Lick-Wilmerding High School, a top-rated private college-preparatory school with rigorous coursework and selective admissions, can sometimes be referred to as a “pressure-cooker” among its students. While the environment provides for an unmatched education and numerous opportunities for life beyond high school, the intensity (both academic and social) can be mentally straining.

But it’s not just LWHS, or even just private schools. High-achieving schools (HAS) are schools with high standardized test scores, rich extracurricular and academic offerings and graduates who go on to study at top colleges — a categorization which many Bay Area schools fall under. Recently, two major national policy reports, the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (2019) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (2018), have declared youth in HAS an “at-risk” group.

Excessive pressures to excel, often in affluent contexts, are listed among the top 4 risk factors for adolescents’ mental health — following exposure to poverty, trauma and discrimination. Youth in HAS have higher rates of serious behavioral and mental problems compared to national norms, placing them in the “at-risk” category just after kids living in foster care, immigrants and children with incarcerated parents.

The stressors are markedly different between these groups, and it may sound illogical or even flagrant to place them in the same category. However, researchers are finding that despite the causes, high levels of chronic stress similarly affect youth’s health and well-being.

One student’s story helps to illustrate the struggles of HAS students and the support services LWHS has to offer. Coco Close ’24 has attended academically intense independent schools their whole life, coming to LWHS in 2019 after nine years at The Hamlin School, “a fast-paced private school very similar to Lick in terms of hustle culture,” according to Close. From a very young age, Close learned how to “survive” in school, getting used to the feeling of being tired every day.

Most HAS broadcast the upsides of achievement — what is much harder to address are the difficulties the factors that fuel high achieving create.

photo courtesy of Vidigami

Relative to national norms, rates of serious withdrawn-depressed symptoms are 3.5-5 times as high within HAS, according to a 2019 American Psychological Association report (conducted pre-pandemic). “In these subcultural contexts, too often, children’s sense of self-worth comes to rest largely on the splendor of their accomplishments, and this can make for both anxiety and depression,” the report states.

Despite the bad mental state Close experienced, which they attributed largely to hustle culture, their acceptance to LWHS fueled their decision to attend and continue their academic career at another HAS. “I had a really hard time with the high school process — I didn’t have a sense of self-worth aside from school. But I was so happy that I was able to attend Lick,” they said.

In HAS, these behaviors reinforce themselves: a student with low self-esteem may look to their grades and/or accomplishments as evidence of their worth. In turn, they are taught to continue achieving in order to be worth something.

Performing well can be a coping mechanism in itself. Often lurking behind perfectionism is the belief that in order to be lovable or worthy, one needs to be perfect.

Close worked extremely hard their freshman year in order to stay on top of their work, but began to fall behind for what seemed like no reason. After being referred to the Learning Strategies Center (LSC) by a teacher who noticed Close’s struggles, they were able to get diagnosed with ADHD, depression and anxiety. “I felt very seen. I felt like things made sense now,” they said. Shortly after, they began to apply for the neurodiversity and mental health resources LWHS offered.

LWHS has a Student Support Services team, composed of administrators, the counselors and the LSC, that is responsible for working with students to identify and provide support for their needs. This can be immediate, such as reaching out to teachers and asking them not to call on a student during a period of crisis, or more long term, such as granting extended time on tests.

Long term accommodations, like those LWHS provides, change how content is accessed and reached. These allow students who are neurodiverse and/or have mental health challenges to still participate in the full LWHS program and meet the school’s expectations.

Long term modifications, which LWHS does not provide, make drastic changes to the content and expectations themselves. A Section 504 plan is one way students can access modifications: because the federal Rehabilitation Act of 1973 prohibits disability (including mental illness) discrimination, students at public schools can individualize aspects of the school to their own plan. Although 504 plans are often difficult to obtain, students with one can receive staggered transition times, permanent extended deadlines on homework assignments, etc.

In public schools, both accommodations and modifications are available: the nuance comes in being an independent HAS, because there is a level of academic standard that modifications would fundamentally alter. LWHS outlines this policy in the Student Handbook.

“On tests, I was able to get the resources Lick offered and that is something I’m really grateful for,” Close said. “But the school does not offer every resource I need, because they try to maintain their rigor. And that’s really disappointing.”

LSC Coordinator Owen Dempsey explained that the Student Support Services team has been constantly examining and solidifying LWHS’ policies, as students are experiencing mental health challenges at unprecedented rates.

Currently, the Student Support Services team is finalizing a standard form doctors can fill out to initiate the process of accessing long term mental health accommodations. While students are encouraged to seek comprehensive neuro/psych evaluations when possible, the process (which can take months and cost up to $10,000) is time consuming and expensive. “We’re trying to come up with policies that make our resources more equitable and accessible,” Dempsey said.

HAS have existed for a long time, however students at these schools are only recently being considered at-risk — and increasingly so every year. The 2019 APA report describes, “As competition for the top schools gets harder, pervasive community norms to work toward ever more achievements intensify.”

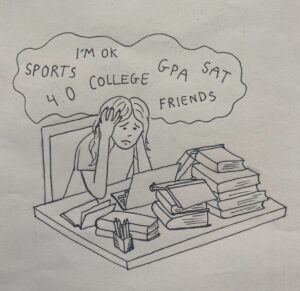

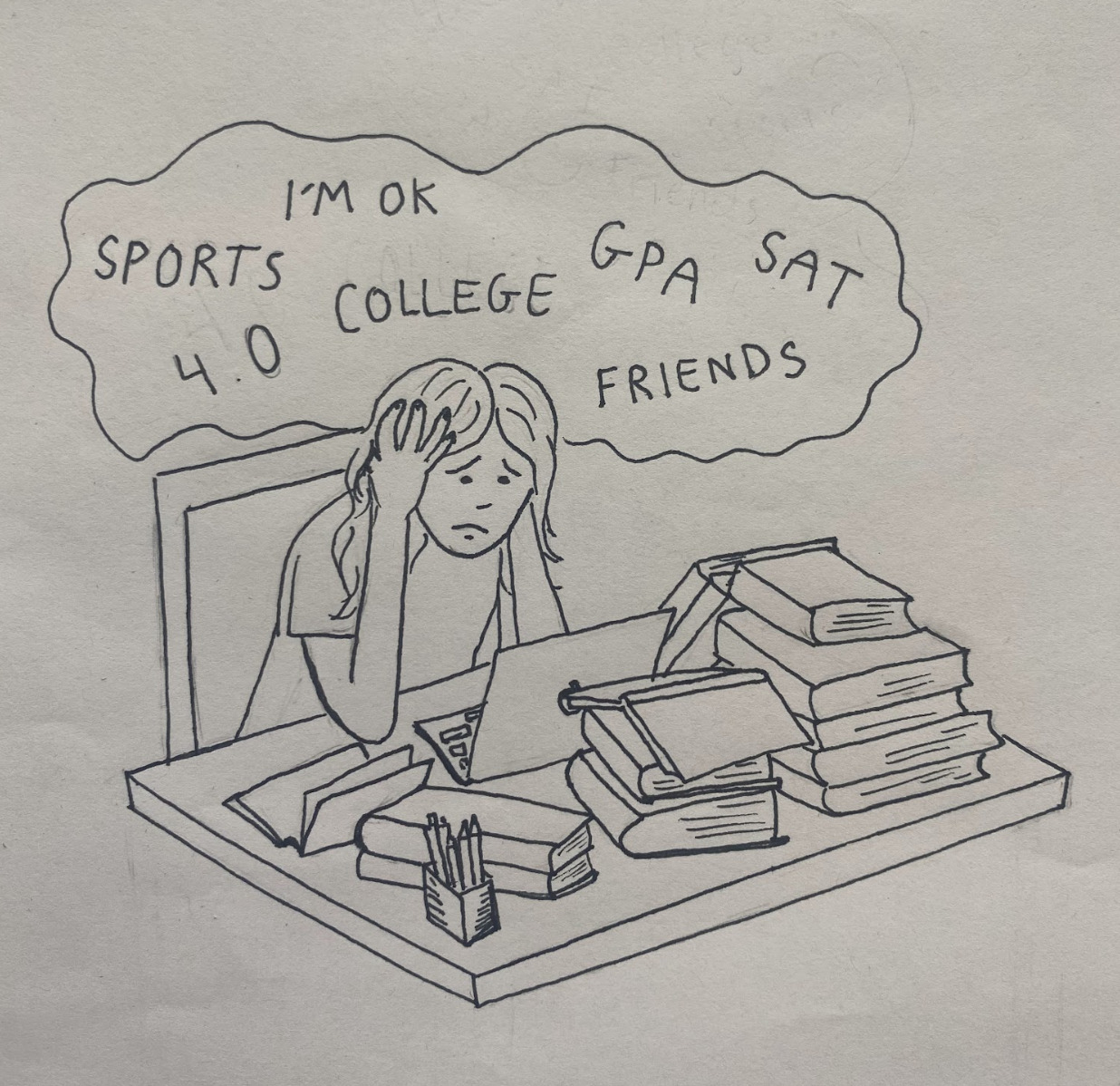

doodle by Charlotte Hahm

These achievements can be academic or even extracurricular. Activities like sports or art, that could replenish students’ well-being, instead become an additional source of stress.

Modern technology is also implicated in the increased vulnerability over time. With the ability to track “odds of getting into colleges” and comparing one’s achievements to others over social media, envy is a major factor in HAS youth’s mental health. HAS students have shown in multiple studies the harmful belief that others’ relative gains implies one’s own relative setback.

College admissions competitiveness has not only increased due to the number of applicants, but also due to the caliber of these applicants. Students today must excel to a level nearly impossible in order to be accepted. This can also translate to parents who, while meaning well, may project their stress for their children’s future onto them.

Junior and Senior Dean Kindra Briggs described the challenge of being beholden to a system and college process that is outside of LWHS. “Lick is focused on making sure that students are excited and engaged in their learning here — yet we also know that each student is looking beyond the walls of Lick into what will happen after,” she said.

Noticing an increase in conversation around the college process and a tendency within HAS to fuel competition, the Student Support Services team has attempted to foster a community of care that focuses on learning and forming relationships. Part of this includes programming for students that prioritizes community and being in the present, such as the Public Purpose Program.

“Research points to the fact that people who are involved in community-oriented spaces and who are committed to service outside of themselves live more fulfilling lives,” Briggs said. “And part of that is perspective — you recognize that there is worth in what you do in the world beyond just a paper or a grade.”

One of the notable aspects of LWHS is the commitment and involvement of its students in the community. Dean of Students Raquel Oliva-Gomez commented that an important part of LWHS’ culture is the freedom of student voice and advocacy — it serves as a way for students to build connections and nourish their spirits, influencing both their own mental health and that of the community.

The Student Support Services team, in addition to helping students navigate their individual mental health journeys, also looks at the larger systems in play when it comes to community mental health. “Our systems are continually being investigated, interrogated and hopefully improved at all levels of the school, from student responses and surveys to conversations that are happening with the support team,” Briggs said.

“We have a responsibility to the mental health of our students. As the center of our community, we are here to steward their growth in all aspects of social-emotional and academic life. So we most assuredly have a responsibility to provide services, resources and support to students,” she said.

Erika Solis, one of the school counselors, echoed the sentiment. “We want students to be able to come here and have an excellent education, and that shouldn’t be at the cost of their mental health. So the Student Support Services team advocates for systemic changes, and we always have an eye on homework and stress level.”

Beginning in January 2022, LWHS implemented “homework-free” weekends, supposedly once a month, in order to give students time to relax and catch up on work. Across the 10 months of the 2022-23 school year, five included a “homework-free” weekend: those that didn’t had at least one long weekend or break.

Olivia-Gomez described the touchpoints LWHS attempts to create with students, from advisory to the nature of the school that encourages student-teacher relationships. “Faculty and teachers can see changes in students (behavioral, academic, social-emotional, etc) if we already have an established relationship with them,” she said.

Dempsey said, “Because Lick is a smaller community, there are more opportunities for connections with the teachers. We also can really work one-on-one with students around getting them the support that they need, and advocating for themselves. I think self-advocacy is something that, in my experience, we’re able to really foster in this environment.”

HAS and universities across the country provide varying levels of care when it comes to their students’ mental health. Yale University, which underwent a lawsuit for systematic discrimination against students with mental health disabilities, is a case that represents the struggles of many HAS students.

It has surfaced that many Yale students have been forced to withdraw from the institution due to their mental health issues. When they are forced to withdraw, or even if they withdraw by choice, they no longer have access to the school’s counseling services and must reapply in order to return.

Because of these policies, many Yale students have avoided seeking help or discussing their mental health issues at all. This has contributed to a high number of unexpected suicides within the university.

Alicia Abramson, one of the plaintiffs of the lawsuit, wrote about her experience in an article for the Cosmopolitan. “The resulting campus culture around mental health is one of fear. It is difficult to describe the hopelessness of desperately needing help but knowing that seeking it might lead to devastating consequences — it’s like you’re drowning, but you know the life jacket might suffocate you too.”

Abramson described an alternate reality where her distress could have been met with a process of identifying suitable accommodations, such as part-time course loads or virtual attendance. Or one where, if she needed to withdraw, she could get support, treatment options, resources and guidance rather than being cut off from the institution.

Close always felt upset at LWHS because of how rigorous it was. They had been taking part in an intensive outpatient program after school in the beginning of junior year, but struggled to get better while juggling school hours and schoolwork. They knew they needed more help but was afraid to seek a higher level of care.

“I was so scared that I was going to get kicked out of the school because I was struggling more. But Lick was so nice. They said, ‘no, your mental health is worth more,’” Close said. “Sometimes I still can’t believe I got that opportunity.”

doodle by Naomi Taxay

Close was cleared to take a medical leave from LWHS and participated in a partial hospitalization program and later a residential treatment center encouraged by the school. “So many things were racing through my mind, but I just felt so grateful and relieved, because I had asked for help and they gave it to me,” Close said.

Close returned to LWHS in the spring of 2022. While they maintained the position that the “grindset” of an HAS is mentally harmful, they feel as though the support they received and the self-advocacy they learned has equipped them to deal with the pressure — and ultimately changed their life.

Attending an HAS such as LWHS is challenging. Some schools ignore, or even attempt to hide, the issues these high-intensity environments magnify. LWHS has the resources, opportunities and spaces for conversation about mental health — however, it is up to students to utilize them and their voices for changes, both individually and institutionally.

“We really want people to ask for help and we really encourage them to ask for help. And we’re here to support them,” Dempsey said. “We care and we want to know how y’all are doing. The door is open, the help is ready. And that starts with asking for help.”

Aviator Play Online https://www.aviator-game-bonus.com/

http://greenpes.com/includes/pages/promokod_melbet_pri_registracii_2020.html промокод на MelBet при регистрации

промокод MelBet https://mebel-3d.ru/libraries/news/?melbet_2020_promokod_dlya_registracii_besplatno.html

актуальный промокод Pokerdom на пополнение https://www.snabco.ru/fw/inc/promokod_pokerdom_oficialnuy_sayt.html

Премиум база для Xrumer https://dseo24.monster/premium-bazy-dlja-xrumer-seo/prodaetsja-novaja-baza-dlja-xrumer-maj-2023/

Лучшая цена и качество.

1xbet промокод на сегодня https://sansk.by/content/pag/promokod__260.html

промокод 1хбет при регистрации на сегодня https://www.home-truths.co.uk/pag/1xbet_promo_code_india_24.html

1xbet промокод https://mac-bundles.com/news/1xbet_promo_code_india_24.html

промокод 1хбет http://newfiz.info/offizika/pgs/promokod__260.html

https://www.astrologysupport.com/wp-content/plugins/lang/1xbet_promo_code_india_24.html 1xbet промокод бонус

1xbet промокод на сегодня https://likitoriya.com/img/pgs/?promokod_259.html

1xbet промокод при регистрации на сегодня https://sansk.by/content/pag/promokod__260.html

http://tdrimspb.ru/news/inc/1hbet_promokod_pri_registracii__bonus_do_32500_rub_.html промокод 1хбет на сегодня

1хбет промокод на сегодня http://photoua.net/images/pgs/promokod__260.html

промокод хбет http://www.newlcn.com/pages/news/promo_kod_1xbet_na_segodnya_pri_registracii.html

рабочий промокод 1xbet на сегодня http://lipetskregionsport.ru/news/pages/1hbet_promokod_na_6500_pri_registracii.html

1xbet промокод при регистрации http://hammill.ru/pages/pgs/besplatnuy_promokod_pri_registracii.html

https://toolsmach.com/img/pgs/promokod_260.html промокод для 1 x bet

1xbet при регистрации промокод https://rg62.info/news/promokod__260.html

1xbet промокод https://illusionweb.org/sxd/pags/promokod__260.html

https://poligon64.ru/pgs/?1hbet_promokod_pri_registracii__bonus_do_32500_rub_.html 1хбет промокод

промокод 1xbet https://kvin-tur.ru/content/pags/besplatnuy_promokod_pri_registracii.html

1xbet промокод https://illusionweb.org/sxd/pags/promokod__260.html

промокод при регистрации 1xbet на сегодня https://van-dekor.ru/img/pgs/?besplatnuy_promokod_pri_registracii.html

промокод 1хбет https://wildlife.by/images/pages/?promokod__260.html

промокод при регистрации 1xbet http://npar.ru/news/1hbet_promokod_pri_registracii__bonus_do_32500_rub_.html

1xbet промокод https://statusexpert.ru/wp-content/art/besplatnuy_promokod_pri_registracii.html

промокод 1xbet при регистрации https://weter-peremen.org/files/pgs/promokod__260.html

1x промокод https://rhoadesdds.com/news/promokod_260.html