This fall, Lick-Wilmerding High School hired the first female Head Coach for the Varsity Girls’ Soccer team, Bianca Coad, in several years. Women coaches matter; they challenge gender bias and inspire young girls to imagine themselves in leadership positions.

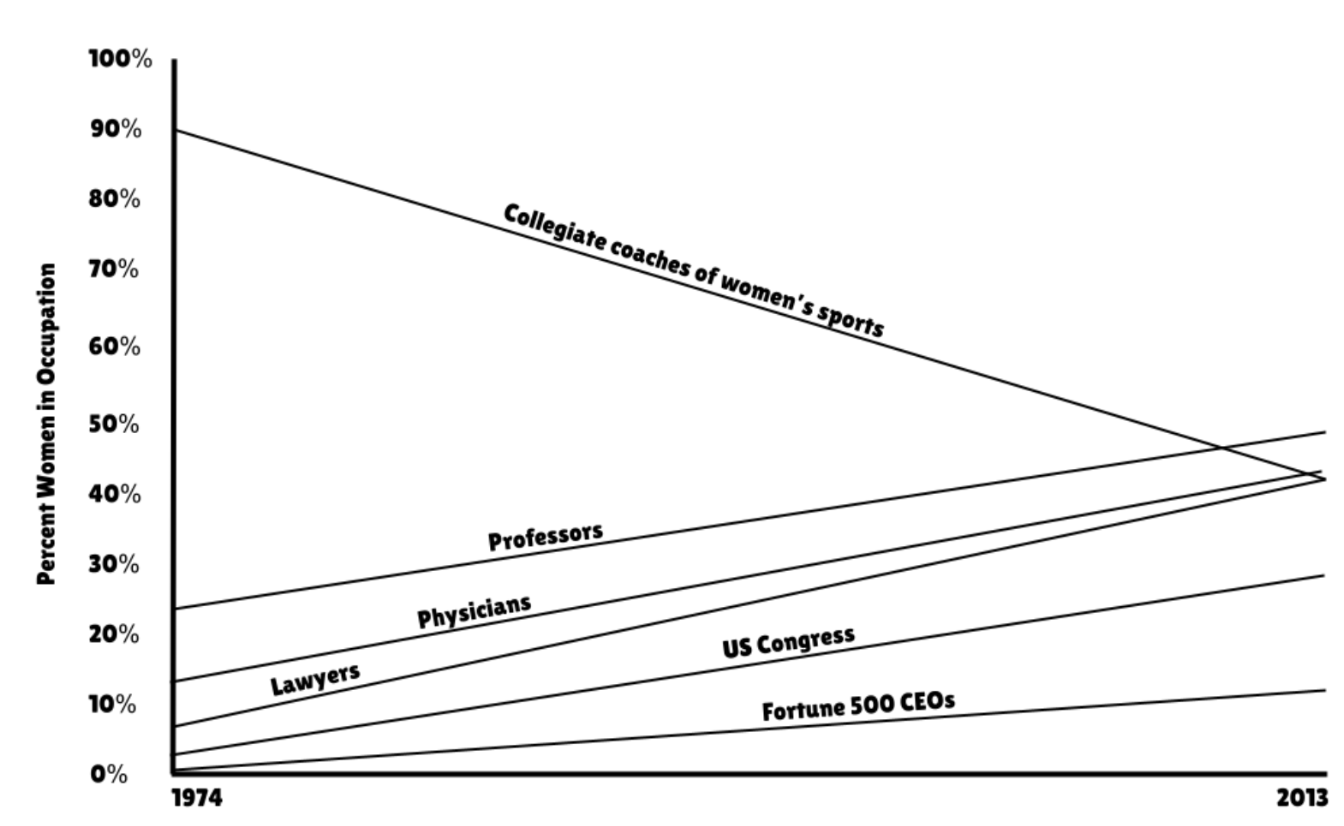

The percentage of women leaders in nearly every sector is on the rise, besides coaching. According to Nicole M. LaVoi, Director of the Tucker Center for Research on Girls & Women in Sport, less than 40% of women’s sports teams are coached by women at the collegiate level. At the youth level, that number drops to 23%. Even more concerning, the percentage of women in coaching positions has been decreasing: just 50 years ago, 90% of collegiate women’s sports coaches were women.

graph by Naomi Taxay with data from “Women in Sport Coaching” by Nicole M. LaVoi

So where did all the female coaches go? One theory is an unintended consequence in the passing of Title IX in 1970, a law that declared equal treatment and funding for girls and boys athletic teams. Title IX was monumental in female athletics. Since its passage, female participation in athletics has risen by 614% at the collegiate level and by 1057% at the high school level.

However, with this extreme increase in participation and funding, more jobs with higher salaries were created in women’s sports. And suddenly, paired with a new status, men were interested in coaching women’s teams.

But there’s more to the scarcity of female coaches than simply the newfound financial incentive for men. Sport is rooted in the gender binary. It’s a place where essential differences between men and women are constructed and maintained.

In addition to athleticism portrayed as a “masculine” trait, so is leadership. “It’s multiple layers of negative stereotypes, that you can’t be a powerful woman who is competitive,” Brain and Behavior teacher Anton Krukowski said.

Kate Wiley, Junior Varsity Girls’ Soccer Coach and Dean of Teaching and Learning, described how female coaches face a different, gendered narrative. “I don’t think women coaches get the same level of respect, that we can train athletes to be competitive, that we train our players to be physical. I think the assumption is that we only train our players to be collaborative, or patient.”

An argument in favor of increasing the number of women in coaching is that they bring unique skills to coaching, like those Wiley described. LaVoi’s Women in Sports Coaching explains that this perspective can actually be detrimental to the cause by reinforcing gender stereotypes and impelling female coaches to endorse them for any chance of professional respect.

Coad believes her job as a youth soccer coach fits into the larger push for women’s equality because it gives her the opportunity to prove that women can do anything men can do and more.

Coad only had one female head coach in her 19 years of playing soccer. She played four years of Division 1 soccer at the University of San Francisco and was captain of her college team, despite coaches telling her she may not be able to achieve her goal.

When men outnumber women in coaching female athletics, many girls grow up only being led by men. In the words of Marian Wright Edelman, Founder and President of the Children’s Defense Fund, “You can’t be what you can’t see.” Without seeing women in positions of power, it’s hard for girls to envision themselves in those positions.

Female coaches are proven to make substantial differences in girls’ lives. Research shows female role models, such as coaches, inspire women to be more ambitious and to aim higher: young girls exposed to female mentorship have a 130% greater likelihood to hold leadership positions in their adult lives.

Wiley began soccer when she was eight years old, coached by her older sister. There weren’t many girls’ teams in San Francisco at the time, and she was pushed to pursue more common “feminine” female-only sports like volleyball as she grew up. Inspired by her sister and her love for soccer, Wiley organized a women’s club team when her high school didn’t have one. She began coaching beside her sister when she was 19, and has been coaching ever since.

“I want my players to recognize that if they self-identify as a woman, there is inherent power, athleticism and physicality in that. And that those aren’t mutually exclusive from also being a thinker, and tactical and strategic. But there’s a lot of deprogramming that has to happen,” Wiley said.

Wiley sees her role as a coach as being about more than creating a winning team. To her, being a coach means being a mentor. She wants her players to develop a love for athleticism that lasts throughout their lives.

Eliot Smith, Director of Athletics, described sports as a mode through which coaches can teach their players life lessons. “I think a great coach is a great teacher. A great coach is trying to teach you winning qualities that will last you for the rest of your life.”

Because of this guiding aspect of coaching, there are reasons girls could benefit from being coached by someone with whom they identify.

“I think a lot about the importance of the role I can play in deprogramming around body image, around food, around the horrible messaging that I think particularly young women are getting around what beauty looks like and what strength looks like,” Wiley said.

“I never had a coach that could relate to my experience as a player,” Coad said. One of the reasons she chose to become a coach was to provide to young women what she never had. She wants to create safe spaces for girls to grow and develop their skills and knowledge of the game.

Wiley herself was coached primarily by men growing up and saw the missed opportunity of what coaching could be. “I often found a lot of my male coaches played with us versus coaching us. And so, to me, it was about their athleticism and prowess and not about us as players.”

“There isn’t an inherent problem with men coaching women,” Alexa DiSabato ’23 said. “There’s just a lot to be said about why so few women are in coaching when female participation in sports is at an all-time high.”

Where Are All the Women Coaches?, a New York Times opinion piece, explains, “We put girls in sports so that they learn the best person wins. We teach them they’re in a meritocracy — until we leave them on their own come adulthood.”

So, although we tell girls their gender has nothing to do with their ability, they might still find their experiences gendered and influenced by sexism when they grow up.

That’s why, according to Krukowski, in addition to pushing for female coaches in women’s sports, it’s equally important for boys to see women in leadership positions.

The number of women coaching men at the collegiate level has remained at 2-3% since the passing of Title IV. If more women coached boys as they grew up, Krukowski commented, they might develop greater respect for women.

According to Smith, the hiring process for both boys’ and girls’ sports coaches at LWHS focuses on an applicant’s experience and ability to educate. Specifically for girls’ sports, Smith said, “my first choice would be for a strong female candidate.”

According to Assistant Athletics Director Spencer Yu ’04, LWHS currently has four female varsity head coaches for girls’ teams. For junior varsity, the school has five female coaches for girls’ teams and two for boys’ teams. LWHS also has six female team coordinators and assistants across all teams.

Smith acknowledged the importance of coaches who understand their players. “Sport is such a big part of our lives in high school. Just having someone you can look up to, that helps with life’s challenges,” he said.

“You don’t remember awards or championships, but what you will always remember is your favorite teacher, your favorite coach,” Smith said. “Someone who made you fall in love with sports.”

Female coaches can introduce female athletes to the beauty of the women’s sports community, according to Wiley. “Until my back injury I was playing three times a week,” she said. “I was playing with women, and they rolled their strollers out if they had babies. People were coming back from breast cancer surgery, from having a hysterectomy.”

There is power to the fact that women continue to play through challenges society sees as weaknesses. By extension, these communities where women are in solidarity with one another can provide solace in a world where they are often pitted against each other.

“The only way we’re gonna get more female coaches out there is if women see this as a part of their lives,” Wiley said. “There is so much beauty in that intersection of the female experience and athleticism. I want that for every player, for all their life.”

melbet промокоды Click Here:👉 http://lynks.ru/geshi/php/?melbet_promokod_pri_registracii_2020.html

Experience the full power of an AI content generator that delivers premium results in seconds. 100% uniqueness,7-day free trial of Pro Plan, No credit card required:). Click Here:👉 https://bit.ly/3Py2Iv6