Though San Francisco is a largely progressive city, it certainly is not exempt from the racial issues plaguing contemporary America. These problems are especially apparent in many Bay Area high schools as students struggle to understand the role race and racial identity play in their lives. Marley Pierce, Lick-Wilmerding’s Center for Civic Engagement Program Manager, says at Lick, “[similar to the rest of the world,] racial issues are being pushed to the forefront. But it’s important to be aware that these issues have always been present for students of color.”

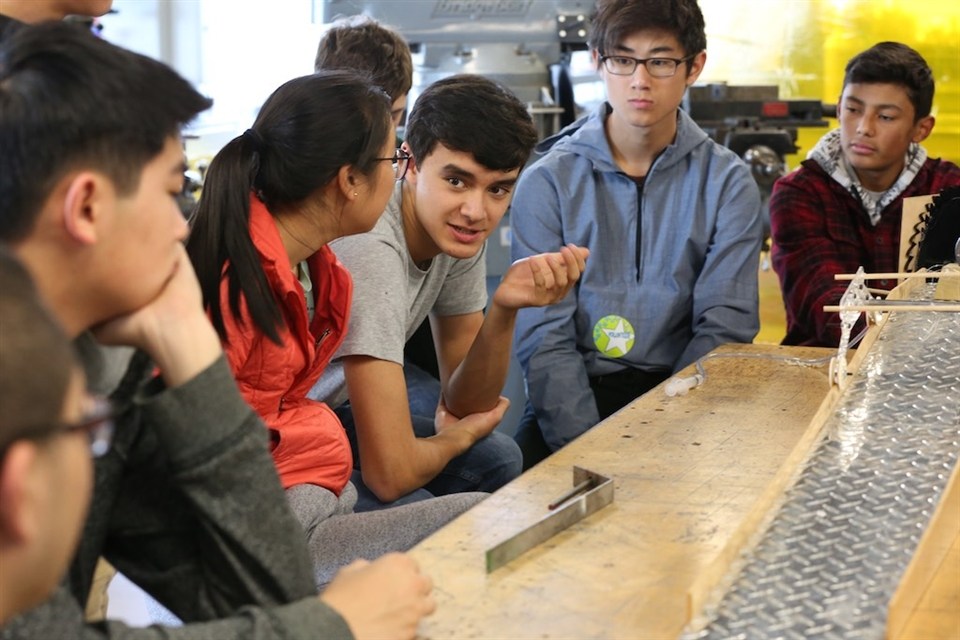

photo by Ryan Fernando

Dr. Rebecca Hong, chair of the history department and a history teacher at Lick-Wilmerding, says, “Race often divides us, but also can help us identify with each other and can bring us together. These divisions and allegiances show up in how we engage in certain academic subjects, with school in general, with sports, and with the arts. How we associate ourselves in schools at both the student and adult level is therefore always deeply imbued

with racial histories.” Hong acknowledges the tension between students open to discussing race and those who aren’t. “Some students are very resistant to talk about race, I think because it raises so much intergroup anxiety, and because people are raised with different levels of comfort around discussing race. Other students crave more conversations about race that go deeper than the dialogue we currently have.”

Alan Wesson, the Public Purpose Program Director at Lick-Wilmerding, says “Racial issues have become more of a public conversation, a conversation that has recently been going on schoolwide although adults have been expressing concerns for a while.” He also addresses diversity at Lick, an issue which is discussed often within the community. “Diversity is often seen as a ‘selling point,’ but there is a lot more diversity here when you compare Lick to other high schools.” He added, “Race is a big part of how students express themselves socially, and the Center [for Civic Engagement, where many students hang out,] is a more diverse space. There is some automatic labeling that happens here, making assumptions based on skin color, that can come from both white students and students of color.”

Though Lick generally attempts to prioritize issues regarding race, the situation at other Bay Area high schools varies. Conversations about race seem imperative for students, but it is still an uncomfortable topic for many and thus the discussion is never started. Tiffany Hue ‘18, a student at St. Ignatius College Preparatory, says, “Diversity is present, but it isn’t embraced. For some reason, race is a sensitive topic. Yes, people support other minorities here. But when you ask them about race, they’ll act like they don’t even know what it is.”

A faculty member at Sacred Heart Cathedral Preparatory, who chose to remain anonymous, says, “‘Race’ does not affect our school community as much as other schools outside of San Francisco. We live in a bubble because San Francisco is one of the most unique cities in the world.” They emphasized the matter of perspective when comparing San Francisco to other cities in the United States. “I think it is important for us to realize that it is very different outside of San Francisco and the rest of the United States. We are lucky to live in a city that is so ‘racially’ diverse.”

photo by Ryan Fernando

The faculty member chooses to put words pertaining to race in quotes because they view race as nothing more than a social construct. “To be straightforward,” they say, “‘race’ is simply not real. We, as humans, are more genetically the same than, for example, two fruit flies or two penguins that look almost identical. America uses ‘race’ as a way to put people into categories based on the color of [their] skin when in reality we are more [alike] than we think.”

A student from Sacred Heart Cathedral says, “[Recent events, such as the 2016 “Wigga Party”] have made many students who weren’t aware [about racial issues] before aware now and very much prepared to help others understand that racism is still a problem today, regardless of the bubble that we live in here in San Francisco.” As a person of color, they feel that, “We are somewhat held to a higher standard to educate our peers. We are expected to be able to handle these certain situations and speak out on them.”

From a quantitative perspective, Lick-Wilmerding, Sacred Heart Cathedral, and many other San Francisco high schools are diverse; many of these institutions see over 50% of the student body identifying as people of color.

However, a common concern amongst students is that while the student body itself is racially diverse, oftentimes members of affinity groups choose not to interact with people of different ethnic backgrounds.

For example, another student at Sacred Heart Cathedral had a different perspective on the school’s community than the other student and faculty member interviewed. Speaking under the condition of anonymity, they say, “Race impacts cliques and the people we hang out with at school.” They expand on this by saying that white students often tend to form groups together while African American and Hispanic students assimilate amongst themselves. According to them, students of different ethnicities rarely intermingle. Speaking of the school’s Asian population, they say, “Everyone seems to think that Asians are different and should be treated as such. There’s even a certain area of the school designated [by students] as the ‘Asian corner.’”

Racial division by friend groups seems to be a prevalent theme throughout several San Francisco High Schools. Grecia Sambrano ‘18, a student at Lick-Wilmerding, commented on how race has affected where and who she hangs out with at school, particularly in the Center. “The Center is seen as a space where the community of color hangs out, and it forms our friend groups. There are some friend groups that are mainly white, and there are other groups that are mainly people of color… The Center and the people who work here want this space to be more comfortable for us kids of color and to be a safe space.” The goal of the Center is to provide a space for all students. Although the Center wasn’t created specifically for students of color, it has become a place for them, as well as others, to gather and study. Sambrano adds, “But I think that’s not the way to go. Why do we have to go to a certain place to feel comfortable? I feel like sometimes the school goes at it wrong. I want to feel safe everywhere.”

photo by Ryan Fernando

“Race is a major factor that sets us [students of color] apart from everyone else because almost everyone here is white,” Hue comments about St. Ignatius. “Because we are a different race, it feels like we don’t get to be friends with them. We can talk with them, but we don’t hang out with them, we don’t go out to eat with them, and we especially don’t party with them. The social community at SI is really cliquey. If you’re [not white], it’s literally impossible to get to that more popular status.

“Our race, culture, and background are all a part of our identity,” she continues. “It doesn’t define who we are, but it helps make us who we are. This school is predominantly made up of white students or legacies, and they will judge us for our race and background. I speak as an Asian-American, but I’m sure African-Americans, Latinos, and other people of color can relate to this: we’re afraid that our social status is lower.”

Anna Hambrecht ‘18 of the Urban School made similar observations, “I do think race is a dividing factor at Urban. In some cases, friend groups are loosely based on race. In my opinion, diversity is an issue at Urban in that there isn’t much of it. Racial diversity is acknowledged in that there are multiple affinity spaces for students of color, but the apparent apathy towards racial diversity issues by the general population at Urban is most definitely problematic.”

Joe Woldemichael ‘19, a Lick-Wilmerding student, feels like race not only affects who he is friends with, but also what they talk about and how they talk. He says, “I feel like I have to talk through this filter when I’m talking to a person who isn’t of color. I have to be more literate, whereas when I’m talking to a friend I can be more laidback.” Woldemichael also comments on how race affects his relationship with teachers and other faculty members. “For me, as a black person, it’s sometimes hard for me to raise my hand or answer questions because sometimes you don’t know what a teacher expects from you. Maybe they expect less of you because of your race or they expect more of you because you got into this school.”

Like Woldemichael, a Lowell student believes that the school’s environment has subtle messages for students of color, particularly African Americans. “I can’t go one day,” they say, “without someone pointing out something that has to do with me being African American, [like] my hair and my skin tone. This school prides itself on having the smartest students in San Francisco, but when African Americans only represent [around] 2% of the school population, what subliminal message are they trying to send to the African Americans students at Lowell and students trying to apply to Lowell?”

photo by Ryan Fernando

Pierce shared her observations regarding race and diversity at Lick, particularly from the eyes of the students of color she interacts with every day. “Many students will tell you that this school is not racially diverse,” says Pierce. A student’s perception of race, she thinks, is dependent not only on the race they identify with, but their socioeconomic background as well. Sambrano agrees, saying, “Coming from Marin Country Day School, I was one of two Latina girls in our grade. If you were to go to a high school fair and you came from a predominantly white [or private] school, Lick would seem very diverse and would definitely attract students like me. Public schools, however, are so much more diverse, and if a student who went to a public school came here, they’d think it wasn’t diverse.”

Clarke Weatherspoon, Dean of Equity and Inclusion at the Urban School, believes that in the U.S. “Everyone is made hyper aware [of race], yet told not to talk about it.” This is an issue which he feels Urban is not exempt from. “There are times at school where students feel great racial solidarity and also tension around race. Sometimes students employ humor they see online and it falls flat or they misunderstand the boundaries of those around them.” Weatherspoon also acknowledges that the students are just high schoolers. “At times, they engage in profound, mature discourse and at times they snipe at one another on social media… Do students make mistakes or say the wrong things? Yes. Do I feel that our students are motivated by racial animosity? No.” But no matter the context, Weatherspoon considers it the school’s job to ensure that students always “listen to one another and respect the views of others” in order to respect people of many backgrounds.

photo by Ryan Fernanado

Although many schools acknowledge the need for diversity and inclusion, one of the primary challenges they face is starting discussions about race. Often such conversations in high schools are only brought up when triggered by a certain event, and their effects are frequently insignificant. Hue commented on the “Wigga party” last year, attended and organized by students from St. Ignatius and several other Bay Area high schools, that made local headlines. “It was a party where white people tried to act black. [The negative reaction to the party] didn’t change anything; it just made the problem spoken. Before this party, everyone knew what was going on but no one ever said anything about it. But once word about this party got out, it was publicized and we had to acknowledge it. A lot of white people went, and they all got suspended. But even though they suffered those consequences, it didn’t change anything. Their attitudes haven’t changed, and their suspension didn’t drop them to a lower social status. Kids of color were, and are, still on the outside.”

Urban and Lick are both trying to start conversations regarding race during students’ freshman year, but even that strategy presents some problems. At Urban, students are required to take a six-week class called “Identity and Ethnic Studies.” Hambrecht comments on the advantages and disadvantages of the class.“Identity and Ethnic Studies is an amazing class, but there is no class in any other year that continues this important discussion and exploration. If a student wishes to avoid the topic of race altogether after that class, it is 100% possible, which is something that I personally find disappointing.”

Freshmen at Lick have started having class meetings discussing race in relation to the education system as a method to start conversations that can endure to their senior year. Wesson hopes that these conversations will influence how the next four years will play out for them, but recognizes that students have “a lot of competing priorities, like getting into college” that often get in the way of productive and continuous discussions about race and diversity.

Dr. Catherine Fung, an English teacher at Lick-Wilmerding, believes integrating race into the curriculum of all classes is necessary. “I think we need to consider how race informs our entire framework of teaching. For me, I think you’re doing a disservice to understanding American literature and history, and World literature and history, if you don’t deal with the realities of how race has governed our lives and how we represent ourselves. Instead of thinking about teaching race in terms of, ‘This is a unit about race, these are the two weeks we are going to study it, here is the one book we are going to read’ or ‘it’s MLK day and we are going to talk about race today,’ I think it should become a fundamental element of our framework, of just thinking about our world.”

Conversations about racial issues at Lick are still a relatively new concept, which is particularly evident in the school’s senior class. Ami Feng ‘17 and Sophia Yin ‘17, students at Lick and co-presidents of ASIA Club, spoke about their class’ racial divides. Feng comments, “Especially for our class, the administration seems to be very concerned that our friend groups are racially divided.” For Yin, “I feel like, for our class, [conversations about race] weren’t early enough. I think that the affinity leaders and several members of the administration are planning a curriculum for the current freshmen to talk about race. I think it’s good they’re adding that now.”

Moving forward, conversations about racial divisions within high schools will be essential in creating both diverse and integrated communities. Although starting the discussion about race may be uncomfortable, it is the only way to normalize these conversations for students, and hopefully provoke social change. Weatherspoon says, “Understanding differences takes experience. It takes making mistakes, and as a school we are committed to helping people along the way. Teaching [people] to value and respect differences can be a struggle, but it’s a struggle we embrace and hope our students and families do as well.”

Written by Sutter Morris ’18 and Alex Yeh ’18