicants.

When Jones applied to work at Lick four years ago, there were no black women teachers in the English department. Since then, the number of black women on faculty and staff has substantially increased — Jones said, “I feel personally way more supported than I have in other jobs in terms of diversity, specifically my demographic.”

After hiring employees, the focus shifts to retaining and adjusting them to the Lick environment and culture. There are people of color, LGBTQ+ and white, anti-racist (called Disrupting White Supremacy) adult groups. These groups build camaraderie by going out to dinner together and sometimes have program-directed activities. For example, the Disrupting White Supremacy group has discussed articles about white fragility and how to unite against racism. Barnett said, “[the group] digs down and discusses [these topics] in conjunction with our own practice.”

There is also an optional mentor-buddy program for new employees. Mentors are volunteers from the faculty and staff and receive small stipends for the time spent with their “buddy.” They can, like the adult groups, go out to meals together. This serves to bring new employees into the Lick culture and foster a more direct sense of connection among FacStaff.

When a new faculty or staff member is of a minority group, Barnett said, he “connect[s] them with somebody who works in the school who shares that identity.” New employees can better adjust to the new work environment and receive advice from those who may have previously had similar experiences to them in the workplace.

Once the school year starts, teachers visit each others’ classrooms. For new teachers, this gives them a sense of what is expected of a Lick teacher and what a Lick-Wilmerding education looks like. It is also an opportunity for teachers to learn how to enforce and use inclusive practices. This may involve how to check in with group work and handle dominating students. This also gives teachers an opportunity to receive feedback from more experienced faculty. This procedure, titled the Critical Reflection Process, was standardized three years ago.

Teachers’ strengths and weaknesses are also indirectly evaluated through the LWHS Standards for Teaching and the school’s equity pedagogy. When it comes to the equity standards and pedagogy, Barnett explained, “[teachers] embrace it or [they] don’t work here.” The standards for teaching revolve around four main sections: life-long learning, professionalism, commitment to equity and adaptability and flexibility.

The commitment to equity aspect of the Standards of Teaching says that teachers should maintain high standards for all of their students, assess students on what they’ve been explicitly told to learn and differentiate their instruction depending on students’ personal experiences. The equity pedagogy is similar, but highlights the importance of collaboration, interdisciplinary learning, performance-based assessments and connecting the outside world to class material.

After teachers are evaluated on the standards of teaching and equity pedagogy and receive feedback from the Student Experience Survey, they form goals and methods of reaching them. This may involve reading books embodying cultural awareness or attending professional development opportunities such as conferences, workshops and trainings.

For example, after two faculty and staff members said the N-word in a white affinity space two years ago, there was training for advisors and teachers on how to navigate difficult conversations with students and colleagues.

“[Lick has] a very robust professional development budget” to support the faculty and staff, Williams said. The reasoning behind this is to ensure that adults remain educated and aware so that they are not “going to do on to [their] own students the same thing that [they are] asking them not to do to other people.”

Every year, Lick sends teachers and students to the National Association of Independent Schools’ People of Color Conference (PoCC) and the White Privilege Conference (WPC).

According to the PoCC website, the conference “equips educators at every level, from teachers to trustees, with knowledge, skills, and experiences to improve and enhance the interracial, interethnic, and intercultural climate in their schools.”

Lick works to achieve these same goals in the classroom. Barnett explained that one of the main ways that Lick works towards this is by leveling the playing field. Students who attend Lick come from independent, parochial, public, and charter schools from around the Bay Area. The main question that Barnett considers is, “How do we assess students on what we are teaching them and not what they bring in?” This means that teachers need to be explicit about the learning objectives in their class and have clear rubrics to ensure that no bias is present and that the teacher knows exactly what they’re looking for when grading.

Since the anonymous student poster was put up, these goals have become even more important. Jones explained that the topics covered in the poster resonated with many teachers’ pedagogy and incited personal reflection in the FacStaff community.

Jones said, “more than a handful of other teachers are thinking about how to make equitable decisions in their classrooms.”

For Jones, equitable decisions mean considering what curriculum is covered in the classroom (ensuring that students feel represented in the material) and how it is taught.

However, Barnett explained, “[Lick is] not perfect and it never will be. People will always struggle in different ways.”

“This school gives many students and families access to colleges and to a job market they may not have access to otherwise,” said Barnett. “But there can be a cost for that access…They can encounter racist behavior from ignorant people or from well-meaning people who are ignorant and that’s painful.”

In Jones’ experience, racism happens in classrooms on an “imperceptible level,” often through pontification. Pontification is when a student acts as if they are well-versed or very familiar with material being learned in class. This may shut down others who don’t understand what’s going on in class or have questions about the material. From observation, Jones notes that when students pontificate, it’s a “balance between white males and white female students, but it’s not limited to them either.”

As Lick works to solve its problems, Jones encourages students to continue speaking up and reporting incidents of racism to trusted adults in the community. That way, Jones said, “it’s going to continue to make it harder and harder to ignore.” Fierro echoed these hopes, saying, “it’s not the students’ job alone to make changes, but I also know that students are really critical in getting adults to move and take action.”