As the old adage goes, “one man’s trash is another man’s treasure,” and although the gendered language is questionable, the Albany Bulb in Albany, California takes this saying to a whole new level.

Jutting out from the east shore of San Francisco Bay, the “Bulb,” as it is commonly known, is a man-made peninsula and a physical and aesthetic patchwork of human resourcefulness and natural resilience.

Pulling into the parking lot off of Buchanan Street, the Bulb at first doesn’t look to be anything remarkable. The atmosphere is salty, sunny and blustery as one would expect of a bayside attraction. The Albany Beach opens up just in front of the asphalt — dull beige sand-silt wrought with the footprints of windsurfers, paddle boarders and those with enough confidence in their immune system to take a dip in the murky waters of the Bay.

Photo by Gabe Castro-Root

Venturing out onto the narrow neck of the peninsula, Bulb-goers follow a semi-paved dusty road where the sights are limited to the vast bay on either side and the scrappy, scraggly gray-green California coastline shrubbery. Then you reach the Bulb and things start to get interesting.

When the dirt beneath your feet is suddenly coarse gravel and brightly spray painted boulders start to pop up here and there, you know you’ve reached the Bulb.

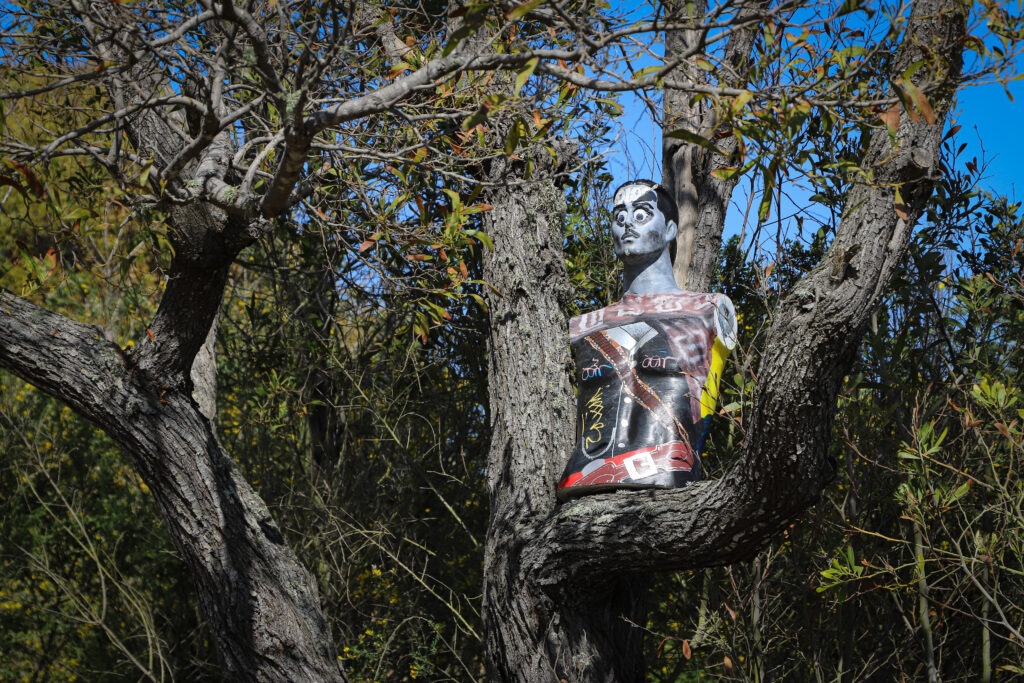

The land is littered with large chunks of debris — concrete slabs, exposed rebar, plaster and huge metal pipes — all covered with surreal vivid colors and designs. Nearly every inch of demolished building and sun-baked stone and metal at the Bulb has served as a canvas for some transient artist. Spray painted murals, graffiti and large stylized words cover all the visible surfaces, in many places layered and layered over decades. Amidst the colorful chaos, chilling statues and sculptures of jagged metal and wood rise up and dot the landscape. The Bulb is a grungy museum of both 2D and 3D art.

Photo by Gabe Castro-Root

The Bulb owes much of its rugged beauty and art to the houseless community that called the Bulb home for many years. In the 1950s the city of Albany joined other communities around the Bay in dumping its deconstruction and construction debris in the shallow waters of the wetlands and tidal margins to create more land for real estate development. Let it be noted, for example, that all of San Francisco’s iconic Embarcadero and Financial District was also constructed on a landfill. After the nonprofit Save the Bay worked to halt dumping in the wetlands and the bay throughout the 60s and 70s, and finally succeeding in the early 80s, the Bulb began to take shape. Free of an increase in debris and relatively isolated from Albany proper, a community of artists and new residents coalesced and transformed the Bulb through spray paint and sculpture.

On and in between these works of art nature has retaliated against the environmental destruction the Bulb’s foundation represents. Though the Bulb rose out of the desecration of nature, the earth has reclaimed its grasp on the small peninsula. Shrubs and grass bloom from the cracks in the discarded stone and wild blackberries (though they are an invasive species) are scattered across the Bulb. At the shore, glistening seaweed and algae coat the coastline stones rounded by the tides. An array of fauna also find shelter at the Bulb –– from seabirds and songbirds, owls and snakes to rats, mice, and black-tailed hare.

Several trails wind through the middle of the Bulb and along the east and west coasts of the peninsula, providing many paths on which to explore the vintage battle between industrialization, marginalization, imagination and nature herself.

Since those days during the heights of “free” space in the pre-gentrification Bay Area, when generator punk parties graced the Bulb’s amphitheater stage, the peninsula served as a periodic base for transient communities. This was until 2013 when the Albany City Council elected to evict all the Bulb’s residents with a monetary incentive.

Once a hub of art and knowledge (old souls who haunted the Bulb in its glory days recall a people’s library where books were left, taken, borrowed and returned freely), the Bulb now only houses cultural vestiges, like Mad Marc’s castle, a structure built from scratch by Madman Marc, a legend of the Bulb, using debris and covered in vibrant murals, and like the “Beseeching Woman,” a haunting sculpture of metal and wood. These, and others, have become fixtures and icons known to the Bulb’s fans and former residents alike.

Photo by Gabe Castro-Root

Though the Bulb is now devoid of all permanent residents but the birds, a few small mammals and reptiles, the trees and beach flora, it occasionally once again becomes a lively venue of human activity. @LovetheBulb on Facebook, with over a thousand followers, hosts semi-regular events for art and performance at the Bulb.

Through a complex past of questionable environmental ethics and human and natural resilience, the Bulb and its hodgepodge of art have weathered storms, droughts, state greed and capitalism. And when you step onto the first painted stones that form a pathway along the coast, you can faintly feel the echos and hear the history in the metal and stone.