This October, Tunisia held open, democratic presidential elections for the second time in the country’s history, nearly nine years after the Tunisian Revolution kicked off the pro-democracy movement known as the Arab Spring.

Though voter turnout was only around 55%—comparable to that of the United States in the 2016 election—voter registration has steadily increased in the country. Since local elections were held last year, the number of registered voters in Tunisia has risen by nearly two and a half million, up to almost 70% of the country’s eleven million people.

“It is important to express our will by voting,” said Jamel Ben Saidane, a tour guide for foreign visitors in Tunis, the capital. “Nobody can ignore the will of Tunisians anymore.”

Tunisians elected Kaïs Saïed, a conservative former constitutional law professor who has never held political office, as president. The October 13th vote was a runoff between Saïed, an independent, and Nabil Karoui, a media mogul and another newcomer to politics. In keeping with political trends around the world, both Saïed and Karoui emerged as outsiders who advanced to the runoff election after defeating candidates from mainstream parties.

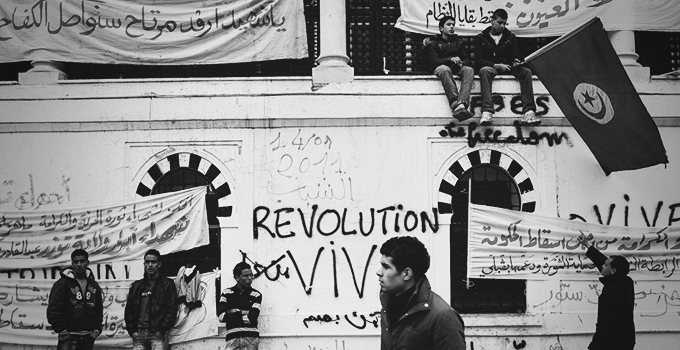

The movement for democracy in Tunisia began in late 2010, when a street vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire to protest government corruption. Bouazizi’s self-immolation quickly became a symbol for the hardship and repression faced by many Tunisians under the authoritarian rule of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, who had been in power since 1987.

Less than a month of popular protests forced Ben Ali to resign, and a transitional government was tasked with creating the world’s newest democracy. The revolution was “an experience between hope for a better future and fear of the unknown,” said Ben Saidane, age 34. Ultimately, “we were relieved from a nightmare that lasted for 23 years.” Tunisia held its first democratic presidential election in 2014.

Tunisia’s democratic transformation came partially as a result of the mass mobilization of young people who demanded economic opportunities, civil liberties, and above all, free elections. “The revolution and all political movements that happened after and continue to happen now have been and will always be carried by the youth,” Ben Saidane said.

Olfa Mohamed, a women’s rights activist in Tunis and a member of the left-wing Democratic Patriots’ Unified Party, said that youth are continuing to play a crucial role in shaping the future of Tunisian democracy. “Young people have a very strong political and civic conscience,” she said. “The real achievement of this revolution is that marginalized youth and marginalized regions have learned not to be silent anymore.”

Mohamed, who was in her early 20’s during the revolution, frequently participated in demonstrations against Ben Ali’s totalitarian rule. “Despite the fact that my parents were very scared for me, I never let go of protesting against poverty, unemployment, corruption and police repression,” she said.

Women have been vocal political leaders in Tunisia since well before the revolution. Many of the strikes and protests that swept Tunisia in the early 2000’s were organized by women, and a powerful network of female “cyber activists” have continued to stir popular unrest online. In 2014, “the strong mobilization of women led to the election of liberal economic political forces,” Mohamed said.

Mohamed poses in front of a mural during the revolution in 2011. She holds a sign in Arabic that reads, “Resistance until the fall of the regime.”

Photo courtesy of Olfa Mohamed

“What is now happening in Tunisia is watched by all in the Arab world,” wrote Mohammed Bamyeh, a Jordanian professor of religious studies at the University of Pittsburgh, in 2011. As Tunisians have transitioned to democracy, people and governments of other Arab nations have continued to closely monitor how events in the country have unfolded.

Nael Khader, a translator and journalist in Morocco who is originally from the Gaza Strip in Palestine, said that Palestinians “are hailing the Tunisians and are so happy with the experience that Tunisia is having.” When Ben Ali was overthrown, people across the Middle East and North Africa “celebrated with the Tunisians, regardless of political orientation. Everybody was celebrating what was going on in Tunisia,” he said.

Mohamed said she was not surprised that Tunisia transitioned to democracy before other Arab countries. “Tunisia was the first Arab country to abolish slavery in 1846, the first Arab country to have established a constitution in 1861, the first Arab country to abolish polygamy in 1956. Tunisia has pioneered in the field of education and been a pioneer in the field of promoting the status of women, and therefore, true to this avant-garde position, Tunisia is the first Arab country to have overthrown a dictatorship, thanks to the will of its people,” she said.

Tunisia is the only Arab country with a democracy, and one of only two democracies in the entire Middle East and North Africa region. The other, Israel, has been paralyzed by razor-thin margins in two elections this year, and no candidate there has been able to gain the support needed from parliament to form a governing coalition.

In Egypt, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has been met with protests over corruption allegations and new policies that give him greater control over the government. “The guy literally changed the constitution to stay in power,” Khader said. “The constitution! That does not happen in Tunisia.”

But, for all its successes, Tunisia’s democratic processes are still far from secure. “Democracy no longer plays its role of achieving more social justice and better economic growth,” Mohamed said. This has led to “a great crisis of confidence,” leading a small but vocal group of Tunsians to call for a return to dictatorship.

Khader, who coordinated Twitter campaigns with activists from Tunisia’s left-wing political coalition Popular Front during the revolution, also expressed concerns about how far the country must still go to solidify the strength of its democracy. “I wouldn’t even say it’s an adolescent,” Khader joked about Tunisian democracy. “The democratic transformation is still a baby in Tunisia.” He worried that “international intervention” by financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and USAID would corrupt the democratic process. “Who has the money has the say,” he said.

In spite of these challenges, Ben Saidane believed that “Tunisians are determined to work more and harder” to sustain their democracy.

Now that the government is no longer run by the same leaders indefinitely, Khader explained that both politicians and the voting public have been forced to change how they think about government decision-making. Politicians “have to do their best for the people, and if they don’t, they only have four years,” he said. If the people are unhappy, “we will have another election and vote for someone else. But at the end of the day, if democracy brings anyone to power, we should trust the process.”