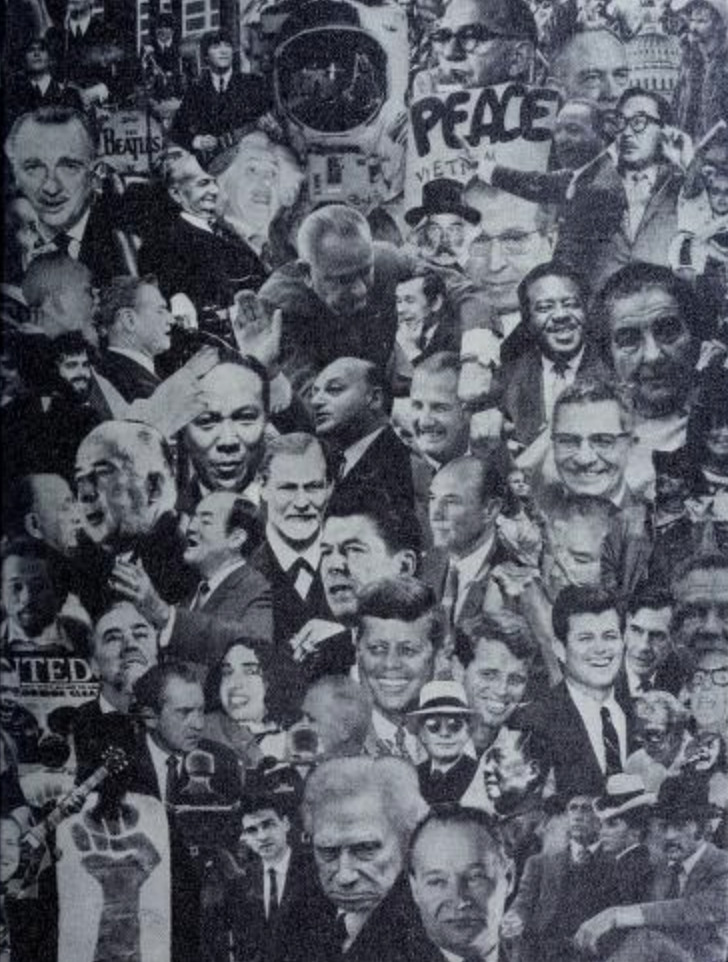

The social unrest in America that exploded in the late 1960s had long been festering. The successes of Black Americans and of women during World War II empowered and emboldened oppressed groups to demand change. The white dominated clture and white male privilege of the U.S. was increasingly under attack. A corps of brilliant young lawyers attacked racist laws. In 1948, President Truman mandated the integration of the Armed Forces. 1954, the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v Board of Educationn paved the way for the integration of school. This decision marks the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement. During the War, women had also experienced new roles. They escaped the confines of their homes and “feminine” occupations and became essential workers in the war effort. Postwar questioning of the prewar status quo of American society became a new norm. The intellectual world was aswarm with new powerful voices invoking change.

For example, in 1963, James Baldwin published The Fire Next Time, Martin Luther King, Jr. “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Pauli Murray “The Negro Women in the Quest for for Equality,” Betty Freidan The Feminine Mystique The Vietnam War, Maurice Sendak Where the WIld Things Are, and Donald Sobal published the first of his Encyclopedia Brown children’s books.

The Vietnam War, officially between North and South Vietnam, had begun in 1955. By the mid-1960s the U.S. was deeply involved, throwing its massive military engine in support of the South Vietnamese government. Along with the Civil Rights Movement, the Student Free Speech Movement and the anti-Vietnam War Movement became the pivotal forces of the decade.

Counter reaction to these movements initatied further social conflict.

For example, more and more Americans began questioning a faraway war mostly impacting the civilian population of Vietnam, a growing peace movement blossomed in the United States. Anti-war protests began on college campuses. The movement captured America and stirred chaos and civic conflict. Men evaded the draft and there were mass anti-war demonstrations. Peaceful protests were often brutally put down. Peace supporters were villainized. This was a time of upheaval and great tension. The chaos unleashed a wave of assassinations of political figures.

Many young adults found the world around them contrasting greatly with the views and opinions they may have grown up with.

Students at LWHS too were impacted by the dysphoria of the times, caught between the structured, conservative optimism of the post-World War II years of their childhood and the fracturing of the mask of an allegedly heroic country.

Tim Erickson ’71 explained his experience with the place many LWHS students found themselves in: “There was a giant counterculture movement, as well as the anti-war movement…We grew up playing heroic WWII games, that’s the kind of thing we all played as smaller kids. Now we were growing into adolescents trying to think about what was really going on.”

Robert Sanborn ’69 said, “Many of our parents were very strong pro-war people. My dad put decals and American flags on our car, our VW bus, a very hippie vehicle.”

Stephan Haggard ’69 said, “The thing that I remember about Lick more than anything else was that it was an intensely intellectual environment. With a growing sense of social inequality and greater conscience about racial issues and injustices, it was also a time that people were reading a lot, thinking a lot, and developing criticisms”

Besides internal conflict, students faced an emotional reckoning with the tumultuous world. Sanborn continued, “It was a very disturbing time for those of us in high school. I found it to be disturbing and it was in the news on a daily basis. Who knew how long this war would last” Who would have known, especially students, that the war would go on for years, ending in 1975?”

Erickson explained his experiences with campus activity. Referencing the infamous Free Speech Movement; months-long student-led protests at UC Berkeley over rights to free speech in academic freedom in the mid-1960s, he said, “In LWHS specifically, we had a speaker series. They would come to speak to us in the library and I remember one really well. I believe he was a very high-ranking officer in the local national guard and he was talking about the national guard’s plans for containing riots in Berkeley. He talked about tanks and armored vehicles in Oakland, and how serious national guard troops could be brought into Berkeley to quell the riots.”

Sanborn said, “There was also a huge demonstration against the politics of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968, mostly around the Vietnam war. It became a riot, lots of people were injured and the mayor called out riot police. My father’s relatives lived in Northern Michigan and I was on a plane to visit them. The plane stopped in Chicago, and the flight became full of about-to-be protesters.”

Though protests and demonstration participation varied from student to student, interviewees reflected on how the entire LWHS community felt the omnipresent war. Seniors were often only months away from their eighteenth birthday, and with it came the dread of the draft. War conversations happened anywhere, from within the school community to the dinner table. The LWHS environment was not oblivious to the world around it. As Sanborn elaborated, even faculty were well-known to be politically engaged.

Haggard said, “We had a Latin teacher that was very involved in anti-war efforts. I remember one time I saw her at an anti-war protest, it was quite jarring, seeing a faculty there.” Haggar elaborated on another teacher and said, “There was a teacher by the name of Jack Coffee. He was incredibly literate — he taught fiction and English — and his classes were always very dynamic. There was an intellectual environment, and at the same time we frequently didn’t know what we were talking about, but a lot of times our judgment was more correct than those in power.”

“I remember in my junior year I took a trig class and our math teacher’s name was Sarah Chrome. She would often not be in school on Monday morning because she would go to a Vietnam anti-war protest. She was frequently arrested at these demonstrations. In her case, I guess the Alameda County sheriff’s jail would occasionally keep her overnight and she was not present in class, because she was engaged in protest,” said Sanborn. “The civil rights movement was very profound at that time as well, and it was in full progress at this time. That was also an awakening, one became aware of a reality that perhaps we weren’t aware of,” he explained.

Reflecting on the role LWHS played in his worldview as a student, Haggard reflected. “Lick was an environment of critical thinking, and more than anything, that is what I appreciated about the place. I can’t say I was a particularly astute thinker and we were all in the process of learning. But that was definitely something that was encouraged,” he said.