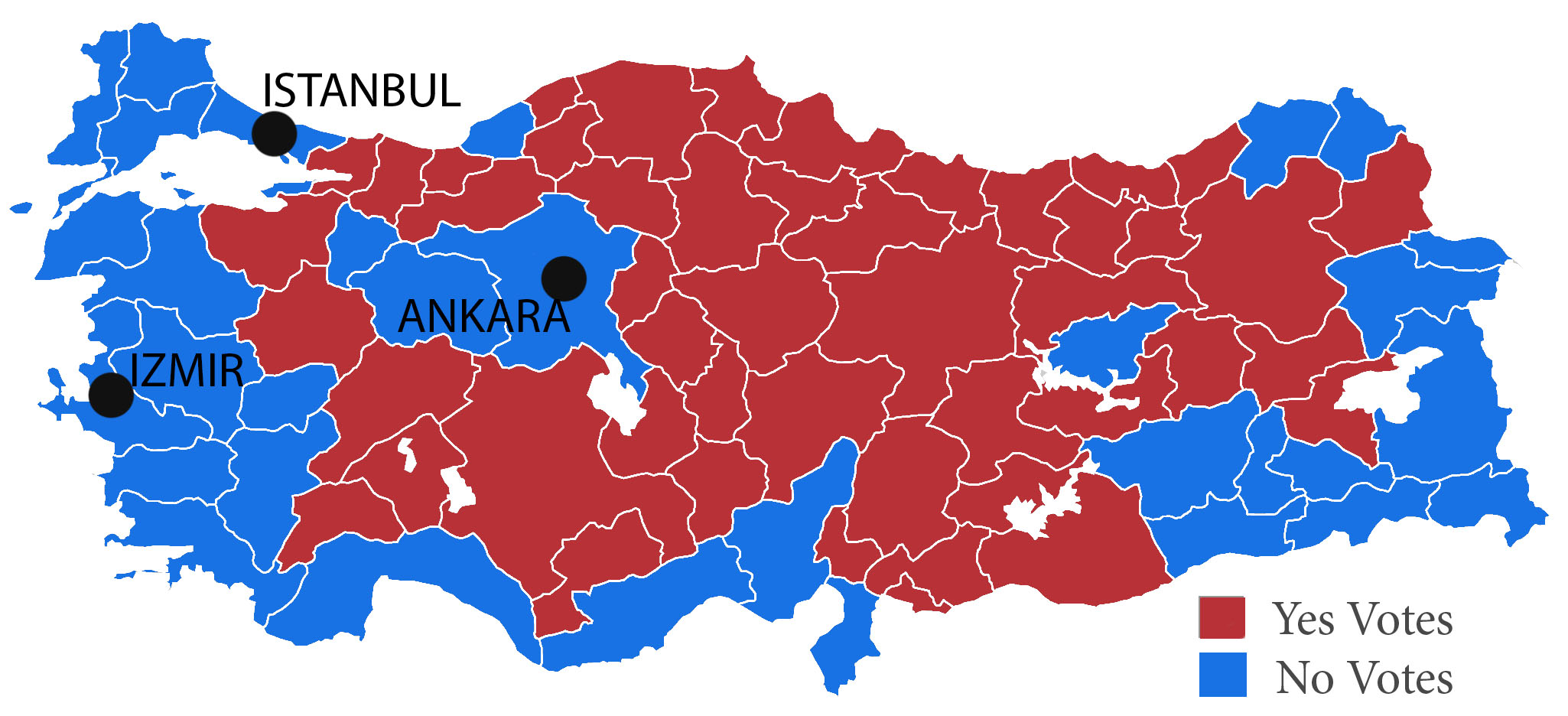

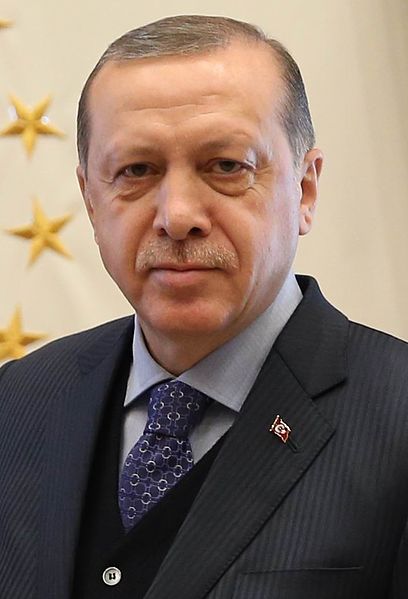

On April 7th, 2017 Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (pronounced “Erdowan”) was given broad constitutionally assured powers in a tight 51-49 vote on a contentious referendum. The vote was split across rural/urban lines, and the referendum was seen by many as a survey on Erdoğan’s support in Turkey. Among other things, it will eventually shift Turkey from a Parliamentary System of Government to a Presidential system more similar to the United States.

The “No” votes on the referendum were centered around cities and coastal areas, so much of Erdoğan’s support came from primarily rural, non-coastal areas.

International monitors were quick to criticize what they saw as an “unlevel playing field” where media coverage was strongly biased towards the “Yes” side of the referendum. Since the failed coup last summer, Erdoğan has initiated an assault on the press, and this disparity in coverage was due to him. According to Human Rights Watch, “over 160 media outlets and publishing houses closed down since July 2016” and “over 120 journalists and media workers [are] currently jailed pending trial” while more than “100,000 civil servants have been summarily dismissed or suspended without due process and over 47,000 people have been jailed pending trial.”

Additionally, there were questionable vote counting practices. Roughly 1.5 million votes were submitted in envelopes which did not contain the official stamp. The issue of unofficial votes has been debated as a coincidental problem in the voting process, or a purposeful cheat of the system. In order to allow for those unofficial votes to be counted, the electoral commission (YSK) passed a new rule allowing for envelopes not bearing their official seal designed to combat fraud to be accepted unless they were proven forgeries.

Western news organizations criticize the referendum as a poorly disguised power grab because it formally abolishes the position of Prime Minister and gives Erdoğan much unchecked power as president. The Turkish Prime Minister is traditionally the leader of the country, while the president takes a more sideline role, but Erdoğan has led the country as its president since he invoked a state of emergency following a failed coup attempt last summer. While Erdoğan has maintained this position of power throughout most of the past year, the referendum’s success makes him far and away the the most powerful man in the country.

One of the more worrying statutes of the referendum is one that grants Erdoğan the ability to unilaterally appoint and remove the judges who rule on his policies. In the vague phrasing of the new constitution, Turkey’s President (Erdoğan) can “issue decrees relating to matters of executive power in the name of the parliament” and even more vaguely the president is allowed to “determine national security policies and to take necessary measures.” Similar to the United States, however, Erdoğan can now formally associate with a political party in parliament. The new constitution states that the president is limited to two five year terms; however, they may serve an additional third term if their second term is shortened due to an early parliamentary election.

While international press jumped to criticize the referendum, the reaction among the Turkish rural population was jubilant. Turkey is known as a melting pot where western ideas dominate politics, but close to 98% of the population is registered as Muslim. Despite the overwhelming majority, Turkey’s politics have been dictated by a more secular elite since the founding of the country (as we know it) in the aftermath of World War I. Erdogan originally ran for office as a Muslim secularist, and has since received a mixture of both criticism and support for expressing his desire to Islamize Turkish politics. Erdoğan has always been open about his ambitions, and he is well known for having said, “Democracy is like a streetcar. You ride it until you arrive at your destination and then you step off,” but his aspirations become more consequential now that he holds almost supreme power.

Recent instability within Turkey gave Erdoğan the opportunity to consolidate his power. The country has accepted over three million refugees, and it is in constant fear of terrorist attacks. Turkey is also struggling with a rebellious Kurdish sect, and its proximity to embattled countries such as Syria and Iraq has also proven problematic. Especially as the Kurds seek their own independence while they fight in Syria and Iraq in the US-led coalition against ISIS. Kurdistan was briefly independent immediately following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire after WWI, however their population was divided between Turkey, Iraq and Syria soon after the father of modern turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk forced a revised treaty. Kurds make up roughly 17% of modern day Turkey’s population, and have chafed against the ruling government since they were forcibly integrated in 1923. The Kurds also seek to revive their own state, which historically spanned throughout parts of Turkey, Iraq and Syria

Turkey’s problems are further exacerbated by an economic slowdown. GDP growth was 9% in 2011, but by 2014 it had shrunk to 4.5%. Turkey recovered well immediately following the recession, but it has suffered from a slowdown in exports to and from Europe. The influx of refugees also contributed to slowed economic activity.

Turkey is an important US and western ally. The country has proven to be an integral member of NATO, and it is viewed internationally as the most prominent external factor in the Syrian civil war. However, its perceived descent into undemocratic government has harmed the possibility of it joining or creating trade deals with the EU and the West as a whole. Turkey is positioned as an important bridge between Europe and Asia, and accordingly a noncooperative government would be disastrous for relations with the Middle East. This is especially true of the refugee crisis; in a TIME Person of the Year shortlist, author Jared Maslin declared that “The European Union has all but outsourced its refugee crisis to Erdoğan and, with it, the future of Europe’s own elected leaders, if not the E.U. itself.” The EU and Turkey are heavily interlinked, so the future hangs in balance as Erdoğan commands his country with a clearly consolidated grip on power.